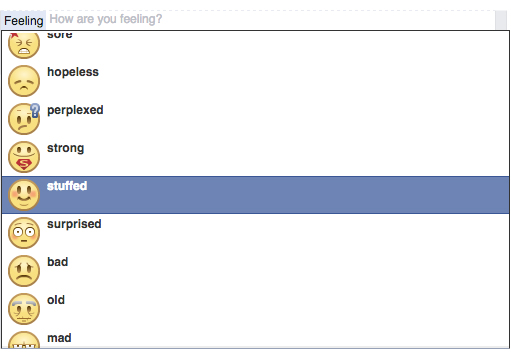

Facebook’s ‘fat’ emotion was changed to ‘stuffed’ after an online campaign against the word.

Credit: Screenshot of Facebook

Editor’s note: This opinion piece contains explicit language.

Colored. Orientals. Faggot. Retard. None of these words are acceptable in the 21st century vernacular.

These are just a few examples of words with perhaps humble beginnings that are now exiled onto a list shaped by what society considers politically correct. A forward-moving culture constantly sheds the old and embraces the new, and words are no exception. Acceptable lingo, say in the ‘60s, seems like an entirely archaic language compared to that of today.

But where do we draw the line? This week, Facebook removed “feeling fat” from its status options because of a campaign that stated “fat is not a feeling.” I agree that “fat,” in any grammatical form, is not an emotion. However, fat in everyday jargon no longer focuses specifically on size or weight, so Facebook’s mistake is understandable.

Fat in informal speech might be associated with feeling unhealthy, bloated, stuffiness, etc. Is it politically incorrect for me to feel fat after stuffing my face with low-grade fast food? Not everything said is aimed to attack another individual.

I am damned if I conform and I am damned if I don’t conform.

I feel suffocated.

I no longer know how to speak in my own country and my own language.

What qualities push seemingly OK words from tolerable to intolerable? Is there a word-police out there somewhere constantly shaping word usage?

Every word is a landmine waiting to explode with a new connotation that will deem it offensive to a group or subculture. The Bill of Rights assures freedom of speech and expression, but that freedom is slowly restricted by this ethical sense of political correctness.

How am I supposed to have voice in society if something as simple as vocabulary is constantly restricted?

Don’t get me wrong, I do not condone discrimination, prejudice, nor any related matters. I advocate against labels, stereotypes and bigotry. For God’s sake — or maybe I should say for goodness sake — I live every day as a minority female in a predominantly Caucasian environment. I am just as sensitive to discrimination as any of my peers.

Extreme sensitivity to something grants it more power. These unwritten laws bring difficulty to having an open constructive discussion in settings ranging from classrooms to a local coffee shop. The damaging effects of a poor choice in words can destroy a reputation or brand no matter how innocent the intent.

Big Brother might not be watching over you, but an easily offended person could hang over your shoulder for the rest of your life.

Maybe tomorrow I will no longer be associated with “maternal” and just “female.” Maybe “Caucasian” will be deemed offensive because someone feels it is too phonetically similar to “cock-asian.”

Nonetheless, the tools given to us to instill expression seems to expire. This ongoing sensitivity feels more restrictive than protective. Flavorful ingredients are useless if the menu is only for acquired tastes, and our words are barren if connotations are blackened only with the adverse.