OSU Coach Urban Meyer sounds his whistle before the first game of the 2016 season against Bowling Green on Sept. 3 at Ohio Stadium. The Buckeyes won 77-10. Credit: Mason Swires | Assistant Photo Editor

When the Buckeyes beat the Oregon Ducks in the 2015 National Championship game, head coach Urban Meyer hoisted a trophy — and later pocketed $250,000.

For the second time in three seasons, the Ohio State football team is going to the College Football Playoff. And for the second time in three seasons, Meyer will receive a hefty bonus to recognize that achievement, win or lose, once again to the tune of $250,000.

Paul Chryst, head football coach at Wisconsin, will receive a $16,000 bonus after his Badgers appeared, but lost, in the Big Ten Championship Game on Saturday. At Rutgers, women’s soccer coach Michael O’Neill earned a $6,000 bonus this year after his Scarlet Knights qualified for the NCAA tournament.

This additional compensation was earned by the coaches for the on-field performance of their student-athletes. But, as the label applies, the athletes are students first.

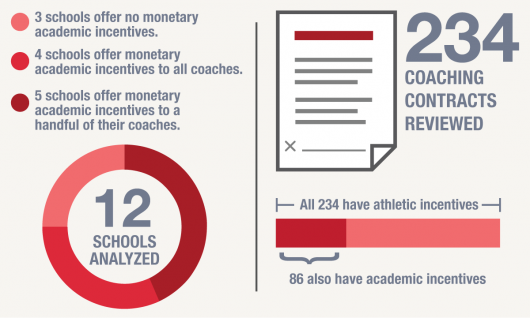

Contract-guaranteed bonuses for athletic performance are the norm across the Big Ten, and college athletics in general. However, a months-long Lantern analysis of 234 head-coaching contracts from 12 Big Ten universities showed academic bonuses are largely absent. Depending on the way academic bonuses are structured, athletic bonuses often can be worth more.

Some coaches do get bonuses for in-class performance. Though it’s less than the national-championship bonus, Meyer can make $150,000 if his team earns at least a cumulative 3.5 grade-point average.

Nearly two out of every three obtained contracts do not contain academic incentives for student-athletes’ in-class achievements.

Meyer and O’Neill are two of 86 coaches whose contracts include both incentives.

Chryst’s agreement is one of 148 that include only athletic bonuses.

These findings — that coaches’ contracts are far more likely to have bonuses for on-field performance than for in-class performance — mirror the findings of similar academic studies of coaching incentives and, in the age of commercialization in collegiate sports, further complicate the use of the term “student-athlete.”

Credit: Jose Luis Lacar | Design Editor

“Almost everybody gives athletic incentives, but not everybody gives academic incentives, and that brings up a big question: ‘Why?’” Matt Wilson, an associate professor of sport business at Stetson University, in Florida, and a leading researcher of collegiate coaching incentives, told The Lantern. “When you’re calling them student-athletes, but incentivizing the coaches for athlete-student, that’s kind of a shift in the paradigm.”

The reasoning behind the way each school creates compensation packages is far from simple, said Julie Vannatta, senior associate general counsel for athletics at OSU.

“A lot of things go into the compensation packages for coaches, and there are a lot of factors that go into that,” she said. “Bonuses and incentives are one element of a coach’s compensation package.”

Wilson agreed and cited some of the factors that could play a part in crafting compensation packages, such as what individual coaches negotiate for, the past success of a team — both academically and athletically — and, in some cases, interpretation of laws.

“No two contracts will be the same,” said Wilson, who has published two papers on coaching incentives since 2011, with a third currently in the peer-review process. “It’s a school-by-school thing, and it drills all the way down to a sport-by-sport thing.”

The contracts examined for this article were obtained from the 12 universities using public-records requests. Since Northwestern and Penn State are exempt from freedom of information laws, their compensation packages are not included in the comparative analysis.

At OSU, three of the 26 contracts reviewed have both academic and athletic incentives: Meyer’s, men’s basketball coach Thad Matta’s and women’s basketball coach Kevin McGuff’s.

Vannatta said the sports at OSU that have academic incentives “developed years ago.” Though she said she cannot recall specifically how those three were decided upon, Vannatta offered likely reasons.

“I do know that those sports are under a lot of scrutiny, and there’s a lot of pressure on those sports,” she said. “There are some teams where we’re trying to raise the academic achievement of student-athletes on that team, and some teams have very high GPAs and don’t need any incentive. Those were teams that were decided years ago that academic incentives made sense for them.”

Three schools — Michigan State, Nebraska and Wisconsin — have no monetary academic incentives in reviewed contracts. Minnesota, Rutgers, Purdue and Iowa, on the other hand, offer monetary academic incentives to every head coach.

The remaining five schools — Ohio State, Michigan, Illinois, Indiana and Maryland — offer them to only a select few coaches. All 234 contracts include athletic bonuses.

The total number of contracts reviewed does not perfectly mirror the number of varsity sports at the 12 included universities examined, because often in the cases of track and field and cross country, as well as swimming and diving, one contract was provided for the overseer of the broader program.

At the University of Michigan, for example, only the contract of Michael Bottom, the head coach for men’s and women’s swimming and diving, was reviewed.

The types of academic incentives

The most common types of academic incentives generally are based on three measures: grade point average, graduation rates and the Academic Progress Report.

The APR calculation was created by the NCAA in 2003 to measure athlete retention and eligibility. A score of 1,000 would signal every athlete remained eligible and came back to school.

To be eligible to participate in NCAA championships, “teams must earn a 930 four-year average APR or a 940 average over the most recent two years,” according to the NCAA’s website.

OSU’s academic incentives are based on annual cumulative team GPA. The three coaches have the same benchmarks and compensation.

An average between 3.0 to 3.29 would result in the coach receiving $50,000. The bonus becomes $100,000 if the figure falls between 3.3 and 3.49, while the payment is $150,000 for an average of 3.5 or above.

The uniformity was purposeful, Vannatta said.

“We looked at that intentionally and critically,” she said. “It was important to us that it was the same.”

The schools with the most similar academic-to-athletic-incentive ratio to OSU are Indiana, Illinois and and Maryland. Though they have substantially fewer varsity sports compared with OSU, they offer academic incentives to comparable teams, both in the number of coaches who have those incentives and the sports which have them.

At Indiana, the only difference is, in addition to football and both basketball teams, baseball coach Chris Lemonis has both academic and athletic incentives. His academic incentive is for annual cumulative team GPA. The most Lemonis can earn is $25,000 if the team’s GPA is 3.3 or above. The smallest bonus he could earn is $13,000 for a 2.7 GPA.

Indiana women’s basketball coach Teri Moren’s academic incentive is also based on GPA, but there are differences for Tom Crean and the recently fired Kevin Wilson, Indianan’s men’s basketball coach and the football coach, respectively. In addition to cumulative GPA, Kevin Wilson and Crean were eligible for bonuses if their teams obtain certain APR scores and graduation success rates.

If each team were to meet the highest listed benchmark for the three incentive categories — GPA, graduation success rate and APR — the maximum Kevin Wilson and Crean could each earn is $55,000. If the Hoosiers won the Big Ten Tournament, for comparison, Crean would earn $50,000. Winning Big Ten Coach of the Year would equal a $50,000 payout for Kevin Wilson.

Minnesota football coach Tracy Claeys and men’s basketball coach Richard Pitino are the only other coaches who have incentives for all three academic incentives: GPA, APR and graduation success rates.

“When you’re calling them student-athletes, but incentivizing the coaches for athlete-student, that’s kind of a shift in the paradigm.” — Matt Wilson, associate professor of sport business at Stetson University

The programs at Illinois with academic and athletic incentives match OSU. Like Meyer, football coach Lovie Smith, who is in his first season at Illinois, is compensated for cumulative team GPA. Smith’s maximum academic bonus is $50,000 per semester for a 3.0 or above, while a team average of 2.75 to 2.99 would result in a $25,000 payout and $12,500 for an average between 2.5 to 2.74.

Underscoring the points about the distinct nature of individual contracts made by Matt Wilson, the sports researcher at Stetson University, and Vannatta, OSU’s athletics lawyer, Smith’s predecessor, Tim Beckman, did not have any academic incentives in his contract at Illinois, according to The Lantern’s review.

The reverse happened when Maryland recently made a coaching change. Current head coach and former Michigan assistant D.J. Durkin does not have a monetary academic incentive in his contract, but Randy Edsall, who Durkin replaced in December 2015, did have a compensation package that included such bonuses.

“It’s a living document,” Matt Wilson said. “So it’s all about the particular circumstances of that hire at a particular time.”

Maryland stands out, however, with one of the most distinct incentive structures in the conference.

Though four of the 16 Maryland contracts reviewed have monetary academic bonuses — wrestling coach Kerry McCoy, women’s tennis coach Daria Panova, men’s lacrosse coach John Tillman and men’s basketball coach Mark Turgeon — every coach will forfeit athletic bonuses if his or her team does not meet the NCAA’s APR “cut score,” which is currently 930.

Matt Wilson said he has seen this kind of structure in a few contracts at non-Big Ten schools, like Connecticut and San Diego.

“And what does that do? It allows the school to be able sit there and say, ‘We hold academics at a certain standard,’” he said. “‘It’s not just about athletics at our place, because our coaches can’t get their athletic bonuses unless their kids are doing the job in the classroom, which is the reason why they’re here.’”

How academics vary

Each of the four schools offering academic incentives to every coach — Minnesota, Rutgers, Purdue and Iowa — does it slightly differently. The common theme is a uniform policy that every coach is subjected to, with a couple exceptions for particular sports.

At Purdue, each of the 13 of the 15 contracts reviewed incentivizes coaches for reaching graduation success rates and team cumulative GPA benchmarks. When The Lantern contacted the university for an interview request about its incentive policy, a Purdue spokesman declined to make its athletic director, Mike Bobinski, available because he was hired in August.

Purdue’s two outlier contracts — for women’s golf coach Devon Brouse and men’s swimming and diving coach Daniel Ross, who is in his 31st year — were signed in 1998 and 1999, respectively.

When a coach is hired at Iowa, he or she is subject to the university’s “Performance Incentive Policy,” said Lyla Clerry, associate athletics director for compliance at Iowa. During their first five seasons, she said, coaches can earn up to 5 percent of their base salary if their team meets or exceeds a predetermined APR score. That score is calculated by taking the national and conference average for each sport.

After five years, when a coach’s contract is renegotiated, the opportunity to earn a bonus for APR or six-year graduation rate is added, Clerry said. There are, however, two exceptions to this policy.

For his only academic incentive, Iowa football coach Kirk Ferentz, who has held his position since 1999, would receive $100,000 if the student-athletes achieve a graduation success rate of at least 80 percent, without the six-year time constraint. By contrast, if the Hawkeyes win eight games, which they did this season, Ferentz receives a $500,000 bonus.

The other exception is Iowa baseball coach Rick Heller, who, in addition to APR incentives, can earn $5,000 if his team has a federal graduation rate ranking in the top four for Big Ten baseball teams. Heller would receive a $50,000 bonus and 20 percent increase to his base salary of $155,000 if the Hawkeyes won the national championship.

Of the 18 contracts reviewed from Minnesota, 12 are under the athletic department’s standard incentive program for both academics and athletics. That academic bonus, according to a copy of the program provided to The Lantern, is $500 if the team has a “cumulative GPA of 3.2 or higher at the conclusion of the academic year.”

In addition to the $500 for GPA achievements, Minnesota baseball coach John Anderson can earn up to $5,000 in APR bonuses if his team’s score is 990 or above. Women’s basketball coach Marlene Stollings has GPA bonuses and APR bonuses, as well, but her compensation ceiling is higher. She could earn a maximum of $30,000 in academic bonuses.

Even higher is the ceiling for Don Lucia, the men’s hockey coach. Lucia can earn up to $32,500 annually in APR and cumulative GPA bonuses. The case of Lucia reinforces a point Matt Wilson made about school-to-school and sport-to-sport variation.

“Some schools will have a basic template, and then they’ll fit numbers into it,” he said. “But in some cases, they may have a wrestling program that is considered on par with their football program, and that coach might have a different structure from the standpoint of added incentives compared to another wrestling coach in the same conference where the school doesn’t view that program at the same level.”

“Incentivizing non-athletic aspects could encourage coaches to direct a student to a path that is not in the overall best interest of the student-athlete.” — Statement from University of Nebraska

A little more than one in three coaches with academic incentives are linked to graduation rates, making it the least common of the in-class bonuses. Matt Wilson said some schools removed it from their “cache of academic incentives” after a 2010 decision from the Department of Education, which strengthened prohibitions against incentivizing certain academic feats.

The prohibitions, first instituted in 1992, had never been applied to athletics personnel, but there still was longstanding ambiguity. The 2010 ruling only exacerbated it, Matt Wilson said. He and his research colleagues soon noticed a decline in academic incentives nationally, he explained. In November 2015, however, the prohibitions were lifted after two federal appeals court rulings found the Department of Education did not provide satisfactory reasoning for having them in place.

For some, no academic bonuses

Wisconsin, Michigan State and Nebraska are the three Big Ten schools with no academic incentives included in the contracts reviewed by The Lantern.

Michigan State and Nebraska used to include some form of academic incentive, Matt Wilson recalled. When talking about the Department of Education’s 2010 ruling, he specifically mentioned those two programs as ones that removed incentives around the time of its announcement. He didn’t say for sure if the strengthened prohibitions were the impetus, and when asked for comment, Michigan State did not respond.

Nebraska provided the following statement: “We expect coaches to create a culture of academic and social success in his or her role as coach at Nebraska, and have hired talented support staffs to guide student-athletes in their journey. Incentivizing non-athletic aspects could encourage coaches to direct a student to a path that is not in the overall best interest of the student-athlete. For these reasons we have chosen to focus bonus opportunities on athletic achievement, and empower student-athletes to dictate their own academic and social goals.”

Wisconsin did not respond to a request for comment regarding its policy.

The only contract at Michigan with an academic incentive was Jim Harbaugh’s, the football coach. Hired in December 2014, Harbaugh will receive “an amount not to exceed $150,000” if his team’s APR score is above 960.

Matt Wilson pointed to Michigan as a possible example of the differing expectations across universities. To explain, he also brought up the contract of Geno Auriemma, the women’s basketball coach at Connecticut, which is in the American Athletic Conference. Under Auriemma’s leadership, the Huskies have advanced to the Final Four nine straight seasons, winning the title six times.

Auriemma doesn’t get a bonus for making the NCAA tournament, Matt Wilson said. It’s the expectation there. By contrast, each of the 12 women’s basketball contracts reviewed by The Lantern included a monetary bonus for making the tournament.

And so Michigan, widely considered one of the top academic schools in the Big Ten, might not feel the need to incentivize academics, Matt Wilson conjectured.

“They might sit there and say, ‘We’re an academic institution to begin with and so we don’t give bonuses for academics,’” he said. “ ‘It’s what the kids are supposed to do.’”

Contracts built for winning

There is, of course, no right conclusion to draw from the way universities should craft coaching incentives. The distinct nature of each contract negotiation, each university’s expectations and each particular team’s track record make a blanket policy unrealistic.

Despite his continued research on the topic, Matt Wilson does recognize the reality of the situation at hand.

“Obviously in today’s day and age, coaches have to win,” he said. “The alumni base, university, they want a winning program. The glamour comes from getting bowl eligible for a football team. The glamour comes from winning games. The glamour isn’t coming from, and it’s not publicized, from a student getting a 3.8 in the classroom.”