“I think you’ll run into this with anyone you talk to who has had an eating disorder: that voice never goes away. There’s always a constant struggle.”

Kelsi Schwall, a second-year graduate student in occupational therapy, started her struggle with an eating disorder at about age 16, and though she’s 23, now with her condition under control, she said it’s still not easy.

National Eating Disorders Awareness Week is from Feb. 23 to March 1, but for students at Ohio State struggling with eating disorders or counselors helping these students, it’s a year-round issue.

Schwall said her busy life in high school and her need for control had a hand in the development of an eating disorder.

“I’ve always been a perfectionist, so I think that was a major part of it. I always tried to push myself really hard in school. I was in way too many things,” she said.

Schwall said it was six months to a year before she got help, and her mom was the one who made sure she received it.

“My mom was probably my biggest supporter through all of it. She knew that there was something wrong, probably just like a mother’s intuition kind of deal,” she said.

Schwall said she tried a variety of different treatments for her eating disorder throughout high school and her time as an undergraduate student at OSU, including participating in individualized therapy at OSU’s Younkin Success Center.

Holly Davis, a senior staff therapist at Younkin whose focus area is eating disorders, said there are “multiple first steps” a student seeking treatment could take.

Davis said individuals on staff take the severity of a student’s concerns, as well as the students’ resources — like their transportation needs and financial status — into consideration when helping assess the best option for each person.

Treatments for eating disorders are covered by OSU’s student health insurance, but the cost of treatment varies on a case-by-case basis, said Dave Isaacs, Student Life spokesman.

However, features such as 10 free counseling sessions available to students per academic year and unlimited group therapy are in place to make sure students can get help, Davis said.

“Ultimately, if a student really needs treatment, they really need treatment, so on a case-by-case basis, we kind of figure it out (in order) to get that student what they need,” Davis said.

One of the services offered at OSU for students seeking help is the Eating Disorder Treatment Team, which is comprised of dietitians, therapists and physicians, Davis said.

“The treatment team is really a place for those providers who potentially have students that they share in serving to come together and make sure we’re all on the same page,” Davis said.

The Body Image and Health Task Force also works to advocate for positive body image at OSU by holding freshmen seminars on body image and health and speaking to students in student organizations like sororities or athletic teams, said Nancy Rudd, professor in fashion and retail studies and chair of the task force.

The task force does outreach all year long but also sponsors the Body Image Bazaar, along with several other departments and organizations, for National Eating Disorders Awareness Week, Rudd said.

This year’s bazaar is slated to take place Monday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. in the lower level of the RPAC. Attendees can expect informational tables, brochures, informational DVDs being played on loop and the chance to take assessments to see the state of their body image or evaluate their eating habits, Rudd said.

The event has grown over the past 16 years, and last year’s event drew more than 600 people, Rudd said.

“It’s very intense visually, a lot information educationally and a lot of opportunities for students and faculty and staff to engage in these self-assessments,” Rudd said.

Along with the formal treatment services, students at OSU who might be struggling with body image, or who simply care about the cause, also have the opportunity to be involved in a student organization, Body Sense, that Schwall started in 2010.

“We teach people that being happy and being healthy isn’t about being a certain size,” said Autumn Blatt, a fourth-year in psychology and president of Body Sense.

Although some members of Body Sense have struggled with eating disorders and the group provides a safe space to talk about those issues, the organization is meant for all students, Schwall said.

“I’ve been trying to recruit people this year by letting them know that sometimes the meetings are just provocative conversations, just kind of criticizing or discussing certain things that are related to (negative body image),” said Zach Thomas, a first-year graduate student in middle childhood education and treasurer of Body Sense.

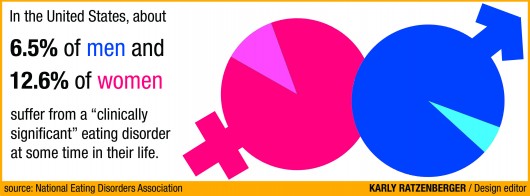

According to the National Eating Disorders Association, about 20 million women and 10 million men in the U.S. suffer from eating disorders at some point in their lives.

“I think we live in a world that talks about obesity and weight gain as these horrible, horrible things,” Davis said. “I do wonder how much of that creates fear in people that ‘if I’m not a particular size, bad things will happen or people won’t like me.’”

Blatt also said society’s focus on obesity is a problem and added that there is not enough conversation about what weight is too low.

“Our society is so geared towards not being overweight, and no one ever gives you a lower extreme,” Blatt said.

Schwall said the stigma of eating disorders is also a problem.

“Eating disorders can be triggered by just a normal diet. You just start taking out less and less, and until you are rail thin, no one says anything, and once you are to that point, now it’s not socially acceptable, and they’re still not going to say anything,” Schwall said.

Eating disorders and negative body image are problems that can start a young age.

According to NEDA, 81 percent of 10-year-olds are afraid of being fat, and more than one-half of teenage girls and about one-third of teenage boys use unhealthy weight control behaviors.

The transition to college can also contribute to poor eating habits.

“You’re on your own (in college), and it’s a whole lot easier to not get caught,” Schwall said. “My parents would call me out. My roommates didn’t know the difference.”

Schwall said college students need to be more educated on the subject, and she said she enjoys informing and assisting others.

This is Schwall’s last semester of graduate school, and she said that is what is keeping her on track with her health.

“I had an eating disorder in undergrad and I’m not going to do that in grad school,” she said. “This is the hardest academic semester of my career, but I’m going to do it.”