Credit: Robert Scarpinito | Managing Editor for Design

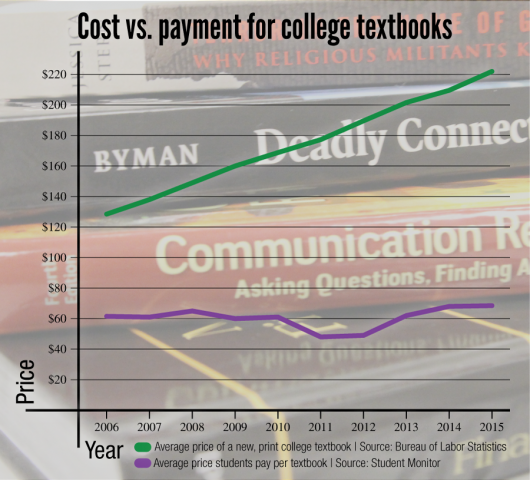

A study from the Public Interest Research Group reported textbook prices have risen more than 73 percent since 2006, meaning the face value of a new textbook has risen faster than the price of most retail goods, healthcare and even college tuition. According to the study, which was released earlier this year, the market for undergraduate textbooks is a $1.5 billion industry. The College Board recommends students budget almost $1,300 for textbooks and other course materials each year.

The prices of books

Kathy Smith, manager of Barnes & Noble at Ohio State, said the prices of textbooks at OSU are consistent with the prices of similar items at other universities. Book prices themselves are set by publishers, who sell to the bookstore at a fixed cost regardless of the quantity purchased, she said. Barnes & Noble then adds an “industry-standard margin” on top of this price to cover its costs of doing business.

Lucia Dunn, an economics professor, said publishers release new editions of textbooks too frequently, which drives up prices. Dunn specifically mentioned a representative from McGraw-Hill who once told her, if possible, publishers aim to revise books every 18 months.

“They have got the authors of these textbooks who are working on these books constantly updating it, when, in fact, there is no need to change the textbook in some fundamental areas, like economics, every 18 months,” Dunn said. “The laws of supply and demand don’t change every 18 months.”

“I think they know they have the students over a barrel, and they are taking advantage of them.” — Lucia Dunn, professor of economics

Bart Snapp, a math professor, also said he thinks textbook publishers update books too often.

“I really don’t know of a time where I thought to myself, ‘A new edition of the textbook is out, oh good,’” Snapp said. “Usually I think, ‘Oh I don’t want that, I want the old one.’”

Dunn, who last taught classes in Fall 2015, said cost was definitely a factor when she considered changing a textbook, as she sees the prices of books as something that add heavily to student debt.

“I think they know they have the students over a barrel, and they are taking advantage of them,” she said.

The industry’s response

Representatives from the textbook publishing industry disagree with these criticisms, including Marisa Bluestone, director of communications at the Association of American Publishers — a trade group that represents many publishers, including Cengage, McGraw-Hill and Pearson Education. Bluestone said the actual prices that students pay for textbooks, as opposed to the face value of the book itself, fell between 2014-15 and 2015-16. Bluestone attributed this to savvy student consumers and the shift from print to digital textbooks.

“The industry recognizes that the sticker price of print materials can be quite high, and that’s one of the reasons — that and students do better with (digital textbooks) — are the two big reasons that the industry is moving from print to digital,” said David Anderson, executive director of higher education for AAP.

Anderson added that the prices of textbooks have risen, just as they do for any other product. He said, however, that as the industry becomes more digitally based, prices will go down, and so far some prices have dropped as much as 40 to 60 percent.

“I don’t know of anyone else in the higher-education ecosystem who can say they have lowered prices like that,” he said.

Anderson said the general industry standard is to release a new edition of a textbook every three to four years. He added that this usually depends on changes in the field or if the publisher recognizes a new way to teach the material.

“If you’re looking at an accounting book dealing with taxation, and you’re dealing with a tax that was repealed or amended two years ago, that’s not a useful textbook,” he said.

Alternatives

All of this has led to innovative solutions by professors to help students keep prices low. Dunn, for example, said she allows students to use older editions of textbooks instead of newer ones, and provides students with chapter assignments to accompany it.

“The faculty are trying to help the students that way, but a lot of students are worried about using the older edition, so it doesn’t work perfectly,” she said.

Another way to lower prices is creating open-source textbooks like the one created by Snapp, titled Ximera, which is available for free online for calculus classes and provides students with real-time feedback on their performance. Since the book is open source, anyone can suggest edits to the book to Snapp, allowing the book to be updated easily. The textbook has been used in several sections of Calculus I at OSU. Snapp said students are happy the book is free, compared with the traditional $120 calculus text. Snapp also is able to gather data and see how students are using the textbook, in the same way that textbook publishers can.

“When we know how the students use the system, we can write (the book) better so they learn better,” he said. “That’s typically information that is hard to get out of the publisher.”

Rather than use a traditional textbook, Ty Shepfer, a management and human resources professor, has his classes use a compilation of articles from various academic journals. He said a traditional textbook might not include all of the material a professor wants to cover, and therefore might result in supplemental materials being necessary for the class. Moreover, since the material is specifically tailored to his class, no portion of the compilation goes unused, he said. He also said he thinks it is important that other professors also consider the price of a textbook when designing their classes.

“As a land-grant institution, I think that it is critical that every faculty member at Ohio State consider the cost of their course materials,” Shepfer said in an email. “If there is anything that I can do to promote affordability and access, I try to do it as this is in line with (University) President (Michael) Drake’s vision. While it may be a small part, if everyone does their part, it can truly make a difference.”

The rise of rentals

A newer development in the textbook industry is the rental textbook market. Smith, of Barnes & Noble at OSU, said renting textbooks has become a popular option at OSU.

“Textbook rentals are an extremely popular option because they save money up front,” Smith said in an email. “This is particularly important for students who cannot afford to lay out a larger amount of money for textbooks and then wait three months or more to return books for buyback.”

Smith said the rental option has been well-received at OSU, and students can save 35 to 50 percent renting a new book instead of buying it, and 50 to 80 percent doing the same with used textbooks.

Dunn said that if this market expands, it would help students a great deal. However, she said students who rent a textbook lose the ability to go back and reference it in future semesters.

Anderson said he believes the concerns about high textbook prices will go away as the industry shifts to more digitally based books.

“We’re moving from a print world where most of the price issues exist into a digital world where most of those issues are very much diminished or go away all together.

Dunn, however, took a different view.

“It’s price gouging, that’s my opinion. It’s price gouging.”