OSU President Michael Drake speaks during a tour of the Wexner Medical Center on Feb. 24. Credit: Jay Panandiker | Engagement Editor

Before Ohio State President Michael Drake was a university administrator, he was an ophthalmologist specializing in glaucoma. Drake donned the white coat again on Wednesday morning to meet with doctors from various fields at the Wexner Medical Center and to discuss their work. Drake met with doctors from the cardiovascular surgery, transplant and human genetics teams.

Drake first met with Dr. Laxmi Metha, whose work focuses on how coronary diseases and heart attacks are undertreated and underdiagnosed in women. Metha recently published a scientific statement about cardiovascular diseases in women, where she examined the discrepancy in mortality rate between men and women.

In the presentation for Drake, Metha outlined some of the reasons doctors believe the discrepancy exists — such as young women having plaque buildup on smooth muscle as opposed to traditional buildup on lipids. Additionally, these women do not receive stents, so they might walk out not believing they had a heart attack, but are frequently the same women that suffer recurring heart attacks.

She said that doctors now know more about the discrepancy in treatment because new technology allows them to know information that they would otherwise only be able to learn from an autopsy. Drake asked about the number of incidents of heart attacks in women, as well as prevention. Metha said that because of smoking rates, the number of incidents is down overall, with the exception of young women, which she classifies as being younger than 45 years old. Metha said the group has also focused on heart attack prevention.

“(For) prevention, the most important measure is checking blood pressure and cholesterol levels, as well as weight,” Metha said.

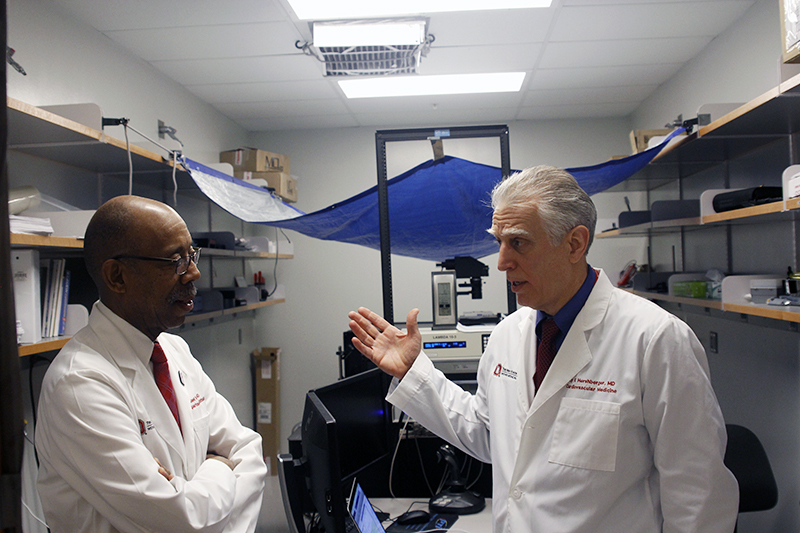

OSU President Michael Drake and Dr. Ray Hershberger chat during a tour of the Wexner Medical Center on Feb. 24. Credit: Jay Panandiker | Engagement Editor

Drake said he is meeting with Rep. Joyce Beatty, D-Columbus, later this week to discuss the Women’s Heart Alliance, to discuss prevention as well. He said OSU is one of the first universities to be involved in the project, which will aim to raise awareness about signs and symptoms.

“A lot of people grew up in the ‘Mad Men’ generation of what a heart attack was and who got one. That was men who were oversmoking and under stress,” Drake said. He added that as times have changed, acknowledging the importance of women’s heart health has become more prevalent. Drake said prevention is important — while it is great to have miracle recoveries happen at the heart hospital, it’s even better to not require the miracles in the first place.

Drake also met with members of the transplant team who work with lung, liver and heart transplants. The lung transplant program began in the late 1990s but was briefly on hiatus from 2009 until 2013. Since the program was revived, the team has performed 59 lung transplants. Drake met with Bryan Whitson and Sylvester Black, who are doctors in the transplant team. Whitson’s work has focused on lung transplants while Black’s work deals primarily with livers.

Drake asked whether Ohio was a net importer or exporter of organs. Black explained that it depends on the organ — for lungs, Ohio is a net importer, and for livers, the state is a net exporter.

“A majority of our livers are going outside (the state), but we are working hard to change that,” Black said.

Black said there are currently discussions about how to better allocate organs between states around the country — perhaps dividing the country into groups of states. Drake agreed that it is important to have more programs that share organs across states and regions to help those on the transplant list.

“The requirements for people to be in good standing on the list may be difficult, especially for low income people,” Drake said. “They may not have a car, so they would have to take a bus to a different state — they just wouldn’t do that.”

He also discussed organ perfusion rates, which range from two to three days with lungs but up to three days with livers.

“Bryan and I hope with our laboratory research can bring that up to two or three weeks,” Black said. “Once you get to two or three weeks, there’s a lot of interesting things that you can do. You can modify the organ in such a way that there may not be immunosuppression. You can take organs that are significantly damaged organs and make them transplantable.”

To end his tour of the medical center, the president met with Dr. Ray Hershberger, whose work focuses on the genetic basis for dilated cardiomyopathy. The condition results in an enlarged ventricle, which prevents the heart from pumping blood efficiently.

Hershberger said DCM is often considered idiopathic, or random, when there is no evidence of a direct familial connection to another family member. However, Hershberger has hypothesized that the condition is genetic, regardless of a direct familial connection. Hershberger and his team conducted a study of 1,300 individuals who have DCM and also recruited family members to test to determine if the DCM is familial. He said the research is important because of the mortality associated with the disease.

“We spend enormous amount of time and effort developing drugs and devices and mechanical supports and transplants,” he said. “But it is a late phase disease so it is enormous strain on health care finances in addition to the morbidity and mortality.”

Hershberger said that while he is a transplant cardiologist, he believes there has to be a better way than transplants — which is why he is doing the research. The research is shifting the concept of health and disease to include genetic information to understand risk in more ways, he said.

“We are literally rewriting the textbooks of medicine,” he said.