[author image=”https://www.thelantern.com/files/2017/07/Abigail-Vesoulis-v6l7df.jpg” ]Abby Vesoulis produced this content in her role as Patricia B Miller Editor. [/author]

A graduate sits in the bleachers of Ohio Stadium with his decorated cap, awaiting the beginning of 2016 Spring Commencement. Credit: Mason Swires | Assistant Photo Editor

Matt Gaines, a senior at Walnut Hills High School in Cincinnati, wanted to pursue an electrical engineering degree at Ohio State. After scoring a 34 on the ACT and earning a 3.58 unweighted GPA, he thought his chances of admission were pretty high.

Instead, he was put on a waitlist for admittance to OSU’s incoming 2017 freshman class. He said he now feels the system is flawed.

“I had no concerns of not getting into Ohio State. Maybe MIT, but not Ohio State,” Gaines said. “I know people who got in with a 27 ACT and a lower GPA than me.”

Data obtained through a public records request shows more and more accepted and enrolled students are achieving higher test scores and graduating at the top of their respective high school classes. OSU seniors preparing for commencement in a few weeks might wonder if they would have gotten into the university if they applied today, rather than four years ago.

According to a Lantern analysis, that answer isn’t “No.” But it’s not a firm “Yes” either.

“I don’t think I would be as confident in applying, knowing the data and knowing how increasingly difficult it is to get into this university.” — David Straka, graduating fifth-year

Adding to the uncertainty of admission are applicants’ climbing test scores, a decreasing reliance by high schools on traditional class ranking systems, an exorbitant increase in applicants to OSU, and trends along gender lines in admissions cycles.

David Straka, a graduating fifth-year in political science and a National Buckeye Scholarship recipient, got a 28 on his ACT. He said he does not know if he would have been accepted under the same scrutiny by which the incoming freshmen class is being judged.

“I don’t think I would be as confident in applying, knowing the data and knowing how increasingly difficult it is to get into this university,” he said. “I don’t know that I could have any bit of confidence in getting in.”

Climbing scores

Credit: Robert Scarpinito | Managing Editor for Design

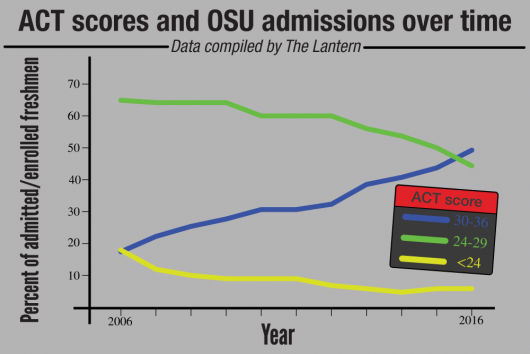

In 2006, 5,507 freshmen who went on to be enrolled at OSU submitted the ACT as application materials. Less than one in five of those students who submitted the ACT scored between a 30 and a 36.

Fast forward to last year, nearly half of the 6,635 admitted freshmen who submitted their ACT results to OSU posted scores in that range.

Nearly two-thirds of enrolled OSU freshmen who submitted the ACT scored in the 24-29 range in 2006. Less than half – 45 percent of enrolled freshmen submitting the test – scored in that range last year.

A 24 on the ACT is a better score than 74 percent of test takers, according to the American College Testing service, the nonprofit that administers the ACT. The national average is a 20.

Only 6 percent of enrolled freshmen who took the ACT scored below 24 in 2016, whereas 18 percent were in that test score range 10 years ago.

Current students find an advantage

OSU’s admissions standards are undoubtedly becoming more difficult, and while that might hurt prospective students who are not good test-takers, it makes graduates from OSU more attractive to potential employers.

Straka, who said he might not have gotten in with his 28, said he believes an OSU degree gave him a competitive edge in the job market — especially among Midwestern employers. Straka said he thinks the school’s rising admissions profile helped him get a position working for U.S. Sen. Todd Young, of Indiana, after graduation.

“Ohio State, today, is not the Ohio State your parents got into, and Ohio State — in terms of admission — is not the same Ohio State that (the class of 2017) got into.” — Tom Woodford, college counselor for Hilliard Darby and Hilliard Davidson high schools

Keith Gehres — director of outreach and recruitment Undergraduate Admissions, University Orientation and First Year Experience — said a test score below recent averages does not automatically disqualify someone from being admitted.

“We are not reviewing students based on an academic index,” he said. “Not every great student is going to excel on a standardized test. Just not like every great student may have had the resources to succeed in their high-school experience the same way as somebody else. That is why it is so important we engage in holistic review.”

Open enrollment

Tom Woodford, the college counselor for the local Hilliard Darby and Hilliard Davidson high schools, said the quest for most colleges has gotten significantly more competitive throughout his career.

“Ohio State, today, is not the Ohio State your parents got into, and Ohio State — in terms of admission — is not the same Ohio State that (the class of 2017) got into,” Woodford said.

Before the mid-1990s, OSU was an open-enrollment university.

Such institutions use noncompetitive and nonselective admissions processes, granting spots to students with high school diplomas or GED certificates, as long as spots are available.

A student takes a standardized test. Credit: TNS

Gehres said OSU did not accept every student prior to the end of open-enrollment in the ’90s, though it did not qualify admissions based on academic performance.

“It really was a first-come, first-serve process. In the mid-’90s is when we started that incremental shift and growth around a selective or competitive admissions process,” he said.

GPA and high-school ranking

Test scores are not the only rising benchmark making gaining admission to OSU so difficult.

Of the high schools that report rankings of their graduates, nearly two-thirds of those high school graduates enrolled at OSU were in the top 10 percent of their classes in 2016. In 2011, 55 percent were in that group, and, in 2006, it was 43 percent.

But the trend for OSU applicants to be highly ranked has effects on high schools’ decisions. Due to the increasing expectations of state universities that their students be at the top of their academic classes, fewer high schools are continuing to rank their students by GPA, according to admissions data.

While a student might have impressive test scores, such as Gaines, the senior at Walnut Hills, those who go to more rigorous secondary schools often fall outside of the top 10 or even top 25 percent GPA of their classes.

Nearly three-quarters of enrolled, incoming first-years’ high schools submitted class rank in 2006. In 2011, 65 percent did. Last year, less than half of enrolled first-years’ high schools ranked their students at all.

Woodford said ranking students can sometimes hurt them, though both high schools in his district still do it.

“If a student has a 4.3 (weighted) GPA and they are ranked 48th, some universities might look at that a little differently and have to look deeper into the curriculum in the school profile,” Woodford said.

He said his district continues to rank students because it allows prospective universities to see how students might do among other high-achieving classmates.

Gehres said students whose high schools do not use traditional class-ranking systems are neither advantaged nor disadvantaged in the application process, but that they still consider the ranking process to be a valuable tool for considering applicants.

For students whose respective high schools do not submit ranks, Gehres said OSU can make estimates, and use other relevant data.

“High schools provide tremendous information when they send us their profiles,” Gehres said. “Whether it’s a grade distribution, or average GPA, or deciles, quartiles, quintiles — whatever system they use — we are able to use that information to understand that a student would be estimated to be in the top 10 percent of their class, even if they don’t tell us the student is 20/200.”

More and more applications

Test scores and class rankings of prospective students have dramatically improved over the last decade, but OSU’s Columbus campus acceptance rate has remained relatively stable, hovering around 50 to 60 percent between 2012 and 2016.

What is changing is the number of students who are applying. In 2006, 18,286 students applied to the Columbus campus. This year, there were more than 52,000 applicants, Gehres said. Since the pool of applicants is getting much larger, the admissions department can be more particular with who ultimately gets a spot.

Students move into their dorms before Fall Semester 2016. Credit: Nick Roll | Campus Editor

Woodford, the high school counselor dealing primarily with college admissions processes, said the implementation of the Common Application is a major factor behind the flood of applicants. OSU began using it in spring 2013.

Between 2013 and 2015 alone, there was a 28 percent increase in applicants.

“As soon as Ohio State made the transition to the Common Application, they started seeing a spike in applicants,” Woodford said. “That’s why they are getting 50,000 applications (to review) now. It’s easy for students who are applying to Ivy League schools to also apply to Ohio State.”

Gender gap

Among traditional academic factors, things like personality qualities, geographic residence and racial status are also considered.

“When we go back to the diversity of our incoming class, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity and all of those different pieces — that’s a layer (to consider) as well,” Gehres said. “Not that we are basing decisions on that, but we want to make sure it is reflective of the type of student body we would expect to enroll.”

Though the total proportion of enrolled male and female students at OSU is almost equal, in seven of the past 11 years of available data, more men have applied to OSU, but more women have been admitted.

In fact, 2012 is the only year in which OSU accepted a larger percentage of men than it did women.

In 2015, 47 percent of male applicants were accepted, and 52 percent of female applicants were admitted that same year. In 2016, 12,620 women were accepted, while 11,645 men were admitted.

Gehres said that the patterns seen between gender and education is an issue that the U.S., as a whole, continues to grapple with.

“In the application process, I’ve seen analysis on female high school students who mature earlier and have more time to prepare for that college process,” Gehres said. “But there is not a simple answer (as to why this trend is occurring).”

Over the course of the past decade, each incoming freshmen class has surpassed its predecessor in terms of academic merit and other positive factors, Gehres said, though he noted that this trend is likely to plateau.

While nearly half of all incoming freshmen who submit ACT scores are placing themselves in the highest score range, and well over half of those who have available class rankings are within the top decile, there is limited remaining room to improve.

For Gaines, the high school senior from Cincinnati who always wanted to be a Buckeye, there is still hope.

If he makes it off the waitlist by June, he will be sporting scarlet and gray in the fall. If not, Gaines will still be studying engineering — except it will be at Case Western Reserve University.