Letter to the editor:

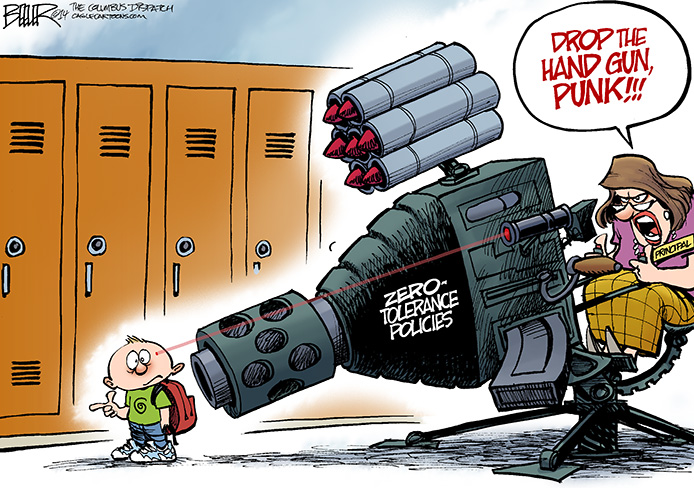

On March 4, an article ran in the Columbus Dispatch about a fifth grader from Devonshire Elementary School who received a three-day suspension for making his fingers into the shape of a gun. This is a prime example of the negative impacts of zero tolerance disciplinary policies.

In 1998, the state of Ohio required school districts to “adopt a policy of zero tolerance for violent, disruptive, or inappropriate behavior, including excessive truancy.” It’s easy to see the appeal of zero tolerance. The idea is that if the problems can be removed from the classroom, it will be easier for everyday school functions to take place. By treating all offenses the same, zero tolerance takes the burden of deciding punishment off of principals. However, the problems that zero tolerance tries to fix are not problems — they’re students.

The story of the student from Devonshire hit home for me. I am a graduate of Columbus City Schools, and I don’t believe students at Devonshire Elementary — or any kids of such a young age — are violent thugs. Unfortunately, as a 2012 report from Children’s Defense Fund-Ohio shows, injustices resulting from zero tolerance policies aren’t unusual. Zero tolerance affects students in urban schools all across Ohio especially unfairly because these students are perceived as more disruptive and threatening. They are often removed from school for nonviolent offenses, and, as a result, they fall into a vicious cycle of suspensions and become more likely to lag behind academically because of missed instruction time. This vicious cycle can be seen in a Maryland study that found, out of 74,594 students suspended in the 2006-07 school year across the state, 28,431 were suspended multiple times, and 3,728 were suspended five or more times.

Once a student returns to school from a suspension, particularly a long-term suspension, it becomes more difficult for them to catch up on schoolwork. Missing school has a negative impact on learning and results in lower grades and test scores, and can contribute to other behavioral issues which then lead to more suspensions. In fact, according to a 2013 UCLA study, being suspended just once in ninth grade makes a student twice as likely to drop out as a student who has not been suspended. Ironically, even truancy — missing school — is an offense that is punishable by suspension — missing school — under zero tolerance. Students who get caught in this cycle of suspension are prone to drop out of school and engage in behaviors that could put them in the hands of the juvenile or criminal justice system. This school-to-prison pipeline is a very real phenomenon in Ohio, and zero tolerance makes it worse, not better.

In the Senate and House Education Committees of the Ohio Legislature, there are currently two identical bills, SB 167 and HB 443, which, if passed, would repeal zero tolerance disciplinary policies. School districts across the state would gain more control over their own discipline systems. Instead of treating all disruptive behavior, violent or otherwise, the same way, specific instances could be handled on a case-by-case basis — meaning a 10-year-old playing around in class wouldn’t have to be treated like a violent offender. Students don’t act out for no reason, and so trying to understand why students become disruptive and helping them, rather than throwing them out of the building, could do wonders for school environments. Suspensions would decrease and more students would be in class.

I call on Ohioans who don’t want to see kids treated as criminals to call their legislators and let them know. People around the state are expressing support for SB 167 and HB 443 so schools can once again be a place of learning for all students. Through this legislation, we can help make sure that students stay in school and are prepared to make this city, state, and country the best it can be.

Benjamin Alexander

Member of Students for Education Reform

First-year in education

[email protected]