Growing up in Poland in a Jewish family, Esther Nisenthal Krinitz and her sister Mania were the only members of their family to survive the Holocaust. Through needlework, Krinitz shared her experiences and documented the loss and sadness that swept through Poland during World War II.

Krinitz started creating tapestries when she was 50 years old. Thirty-six of her tapestries will be on display at the Columbus Museum of Art this spring.

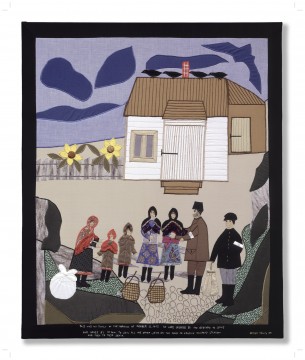

In a 1998 interview with filmmaker Lawrence Kasdam, Krinitz described the events that tore her family apart. Her family and friends were being evacuated from their homes by Nazi soldiers, but she chose to go stay with a farmer for refuge rather than go with her family, all of whom were eventually killed at a concentration camp.

“I said, ‘I’m not going.’ My father became mute — he couldn’t talk,” Krinitz said, expressing how frightened her father was..

Though Krinitz died in 2001, her memory lives on in her artwork and a short documentary film titled “Through the Eye of the Needle,” which includes the 1998 interview. Both will be shown at the CMA.

“Esther’s story of courage and remembrance is extremely moving. The fact that creative means were used to tell her story, especially by someone who did not consider herself an artist, is also profoundly moving. There are lessons in it for all of us,” Suzanne Silver, an associate professor of art said in an email.

Silver said she was able to see Krinitz’s artwork in Baltimore several years ago.

“Esther Nisenthal Krinitz’s stitched narratives provide texture — the physical texture of thread and fabric and the psychological texture and layered depth of her family’s plight,” Silver said. “It is a document of a time of horror and inhumanity. It was probably also a cathartic act for Krintiz. A way to remember and to attempt to recover from such a trauma.”

CMA curator of education Carole Genshaft said Krinitz’s work is honest and unexaggerated.

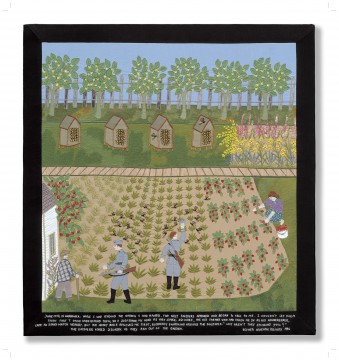

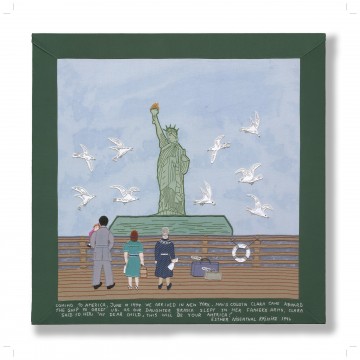

“They’re just the way she remembered it, so they’re really a very truthful and honest glance, and very personal depiction into what exactly happened to people during the Holocaust,” Genshaft said. “Each one she carefully stitched to tell what each part of the story is about, so there’s actually words on each of the pieces.”

Krinitz’s daughter, Bernice Steinhardt, will give a public lecture April 12 about her mother’s artwork.

Genshaft said there are various sections of the exhibition that explore the subjects of Poland before Nazi occupation, during the occupation, Krinitz hiding, her liberation and Jewish holidays through Krinitz’s tapestries. One of her tapestries depicts her family the morning they were forced out of their home. Another is a portrait of her husband before they left for America.

Genshaft said the tapestries show great detail, depth and texture.

“I think it’s a very important exhibition, because it’s the experience of this woman who was able to survive the Holocaust,” Genshaft said.

The exhibition opens Friday and will continue through June 14.