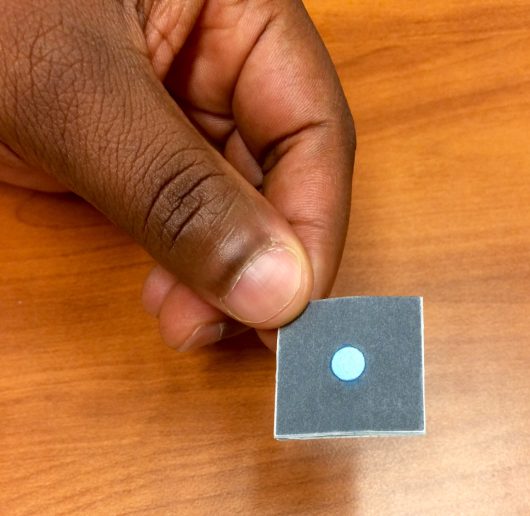

Testing for cancer could soon be as simple as using one of the paper strips shown above. Credit: Yini Liu | Lantern Reporter

Detecting cancer could soon be as easy as taking a home pregnancy test, and Ohio State scientists are already developing a second generation of paper-strip cancer tests based on a prior model they developed over the summer.

The first model of the low-cost, stamp-size paper strips contain antibodies to detect cancer antigens and malaria, diseases for which human body produces antibodies. But it can detect only one disease at a time.

The new one is slated to be able to detect four diseases simultaneously.

Abraham Badu-Tawiah, an assistant professor in the department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, developed these paper strips. He and his team calls them “on-demand diagnosis,” which means instead of going to a hospital, people now can perform tests at home. Users put a drop of blood on the strip, mail it to a laboratory and then go to a doctor if the results are positive.

Unlike the conventional testing, the paper strip removes enzymes and usesan ionic probe –– a small, synthetic chemical probe that is much more secure than enzymes. This stabilizes the testing process and enables molecules to stay on the strip forever.

“It is so stable,” said Suming Chen, a postdoctoral researcher who works with Badu, who called the ionic probe “a great advantage.” “(Having an) ionic probe to replace (the) enzyme is a great advantage here.”

The new strip is a five-layer paper device with wax on it to trace channels and control the movement of fluid. It works the same way as the old version, but is more sensitive. Results can be revealed with a handheld spectrometer —a cancer detection instrument — allowing for portability and timeliness.

“The process can be done very early on,” Badu said. “You don’t have to wait to get sick before you get diagnosed.

The paper strips can also have a trickle effect on treatment down the line.

“If you can pick (a disease) up early enough, then you still have time to treat it without much complications,” Badu said.

The convenience of the paper strip makes cancer diagnosis accessible in remote places, like Africa and Southeast Asia, where facilities are not always available and cancer kills thousands of people every year.

Besides people in remote places, Badu said people living in poor areas can also benefit from the low cost of the paper strip.

“My real goal is to empower people, to take care of their own health,” Badu said. “If you can help people realize that ‘actually, to live longer or to die, I can do something about that,’ you give them the chance to at least fight for your own life.”

The technology is licensed to a medical company for more developments. Badu’s future research will focus on more advanced paper strips that can detect more diseases.