“The adequacy of every state’s response to sexual assault is being called into question,” said one lawyer on what he believes will be a rippling effect of California’s recent adoption of the “yes means yes” law. It focuses on the importance of affirmative consent, rather than the absence of a no, during sexual activities.

Although the state of Ohio has not adopted the “yes means yes” law that California did in late September, Ohio State has similar affirmative consent language woven through its Code of Student Conduct and Student Wellness Center’s resources.

These policies, however, do not hold the legal weight that a state law does. The Code of Student Conduct includes university expectations only.

“A student who violates the code is subject to disciplinary procedures by the university. As far as a legal thing, it’s totally separate,” said Dave Isaacs, spokesman for the Office of Student Life.

With increased national attention to the subject after California’s law adoption, it might not be long before other states follow suit, said Frank LoMonte, lawyer and executive director of the Student Press Law Center.

“I don’t think that there’s any question that other states will start looking at this because they are feeling the need to do more,” he said. “I think you will see a lot of legislators trying to demonstrate that they take these cases seriously.”

Since the passing of California’s law, Gov. Andrew Cuomo instructed the State University of New York, consisting of 64 campuses, to alter its policies to make affirmative consent the policy, according to The New York Times.

In New Hampshire, Representative Renny Cushing has filed a bill for the state’s college campuses to also adopt a “yes means yes” policy.

More than 20 years ago, Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio implemented the first “yes means yes” concept. At the time, the policy received criticism and was mocked on “Saturday Night Live.”

The White House’s launch of the “It’s On Us” campaign against sexual assault on college campuses on Sept. 19 has also contributed to the national attention the subject has garnered recently. The campaign aims to take the burden off survivors of sexual assault by encouraging everyone to do their part to fight the issue of sexual assault on campus, according to the White House website.

OSU’s pro-consent policies, initiatives

Along with the information regarding sexual misconduct and consent in the Code of Student Conduct, the Student Wellness Center also has a webpage dedicated to the topic of consent.

The page exists because of the complexity of the topic of consent, said Michelle Bangen, sexual violence prevention coordinator at OSU.

“We know that sexual consent is one of the most confusing topics for college students and probably the most misunderstood topic with regard to sexual violence and sexual assault,” Bangen said.

Both the Code of Student Conduct and the Student Wellness Center’s consent page have language and ideas similar to those in the “yes means yes” law.

One similarity is the notion that consent should be given throughout the course of sexual activity.

“Affirmative consent must be ongoing throughout a sexual activity and can be revoked at any time,” reads the California bill.

“If consent is not obtained prior to each act of sexual behavior (from kissing to intercourse), it is not consensual sex,” reads the Student Wellness Center’s consent page.

“I think it’s really important that we educate people that they need consent every step of the way because there’s a lot of times when individuals may think that it’s implied by body language or by previous sexual activities,” Bangen said. “Two individuals may be perfectly happy and fine doing one activity, and if an individual assumes that they have consent for the next thing, that can definitely lead to a nonconsensual situation and sexual assault.”

The basic notion of the California law is also comparable with OSU policies. “Lack of protest or resistance does not mean consent, nor does silence mean consent,” reads the “yes means yes” law. The Student Wellness Center’s consent page states, “The absence of ‘no’ does not mean ‘yes.’”

Likewise, the Code of Student Conduct defines consent as “affirmatively agreeing” to partake in sexual activity. This language, as well as the stipulations that “consent may be withdrawn at any time” and “prior sexual activity or relationship does not, in and of itself, constitute consent” were all additions to the Code of Student Conduct in June 2012, when its consent policies were revised from its December 2007 version, Isaacs said.

This idea of focusing on affirmative consent, rather than the lack of refusal, which is woven through both the California law and OSU’s consent initiatives, is important for individuals who might not feel comfortable saying no, Bangen said.

“The (responsibility) is on the initiator to gain consent. It’s not on the other person to say no,” she said.

The Student Wellness Center’s webpage also features photos from their “Consent is Sexy” campaign, which aims to inform students on how talking and getting consent should be a good thing and not awkward like some might think, Bangen said.

“The ‘consent is sexy’ campaign was really developed as a way to get students talking about the issue and also feeling more comfortable with it,” she said.

One of the images reads, “No is not yes. Drunk is not yes. Not sure is not yes. Silence is not yes.” In larger text at the bottom, it says, “Yes is Yes.”

Whereas the Student Wellness Center focuses on prevention and education, the Student Advocacy Center and Counseling and Consultation Service are where students can get help if they are sexually assaulted, Bangen said.

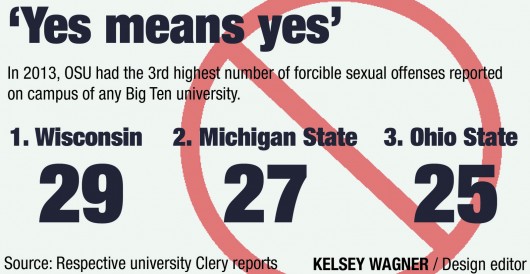

Comparing reported sexual offenses among Big 10 universities

OSU had the third highest number of forcible sexual offenses reported on campus in 2013 of any Big 10 university, according to respective universities’ annual safety reports. Universities are required by law to annually provide certain crime data occurring on campus to students.

The University of Wisconsin had the most with 29 reported. The University of Iowa and University of Nebraska-Lincoln both had the fewest with four reported each.

Still, these statistics only reflect the number of reported offenses and thus are not necessarily reflective of which university has more or less sexual assaults occurring on its campus.

The National Research Council estimates 80 percent of sexual assaults go unreported, according to a November 2013 article from USA Today.

“There are so many variables that go into that calculation that it’s dangerous to say that one campus is safer than another based off nothing but (annual crime statistics),” LoMonte said.

LoMonte used the example of how colleges with lower sexual assault statistics could be more dangerous than those with a higher number reported.

“I’m not really sure I would regard a college with a zero in its crime report as being a safe place. I think you could equally infer that that’s a place that isn’t honest with its students about crime or a place that discourages people from reporting,” he said.

So far this year, OSU has issued eight public safety notices. Four were related to sexual assaults, two were related to robberies, one was related to an armed robbery and one was related to an attempted armed robbery.

Kara Spada, a fourth-year in political science, said she thought the number of forcible sexual offenses that occurred on OSU’s campus last year, 25, was “alarming” in comparison to the largeness of the university.

“Twenty-five seems low generally compared to what I expected it to be, it being such a busy university,” Spada said.

Steven Pesa, a third-year in economics, also referenced the size of the university when voicing his thoughts on the number of sexual assaults that occurred at OSU but said he thought the number could be lower. “Obviously, the ideal number is zero, but it’s not too bad considering we have, like, 50,000 people on campus,” he said.

Spada said she thought OSU having the third highest number reported in the Big 10 was surprising, considering she thought the number was low.

“It’s surprising to me because the numbers are so low, but you hear so many more stories about things happening. It sounds like so many are going unreported,” she said.

Pesa, however, said he did not find OSU having the third highest alarming. “We have more people — more people, more problems,” he said.

As for his thoughts on whether he would like to see Ohio adopt the “yes means yes” law, he said he thought the law might help “the legality of the situation” but not necessarily change the culture.

Spada said she would like to see Ohio adopt “yes means yes” or some kind of new policy regarding sexual assault.

“I think any sort of law to help an issue like this would be beneficial,” she said.