‘Italian Peasant,’ painted by Paul-Henri Bourguignon with gouache in 1953.

Credit: Courtesy of Erika Bourguignon

An upcoming exhibition aims to expose the artistic results of the adventurous life of Paul-Henri Bourguignon, whose artworks hung in the galleries at the Columbus Museum of Art (then known as the Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts) in an exhibition precisely 50 years ago.

Bourguignon was born in 1906 in Belgium, and was working as a journalist and photographer in Haiti when he met Erika Eichhorn (now Erika Bourguignon), an anthropologist.

“My husband started painting as a teenager … and began quite early to travel, first outside the city then outside the country,” Erika Bourguignon said. “In the late 20s and 30s, he went to places where there were very few tourists, like Corsica, Bosnia, Spain and North Africa, etc. These were not tourist places and he was interested in not just landscapes, but lifestyles and languages. He liked being in strange and unfamiliar places.”

Erika Bourguignon said her husband’s interest in travel continued on when war in Europe changed his home.

“In 1940 the Germans invaded Belgium, and like all men of military age, he was supposed to go to France and join the French army and the Germans got there ahead of him,” she said. “Then he went back to Belgium, which was very difficult. After the war, he was interested in traveling and went to Haiti, which is where we met.”

The pair later moved to Columbus in 1950 and got married, and Erika Bourguignon began a 40-year tenure at Ohio State, eventually becoming chair of the Department of Anthropology. Yet in the 40 years he lived in the city, Paul-Henri Bourguignon oddly enough never depicted Columbus in his work before he died in 1988.

“The community of artists in Columbus at this time was probably not as vibrant and organized as it is today,” said Dominique Vasseur, CMA’s curator of European art. “I don’t believe artists had as many places to show their work. A lot of his work springs from his travels.”

He was largely inspired by his journeys to places like Spain, Corsica, Bosnia and more generally depicted landscapes, faces and scenes with people in them, Erika Bourguignon said.

The 45 works in the honorary CMA exhibit, “Paul-Henri Bourguignon: A 50th-Anniversary Retrospective,” were drawn from a handful of private collections, but the exhibit’s greatest contributor was Erika Bourguignon, who as of late has been discovering more and more of her late husband’s work, Vasseur said.

Because of Paul-Henri Bourguignon’s newly found art and the 50 years that have elapsed since his last exhibit, the works in the upcoming show are much more representative of his evolution as an artist, both Vasseur and Erika Bourguignon said.

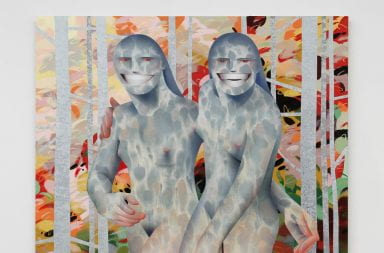

“His works evolve from being much more interested in the representation of the human figure to almost completely abstract work, where it’s very hard to discern a particular subject,” Vasseur said. “He had a real sense of being able to, in a very few lines or brushstrokes, capture a sense of vitality.”

Erika Bourguignon was in Haiti doing fieldwork for her doctoral dissertation when they met, she said. Paul-Henri Bourguignon created many Haitian scenes in bold, bright colors, which symbolizes his powerful memories of his time there.

“We were very much impressed with how poor people were,” Erika said. “In 1947-49, I would say that 90 percent of Haitians were illiterate in any language, there was very little economic base to the society … and there were very few natural resources if anything.”

Erika Bourguignon’s friend and former colleague Richard Yerkes, also an OSU professor in the Department of Anthropology, said Erika Bourguignon has always played a role in getting the word out about Paul-Henri, who didn’t seem to be a big self-promoter.

“I really do regret I didn’t get to know him better,” Yerkes said. “Paul never went out of his way to say much about himself. There are a lot of artists who aren’t as famous as Picasso, but are just as important in the world of art.”

The Bourguignons’ simultaneous work they was linked in more ways than what meets the eye.

“Both of our work had to do with looking beyond your immediate presence to a larger world, and being concerned with how that world operates,” Erika Bourguignon said. “We were both interested in different lifestyles and comparing how people live in various societies, and what problems they share.”

Erika Bourguignon’s work broke many barriers and opened many new perspectives in the fields of anthropological psychology, religion and women, Yerke said, and she directed a five-year project under a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health studying the notions of trance and spirit possession, which are part of Haitian folk religion.

“Erika was always interested in doing something that I think is really hard, and that’s getting at what people really think and believe, and how that influences them,” Yerkes said. “She really was a founder of what we now call psychological anthropology … and I think we sometimes take her influence for granted because we’re so near to her, but people all over the world are aware of her work, and are still learning from what she did.”

The Bourguignons’ impact can still be seen at the university, most notably in the annual Paul H. and Erika Bourguignon Lecture in Art and Anthropology. The lecture was started by Erika Bourguignon and the department, which Yerkes said still relies on her advice, to hold continuing conversation about the strong interconnection between the two disciplines, Erika said.

The next lecture is set for April 2 with speaker Ann Bremner, art historian, previous publications editor for the Wexner Center for the Arts and the author of the CMA exhibit’s catalogue.

Select artworks by Paul-Henri Bourguignon, which range in date from 1924-88, will be unveiled at the CMA on Oct. 17 and are set to be shown through Jan. 18. They represent a vast range of media, including gouache, oil paints, ink and pencil sketches and acrylics.

Much of Paul-Henri Bourguignon’s work continues to be displayed in his wife’s home as she is continually inspired by his art, and there are a number of pieces she would never consider selling, she said.

“Although he passed away in 1988, Paul’s presence is very much alive in this home,” Vasseur wrote in the curator’s statement about his visit to Erika Bourguignon’s home and many of the works now loaned to the museum. “On one wall a strong face might peer forth from darkness, on another landscapes open up views from Haiti, Peru or Europe … while on a table, a group of unmatted drawings looks as if it has just been reviewed.”