Ohio State’s tuition isn’t cheap, but when compared to other Big Ten universities, it seems it could be worse.

Since 2007, the in-state tuition rate at OSU has risen nearly 16 percent and students graduate with an average of more than $25,000 in debt, according to a Board of Trustees document.

The flagship program of Undergraduate Student Government last year aimed to boost affordability. And last week, vice president of Student Life Javaune Adams-Gaston spoke to the Board about the need to increase students’ financial literacy.

But the Board said tuition isn’t that bad.

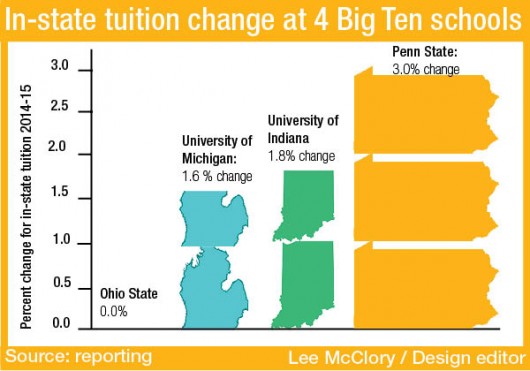

For the second straight year, the Board froze in-state tuition, keeping it at $10,037 for the 2014-15 academic year. While University of Minnesota and University of Nebraska did the same, the other schools in the Big Ten raised their in-state rates an average of about 1.9 percent.

OSU’s increase of 16 percent since 2007 is only about 2 percentage points above inflation, according to the consumer price index. OSU also has the fifth-lowest in-state tuition in the conference at $10,037 — the average in-state tuition is $14,424.

While it might seem like tuition would correlate with how prestigious the school’s academics are, OSU outperforms others with similar tuition. The university is currently ranked 52nd by U.S. News and World Report, five places higher than the Big Ten average of 57. No other school in the conference with cheaper tuition has a higher ranking.

OSU also compares well to similar universities outside of the Big Ten. University of California-Los Angeles and the University of Washington both froze tuition this year, but both have higher tuitions at $12,697 and $12,397, respectively. The University of Arizona and the University of Florida have both seen tuition increases of more than 5 percent this year, though Florida’s in-state tuition currently stands at a mere $6,630, according to a Board document.

Despite the 5 percent increase for the out-of-state surchage, OSU remains competitive in that area as well, with the third lowest out-of-state tuition in the Big Ten in 2013-14, behind only Nebraska and Minnesota, according to the National Center for Education Statistics data from 2013-14.

Keeping tuition low is a continuing struggle for universities, and has been exacerbated in recent decades by the decline of state funding and increase in student demand for modern facilities.

“It is … important to note that tuition levels are a product of relative state support and history,” OSU spokesman Gary Lewis said in a June email. “Institutions such as Nebraska that receive more revenue from state appropriations than from tuition and fees historically have lower rates of tuition.”

Lewis said OSU’s ability to freeze tuition has come in part because of its recent monetization of assets and reducing expenses.

Though tuition in Ohio is middle-of-the-road compared to the rest of the country, it has some of the weakest state support, according to a 2012 article from The Columbus Dispatch. State funding has declined 3 percent in the last year, according to a Board document. The state provided 25 percent of the university’s funding in 1990, according to an article from the Dispatch, and it was a mere 7 percent in 2012. The trend is significant enough that members of the Presidential Search Committee to replace E. Gordon Gee said working with state legislators would be a key quality for the new president to have, according to a presidential profile that was created for that search.

It’s also a trend that USG President Celia Wright, a fourth-year in public health, is particularly concerned about.

“I am impressed that Ohio State has been able to keep tuition low because when you look at debt, Ohio is really failing families compared to other states. Ohio really stands out as one of the worst states for state support,” she said, adding that students should consider that when they go into voting booths.

In September 2013, former Interim President Joseph Alutto spoke to The Lantern about the difficulty of staying academically competitive without spending money.

“You can bring great students to an institution, you can hire great faculty, but unless you create programs, it doesn’t pay off for either one of them … we (must) continue to have new programs, strengthen the programs we have, and decide how to distribute those resources of students to faculty,” he said.

He also said, though, there were areas where the university could do better in containing its costs.

“Any institution as large as Ohio State has areas where it can do a better job of restraining and controlling cost issues,” he said. “I know that there (are) areas where we could do things better and more efficiently, which means we take some of the pressure off the affordability question.”

For Wright, the biggest difference needs to come in the form of lower student fees.

“Ohio State does a good job with tuition, but the biggest cost increases have come from the fees they charge students. Even though we may be one of the best, improvements can and should be made in regard to fees,” she said.

This academic year, full-time OSU students pay about $434 per semester in fees, ranging from a general fee to a recreational fee to a student activity fee.

The Board announced a freeze on the tuition for the 2014-15 school year at its June meeting. At that meeting, chief financial officer Geoff Chatas said it was a difficult task to manage a second consecutive tuition freeze and still have enough money.

Trustee Michael Gasser, who chairs the Financial Committee, praised the proposal but also suggested the recent trend of tuition freezes needs to be re-examined in coming years so the university doesn’t see a drop-off in the quality of its services.

Despite the new methods of revenue generation, Lewis also said it might not be possible to keep freezing tuition in the future.