Alex Brumfield, center, is one of a decreasing amount of students from the Appalachian region of Ohio to attend the university. She created a student organization at Ohio State to help students from the region transition to college. Courtesy of Alex Brumfield

“Congratulations for getting out.”

That’s the phrase Alex Brumfield has grown accustomed to hearing when she visits her hometown of Gallipolis, Ohio, a community of less than 4,000 on the West Virginia border.

The soon-to-be Ohio State graduate certainly deserves some form of congratulations for being accepted to a university that is enrolling fewer and fewer students from her area of the state.

She graduated as Gallia Academy High School’s valedictorian in 2014 with a 4.3 GPA.

But Brumfield doesn’t quite know what to make of the congratulatory phrase she keeps hearing. She isn’t comfortable with the notion that her hometown is an undesirable place to live.

“I think a lot of people, they feel like they’re stuck in Gallia County. They feel like they can’t leave and it’s almost like a failure if you don’t leave,” she said. “I don’t think it’s a bad thing if you don’t leave Gallia, but they all say it’s a big success if you get up and do something else.”

For the record, Brumfield — who is the president of the Community of Appalachian Student Leaders at Ohio State — did want to leave. It made absolute sense to pursue an education at a university with high admissions standards.

But Ohio State’s high admission standards, rising attendance costs, and increased selectivity are keeping talented high school students from Brumfield’s region and other areas across Ohio from attending the state’s flagship university.

Ohio State enrolls fewer students from Ohio’s Appalachian counties than it did a decade ago. It also enrolls fewer students from the 10 most populous counties combined.

The university’s in-state enrollment has remained stagnant over the past 10 years as Ohio State takes in a growing amount of out-of-state and international students.

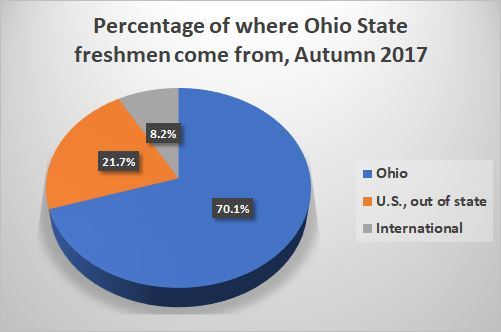

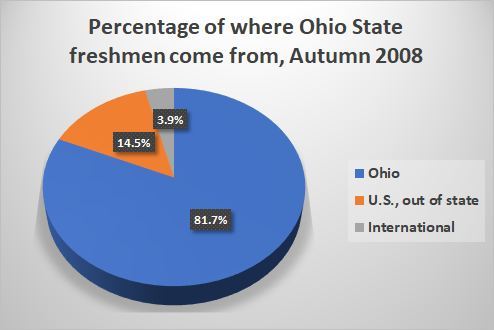

A Lantern analysis of Ohio State’s past 10 years of enrollment data shows Ohio high school graduates represent nearly 12 percent fewer incoming first-year students in 2017 than they did a decade before. In 2008, almost 82 percent of freshmen came from the Buckeye State, but in 2017 that number dropped to 70 percent.

Over the same period, this dip is paired with first-years from outside the U.S. doubling from 4 percent to more than 8 percent. Out-of-state freshmen jumped from 14.5 percent to almost 22 percent.

Keith Gehres, Ohio State’s director for outreach and recruitment, joined the university as an in-state recruiter in 2003, and while he said he has noticed several changes in the student body, none of them particularly alarm him.

He was instructed in 2015 by Ohio State’s Board of Trustees and University President Michael Drake to follow a strategic enrollment plan, which he called “the North Star in our recruitment efforts.” That “North Star” is guiding his office farther and farther from the state of Ohio.

“As the flagship institution and also with being charged with meeting all the various university enrollment goals, there’s a balance where we can’t only focus on in-state students,” Gehres said. “We’re focusing on out-of-state and students from around the world.”

The goal is for out-of-state and international students to account for 35 percent of the university’s incoming first-year class by 2020, Gehres said. In 2017, non-Ohio residents comprised 29.9 percent of the freshman class.

The shift in enrollment by the state’s land-grant university highlights the limited social mobility of young adults who grow up poor.

The Appalachian region of Ohio, which is composed of 32 counties primarily in the southeastern quadrant of the state, represents less than 7 percent of Ohio State’s undergraduate enrollment — and that number continues to shrink each year. A decade prior, that number was nearly 11 percent.

Additionally, the decreasing representation of students from Ohio’s most populated areas underscores the transformation of Ohio State’s student body.

Appalachia

Brumfield is one of the few from her high school and county who attend Ohio State. In 2014, the year she graduated from Gallia Academy High School, she was one of seven freshmen from her county to enroll at the university.

Brumfield said she never had an Ohio State recruiter come to her high school, something that her Community of Appalachian Student Leaders staff adviser Tiffany Halsell feels is representative of the university’s involvement, or lack thereof, in the region as a whole.

“No one wants to go to these Appalachia counties because in their minds I think we still have that bias about the population and the students and their capability about performing well at Ohio State,” said Halsell, who works as the graduate student services coordinator for human sciences.

The problems plaguing Gallia County impact large swaths of the region and limit the ability for talented high school graduates from the area to make their way to any college, let alone Ohio State.

Gallia County ranks in the bottom third of the state along with a majority of Appalachian counties for median household income and other economic indicators, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Cindy Graham has taught English at River Valley High School in Gallia County for more than 30 years after attending Ohio State and moving back home to complete college at the University of Rio Grande.

She said she has seen Ohio State turn its attention away from students from her school, adding that she has never seen an Ohio State recruiter at the high school during her tenure.

“I can’t tell you in 33 years of teaching where someone from Ohio State has reached out to come and present or even offer that,” she said.

Coming from southern Ohio’s Pike County, the underrepresentation and lack of recruitment of Appalachian students at Ohio State was personal for Lynaya Elliott, who created and now advises the Appalachian student organization. She said bridging the gap for students coming from lower-income counties or school districts is the role of the university, something she feels is not being done.

Lynaya Elliott, left, and Tiffany Halsell, advise the the Community of Appalachian Leaders student group at Ohio State. Matt Dorsey | Engagement Editor

“We are a land-grant institution. Thirty-two of your counties, beyond an extension center, [Ohio State] might want to invest in the populations and be a part of the solution for an economic upturn,” said Elliott, who also serves as the department manager for women’s gender and sexuality studies at Ohio State.

Both Brumfield and Elliott said the more than 50 students they work with have not seen significant recruitment effort from Ohio State.

“I haven’t heard many [students] say that they were recruited or anything,” Brumfield said. “I think it’s kind of the same story. Ohio State’s that great school that everyone wants to go to, but … I haven’t really heard much about recruitment and that kind of thing.”

While not speaking directly about Ohio State, Amanda Janice Roberson, a senior research analyst at the Institute for Higher Education Policy whose research focuses on the Appalachian region, said these low-income communities are often underserved. Colleges are hard-pressed to provide the resources these students need and don’t do enough outreach, she said.

“University leaders with disproportionately low Pell-enrollment at their institutions cited factors such as gaps in college readiness, budget constraints, high nonresident enrollments, and geographic isolation,” Roberson said in an email. “While these factors represent real challenges in attracting, retaining, and best serving low-income students, they can be overcome.”

Population centers

Of Ohio’s 10 most populous counties, six have recorded decreases of more than 10 percent in the number of graduating high school students who enrolled at Ohio State in the past decade. There are fewer Ohio State students from these counties combined and they represent a smaller portion of the undergraduate student body than a decade prior.

One county with a substantial decrease is Hamilton, Ohio’s third largest. Bordering the Ohio River in the southwest quadrant of the state and encompassing Cincinnati, the county is represented at Ohio State by 300 fewer students now than it was in 2007, and 168 fewer than in 2010, despite having recorded a population increase from 2010 to 2017.

In particular, school districts in areas facing economic distress have seen declines in the number of students who enroll at Ohio State. One such example is the Princeton City School District, which, in the early 2000s, regularly enrolled two dozen graduates as first-year Buckeyes each year. In the past decade, however, an average of 11 Princeton High School graduates have enrolled each year.

The trend follows changes in the area that Christina Grabel, a guidance counselor for seniors at Princeton High School, has observed in her decades living and working in the area.

“For many years there were a lot of more affluent families and homes in the Princeton area. Like with everything else, a lot of businesses started closing,” she said. “Princeton started bringing in less and less money, cuts were made. A significant number of teachers were cut in the district.”

Those cuts included the counseling department, effectively reducing it by half, leaving Grabel scrambling to meet the counseling needs of 388 seniors on her own. She said it has led to being constantly flagged down by students in hallways before school and maintaining correspondence with them on her own time through email.

While the financial struggles of Princeton have led to such overextended staffing situations, they also have made it challenging for students to view themselves as college-bound.

“Sometimes, kids are not getting the support they need at home, sometimes it’s because a lot of my kids are working 40-hour-a-week jobs,” Grabel said, describing why many Princeton students might struggle to find a path to college. “Lots of students are doing that. They come to school, they leave, they go to work, they work half the night long, they go home, they get a few hours of sleep and then they’re right back at it.”

A schedule like that leaves little time for a high schooler to make a visit to a potential college destination, let alone find the time to apply.

Princeton High School sophomore Sevara Djurakulova said she sees what Grabel speaks of among her classmates, noting that many lack two-parent households.

“They work at night and they come to school, so it’s really hard to get homework done,” she said of her fellow students.

Djurakulova came to Ohio with her family from Uzbekistan four years ago. With her permanent resident status, she would be considered an in-state student were she to enroll at Ohio State — her current first-choice for a college — but is grateful for one of the things contributing to the drop in the percentage of students coming from Ohio: the growing international student population.

“I like the community on campus. I like how it’s international,” she said. “All people go there from different places.”

Djurakulova, who attended the Day in the Life of a Buckeye event in March, said Ohio State is similar to Princeton in terms of having a diversity-rich population and is hoping a Russian friend of hers who also lives in her town will attend Ohio State.

A group of Ohio high school students toured the RPAC as part of Day in the Life of a Buckeye in March. Credit: Matt Dorsey | Engagement Editor

Shifts in where Ohio State students come from have occurred not just county-to-county, but also among school districts within each county. Ohio State’s own backyard, Franklin County, is an example of such changes.

Of the six Franklin County school districts which consistently send the largest numbers of graduates to Ohio State, only two — Dublin and Hilliard — have increased the number of students sent between 2007 and 2017.

Dublin City Schools has nearly doubled its presence on Ohio State’s campus, with 118 graduates enrolled in 2007 and 221 by 2017.

Columbus, Worthington and Upper Arlington’s school districts all had a smaller presence in 2017 on campus than they did in 2007, while Westerville’s enrollment has remained relatively steady across that time frame.

Columbus City Schools’ enrollment of first-years from the district fluctuated from 2007 to 2011, then declined sharply — from 130 students in 2011 to 57 in 2015, before steadily growing the past three years.

What Ohio State is doing

Ohio State is among dozens of selective colleges grappling with how to better serve underrepresented and low-income populations.

Roberson said colleges that have resources and support in place alleviate concerns for students when they arrive on campus and set themselves apart as institutions that show they are committed to educating all students.

“A strong institutional commitment to economic diversity and equitable outcomes and the availability of support systems on campus can attract these low-income students to colleges and universities,” Roberson said in an email.

While the numbers show decreases in many of the communities that Roberson alluded to, Ohio State has reiterated its support for in-state students by doubling down on the Land Grant Opportunity Scholarship, which now covers the full cost of attendance for two students from each of Ohio’s 88 counties. The scholarship previously was awarded to one student from each county each year and only covered tuition, not room and board.

I just think that the idea that you could get in— just [Ohio State] reaching out and saying ‘yeah, you guys can do it’ would be great, having someone come and talk and say ‘yeah, we would love to have you.’ —Alex Brumfield, fourth-year in sociology and criminology, and president of the Community of Appalachian Student Leaders at Ohio State.

Brumfield’s enrollment at Ohio State was made possible when she was awarded her county’s only land-grant scholarship.

Although Ohio State didn’t enroll any students in 2017 from two Appalachian counties, Harrison and Morgan, that is not because the university didn’t offer the scholarship to anyone from there.

“We haven’t always enrolled a land grant scholar from every county,” university spokesman Ben Johnson said. “Students make their own decisions about what to do after high school and where to attend college. All eligible students in a county could decline the scholarship opportunity.”

Ohio State also has increased its funding for the Young Scholars program, which is one of Drake’s primary focuses in unison with his 2020 vision.

His vision calls for an additional $100 million invested in need-based aid.

The Young Scholars Program has provided scholarships to more than 3,000 first-generation college students from the nine largest urban school districts in Ohio in the past 30 years who demonstrate a high financial need.

The university also froze in-state tuition and expanded Pell Grant coverage for aid recipients, a move that costs the university more than $11 million each year.

The impact those increased commitments will have on the university’s shrinking share of in-state students will be revealed over time.

While the university is working to expand resources to help students like Brumfield find their way to Ohio State, she said communication of those resources to high school students is key.

“I just think that the idea that you could get in— just [Ohio State] reaching out and saying ‘yeah, you guys can do it’ would be great, having someone come and talk and say ‘yeah, we would love to have you,’” Brumfield said.