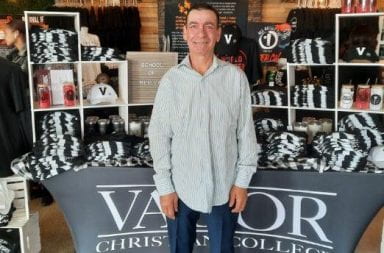

Shelby Jean, a fifth-year in social work, has recovered from an eating disorder. Credit: Amy Ann Photography

Shelby Jean first became anorexic in her freshman year of high school after she was injured and could not continue playing soccer.

“I thought I was going to get fat, so I started dieting,” she said in an email. “Everything went downhill from there. I knew it wasn’t the right thing to do, but nothing else in life seemed right either.”

Jean, a fifth-year year in social work at Ohio State, is one of up to 30 million people in the U.S. to suffer from an eating disorder, according to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders’ website.

This week is National Eating Disorder Awareness Week, and while many people have heard of anorexia nervosa, they might not have heard about the condition anorexia nostalgia, which sometimes occurs when a person is recovering from anorexia and he or she starts to miss the feelings he or she had while anorexic.

“When people are in recovery from anorexia nervosa, what happens is the noisy brain can get reactivated. Food is medicine, but food can also increase the anxious brain,” said Nichole Wood-Barcalow, a licensed psychologist and the Director of Outpatient Services at The Center For Balanced Living in Columbus.

Wood-Barcalow said that one reason why some people become anorexic is because the lack of food allows their brain to quiet, which allows them to relax, so when they feel that their brain is being too noisy, they just stop eating and the problem goes away.

She also said that those recovering from an eating disorder might feel nostalgic about the way that people treated them while they were anorexic, such as compliments for the way that they looked and the attention received when they were going through recovery. Once a person has recovered, anorexia nostalgia can manifest in missing that attention.

Some people miss the simplicity of their life while they were anorexic, Wood-Barcalow said — all they had to think about was not eating. Wood-Barcalow said she most often sees anorexia nostalgia in adolescents because they look back on those simple times and want to go back to that.

While Jean said she had never heard of anorexia nostalgia, she described eating disorders as a secret friendship that’s difficult to end.

“They become your most faithful, accessible, secret pal, which makes it so hard to give up,” Jean said.

She said that there were days during her recovery where she could not manage her feelings of guilt and emptiness and she felt unworthy of everything, despite her ability to eat again.

“It took me by surprise because nobody ever warned me about this in treatment,” Jean said. “They just wanted me to stop starving myself. I longed for my eating disorder. Like I said earlier, giving up ED means losing your best friend. I spent a lot of time in counseling focused on self-affirmations and self-esteem building, because I felt lost without ED. I hadn’t seen Shelby in years, at least without ED holding my hand. I had to relearn who Shelby really was.”

Kim Spiezio, a 48-year-old vascular ultrasound sonographer who works at the Wexner Medical Center, said she still struggles with her anorexia, which started when she was around 13 years old.

“Because I was such a (straight-laced) person and wouldn’t go into drugs to numb myself out, I wouldn’t drink alcohol to numb myself out. Starvation became my drug of choice. It was my way of numbing myself out of everything around me,” Spiezio said. “I didn’t have to think.”

She said people would tell her that she looked tired and would ask her how she felt, and she would always respond with, “I feel great.”

In 2011, Spiezio said she hit a low point and considered suicide.

“My family was sick of me, my friends were sick of me, I had no energy and would have preferred to be dead … luckily there was an inkling inside of me that just wasn’t convinced,” she said.

A friend then helped Spiezio connect with Harding Hospital, and she then got in touch with the Center For Balanced Living, where Wood-Barcalow works. She said that now she is happy and was successful in her recovery and for the first time since she was 13 years old, she is completely healthy.

“The same drive that keeps them a slave to their eating disorder … that can be turned around and that can actually, that energy can be used to help them to create a really amazing, alive, vigorous person … who doesn’t have to hide and who doesn’t have to lie,” Spiezio said.

Jean, too, has recovered from her disorder. She said she recovered in college, though she suffered a short relapse at the age of 20.

“Everything in life seemed too good to give up for ED and all the misery that goes along with it,” she said. “My eating disorder is so far gone from my identity now, it shocks me when I reminisce the way in which I lived, if you want to call it living.”

Holly Davis, a psychologist who works in the Office of Student Life Counseling and Consultation Services, said that resources about eating disorders can be found on the Counseling and Consultation Services website.