Most students at Ohio State are given some kind of warning about academic misconduct. But despite a devoted section on the syllabus and the instructor pointing it out on the first day of classes, some students still cross that line of academic integrity, whether intentionally or not.

Most students at Ohio State are given some kind of warning about academic misconduct. But despite a devoted section on the syllabus and the instructor pointing it out on the first day of classes, some students still cross that line of academic integrity, whether intentionally or not.

And it’s occurring more often.

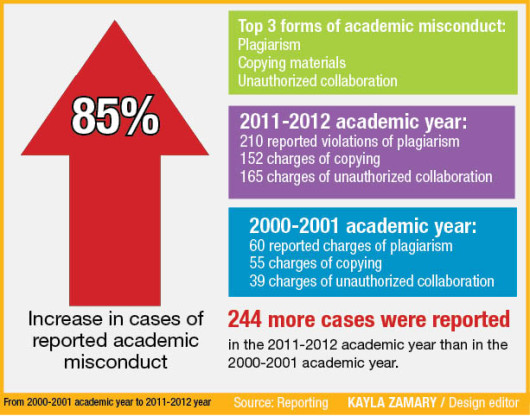

Cases of reported academic misconduct rose by 85 percent from the 2000-2001 academic year to the 2011-2012 year at OSU, according to reports from the Committee on Academic Misconduct.

From the academic year of 2000-2001, there were 287 reported cases, a total that increased to 531 by the academic year of 2011-2012 year. The number of reported cases has increased by an average of 7 percent per year.

Kathryn Corl, the COAM coordinator, said there has been no reason for the increase pinpointed.

“I think it would be misleading to hypothesize why,” Corl said.

Not all those accused were found in violation of academic misconduct – more than 15 percent of those accused during the school years from 2000-2001 to 2011-2012 were found innocent.

The increase of academic misconduct cases, however, is disproportionate to the increase in the university’s total enrollment, which has gone up by about 17.3 percent based on the fall quarters from 2000 and 2011, according to data from the Ohio Board of Regents.

The top three forms of academic misconduct included plagiarism, copying materials and unauthorized collaboration, Corl said.

In the 2011-2012 school year, there were 210 reported violations of plagiarism, 152 charges of copying and 165 charges of unauthorized collaboration. That was an increase from the 2000-2001 academic year, when there were 60 reported charges of plagiarism, 55 charges of copying and 39 charges of unauthorized collaboration.

The rise of the Internet has likely had some influence on students committing academic misconduct, Corl said.

“It makes it so tempting for students to find an essay to cut and paste and assemble,” she said.

Aside from plagiarism, males made up more than half of the academic misconduct cases for each of the academic years on record since the 2002-2003 school year, something that was not detailed in the reports for the 2000-2001 and 2001-2002 academic years.

On average, both rank one and three students each made up less than a quarter of the cases. Rank two students made up about a quarter while rank four students made up almost a third of the cases. The rest were graduate students. The academic years 2009-2010 and 2010-2011, however, did not have the breakdown of total reported cases by class rank.

Corl said since some students come to the university with college credit already the data could be misleading as to why some higher rank students appear more likely to commit academic misconduct.

Some students said those who commit academic misconduct hurt themselves more than anyone else.

“It’s something you shouldn’t practice but if you do it hurts yourself more,” said Loriann Bechie, a fourth-year in welding engineering.

The transition from quarters to semester has impacted the results on the COAM’s annual report for the academic year of 2012-2013, Corl said.

There were 375 cases of academic misconduct during that year, she said.

“We’ll probably start to see some new patterns with semesters,” Corl said.

Corl said in the meantime, there’s a lot of misconception surrounding COAM.

“I want people to understand that the process is designed to support students,” she said. “I don’t believe the police message is effective.”

Both faculty and students can report academic misconduct cases to Corl. As the COAM coordinator, Corl reviews the evidence and decides whether to go forward with the charges.

If the evidence is found to be sufficient, the appropriate student or students and instructor receive a notification of charges.

Corl said she would have a pre-hearing conference with the student or students charged in the case, informing them of the two options to proceed with the charges: a hearing or an admission to academic misconduct.

“It’s the right of every student to have a hearing conducted about the charges,” Corl said.

The hearing consists of a panel of at least four members from the COAM — at least two faculty members and one student who, in the end, determine whether there was a violation, as well as the appropriate sanction if there was.

As for the other option, if the student admits to the charges, then he or she can waive the hearing and let a hearing officer review the case to determine the appropriate sanction.

Some students who are found in violation can receive zero credit for the assignment, face a reduction of their overall grade in the course, receive a failed grade for the course and face possible suspension or expulsion from the university, according to the reports.

Taylor Stepp, Undergraduate Student Government president and a fourth-year in public affairs, said the committee is largely there to guide students.

“The Committee (of Academic Misconduct) is an educational experience, not a punitive one,” he said.

USG is represented on the committee, which is comprised of 18 faculty members, seven graduate students appointed by the Council of Graduate Students and seven undergraduate students appointed by USG, according to the annual COAM reports.

Furthermore, Josh Ahart, vice president of USG and fourth-year in public affairs, said he agreed the committee’s purpose isn’t punishing students.

“I have a lot of trust in the system,” he said, adding that he makes the appointments to the COAM from USG.

Ahart said COAM isn’t made up of only OSU staff and faculty who make the decisions – there are student members who also make decisions objectively.

“I truly believe in shared governance,” he said.

Shared governance allows faculty, staff, students and administrators to have a say in decision-making at universities.

Students can file an appeal if they are found in violation of academic misconduct from the hearing, which involves a decision from the provost.

“The procedures are designed to be fair and considered all aspects,” Corl said. “Its really about academic integrity … (and) that the degree means something.”