When he arrived at Ohio State to play football in 2002 on a full-ride scholarship, Roy Hall had never heard of a Pell Grant. He didn’t know where the extra money his teammates received every quarter came from until someone told him halfway through his freshman year.

Hall, a South Euclid, Ohio, native raised by a single mother, saw his athletic abilities and full-ride scholarship as his way to get an education debt-free. With his father not in the picture and his mother working multiple jobs just to keep their home, Hall said being a student-athlete had plenty of benefits. However, being a full-time athlete on top of a full-time student was a tradeoff.

“Student-athletes don’t have freedom,” Hall said. “We are told what to do, when to do it, how to do it, when to go, when to leave, when to wake up, when to get dressed. You’re told everything.”

That lack of freedom is seen most clearly in a student-athlete’s demanding schedule, Hall said. The inability to work a part-time job on top of practices puts financial strain on some athletes, like Hall, who were already struggling to make ends meet. Finances were often still tight at home, despite being relieved of the burden of paying for school. That’s where Hall said the Pell Grant helped him and his family.

Former OSU wide receiver Roy Hall (8) runs with the ball during a game against Michigan on Nov. 18, 2006. Credit: Courtesy of TNS

Hall said many of his teammates at Ohio State would send their Pell Grant checks to their families to help out at home. For those that didn’t, the money went towards buying extra food, a new set of clothes or a pair of shoes. Regardless of where the money went, Hall said receiving a Pell Grant was a celebration for every recipient.

“Playing football in high school put me in a position to get a full athletic scholarship, but once you get there, having that day-to-day money on campus is the challenging part,” Hall said.

During his freshman year at Ohio State, the maximum amount a student could receive from a Pell Grant was $4,000 per academic year. Receiving a Pell grant, which one becomes eligible for based on financial need, kept some football players from having to go behind the NCAA and the school to get some extra cash, Hall said.

“What the Pell Grant does is it allows us to not have to do illegal things to make a couple extra dollars, to pay for an outfit or to pay for shoes or to pay for whatever it may be,” Hall said. “The temptation for the football player or the basketball player to sell a jersey or to take a check or cash from somebody illegally is there because they are struggling. They are struggling at home. What do you do when mom is living check-to-check, the lights aren’t on at home and you’re playing for this great university?”

When people think of student-athletes, images of game day and bronze trophies usually come to mind. So does a coveted full-ride scholarship.

The glory they hope to achieve on the field or the court is often supported in part by an athletic scholarship. The reality for many student-athletes, however, is that those scholarships do not cover all their needs. Many athletes need to rely on federal aid, such as the Pell Grant, to get by.

A Lantern analysis found that athletic scholarships are not the only form of assistance that these athletes rely on.

Nearly one in five student-athletes received a Pell Grant during the 2016-17 academic year, according to data obtained through an NCAA financial report.

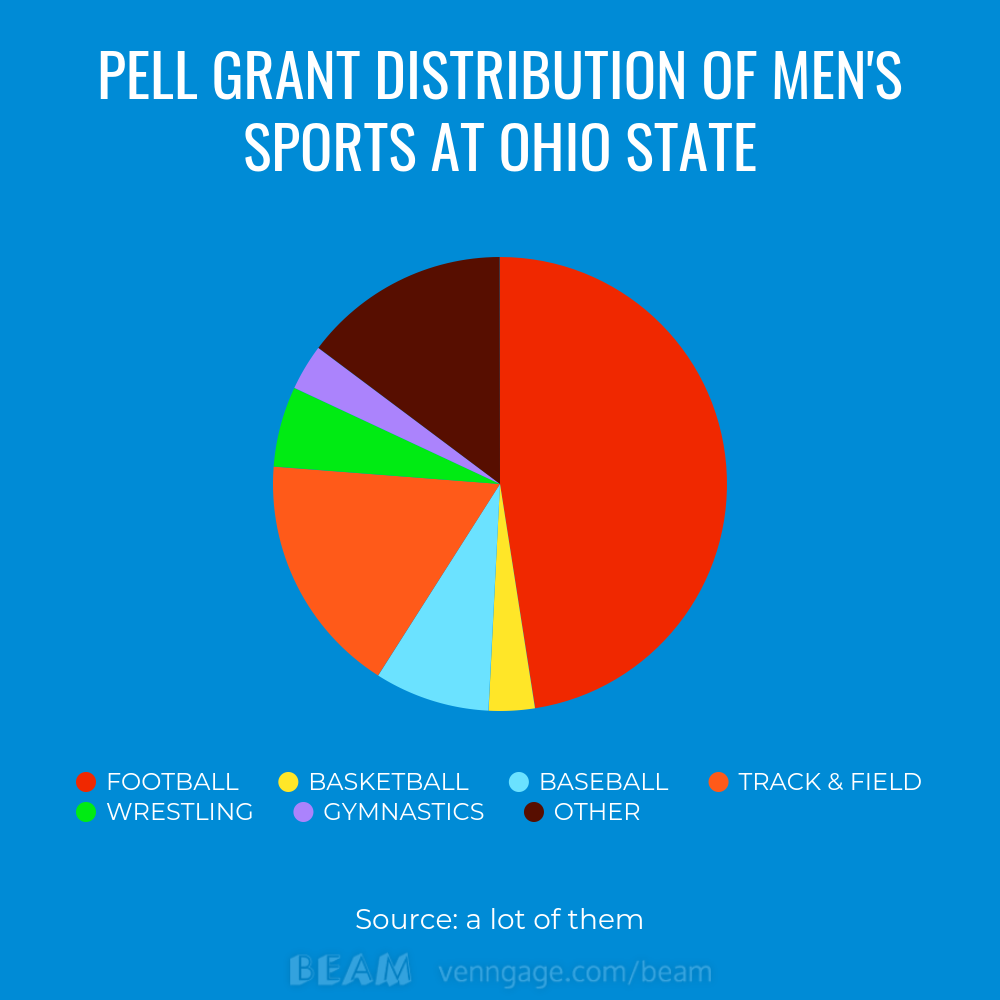

During the 2016-17 academic year, 47 percent of football players were on Pell Grants at Ohio State and 64 percent of them were on full-ride athletic scholarships as well.

In the high-revenue world of college sports, why are so many student-athletes in need of federal financial aid on top of athletic scholarships to make ends meet?

“What do you do when mom is living check-to-check, the lights aren’t on at home and you’re playing for this great university?” – Roy Hall

Athletic scholarships aren’t enough

A full-ride athletic scholarship, per the NCAA, covers the cost of attendance needed for a student to attend Ohio State, said Emily Haynam, a compliance officer with Student Financial Aid.

“The cost of attendance encompasses several elements, not just tuition and fees,” Haynam said. “Room and board would be included in there, an amount allotted for books and supplies, and an amount allotted for other expenses related to the cost of attendance.”

The current cost of attendance for an in-state enrolled student living on campus is $26,706 and for off-campus students it is $25,770.

Pell Grants, because they are a form of federal aid, have no effect on how a school awards athletic scholarships, which are at the discretion of the NCAA and individual schools, said Dan Wallenberg, associate athletics director for communications at Ohio State.

Pell Grants can be used as a buffer for what is not covered by an athletic scholarship, such as groceries, car payments and personal items.

Many athletes rely on Pell Grants to get by because their athletic scholarships often don’t cover enough of their expenses, according to Sara Garcia, a higher education policy analyst at the Center for American Progress.

“What you see is scholarships that cover tuition and fees and room and board, but students still have other costs of attendance,” Garcia said.

A 2010 report by Ithaca College and a national athletes’ advocacy group found the average “full-ride scholarship” Division I athlete ends up paying an additional $2,951 annually in school-related expenses not covered by grants-in-aid.

This shortfall represents the difference between educational expenses such as tuition, fees, room and board and additional costs not covered by scholarships, from campus parking fees to calculators and textbook access codes required for classes.

Because of the demanding schedule and expectations of college athletics, Garcia said most student-athletes don’t have the opportunity to work part-time jobs or participate in work studies. Pell Grants can fill those gaps.

This discrepancy in how much scholarship money each student-athlete is awarded is in part because of how athletic scholarships are awarded. There are two different ways of distributing athletic awards: headcount sports and equivalency sports.

Headcount sports distribute a specific number of full-ride scholarships to players on a given team each year.

For example, all NCAA Division I football teams can award 85 student-athletes a full-ride scholarship. Those scholarships cannot be divided up to give more athletes scholarships. Other athletes, such as walk-ons, will be ineligible for an athletic scholarship until the following academic year after athletes vacate the program’s scholarship capacity.

In headcount sports, such as football, basketball and ice hockey, a school can award any amount to athletes and it counts as a one full scholarship, regardless of the amount.

“Even if you give them less than a full grant, they’re going to count as a full grant,” Wallenberg said. “[Ohio State doesn’t] do that and we wouldn’t let that happen because it would just be punitive to the student-athlete at that point in time.”

Equivalency scholarships are different than headcount sports in that equivalency sports allow coaches to divide a single full-ride scholarship among multiple student-athletes. The NCAA still mandates how many scholarships there are to hand out, but the individual amount given to each athlete is determined by the coaches.

For example, the NCAA allows 9.9 scholarships be available for all Division I men’s soccer teams. If a player was allotted half of the cost of attendance by his coach, that player accounts for half, or 0.5, of a scholarship from the total 9.9 scholarships available. Same goes if a player is offered a quarter of a scholarship, that would count as 0.25 and go into the total 9.9 equivalency scholarships.

The amount of these scholarships will differ depending on if the athletes are in-state or out-of-state, due to tuition fees varying, but the proportion would remain the same.

“They can have partials and portions, but they can’t go over that 9.9 in their general allotment. Each coach is different in how they awarded their scholarships and their percentages,” Wallenberg said. “It could be based solely on their athletic ability, it could be athletics and academics, it could be contribution to the team.”

Since these scholarships are split among several athletes, full scholarships are rarely offered to every athlete who play on equivalency-scholarship sports. This can pose a problem for athletes who aren’t on a full-ride scholarship.

For example, there are 40 student-athletes on the Ohio State men’s track and field team. Because track and field is an equivalency sport, there are only 12.6 scholarships available, per the NCAA. While it’s possible that each athlete can receive a portion of a scholarship, there’s no way that every student-athlete could receive a full-ride scholarship under this model.

With 21 members, just over half of the track and field team is on a Pell Grant.

Ohio State breakdown

While student-athletes at Ohio State are statistically receiving more Pell Grants, a Lantern analysis found that Ohio State’s undergraduate student body, and other Big Ten schools, have a declining number of Pell Grant recipients since 2010.

Currently, in-state tuition and mandatory fees on the Columbus campus total $10,591, almost double the maximum Pell Grant award.

Of the 1,011 student athletes at Ohio State, 72 percent of them receive athletic-student aid. This includes summer school, tuition discounts and waivers and aid given to student-athletes that are inactive due to medical reasons.

At Ohio State, almost one in five student-athletes receive a Pell Grant , but the aid is not distributed proportionally among all student-athletes.

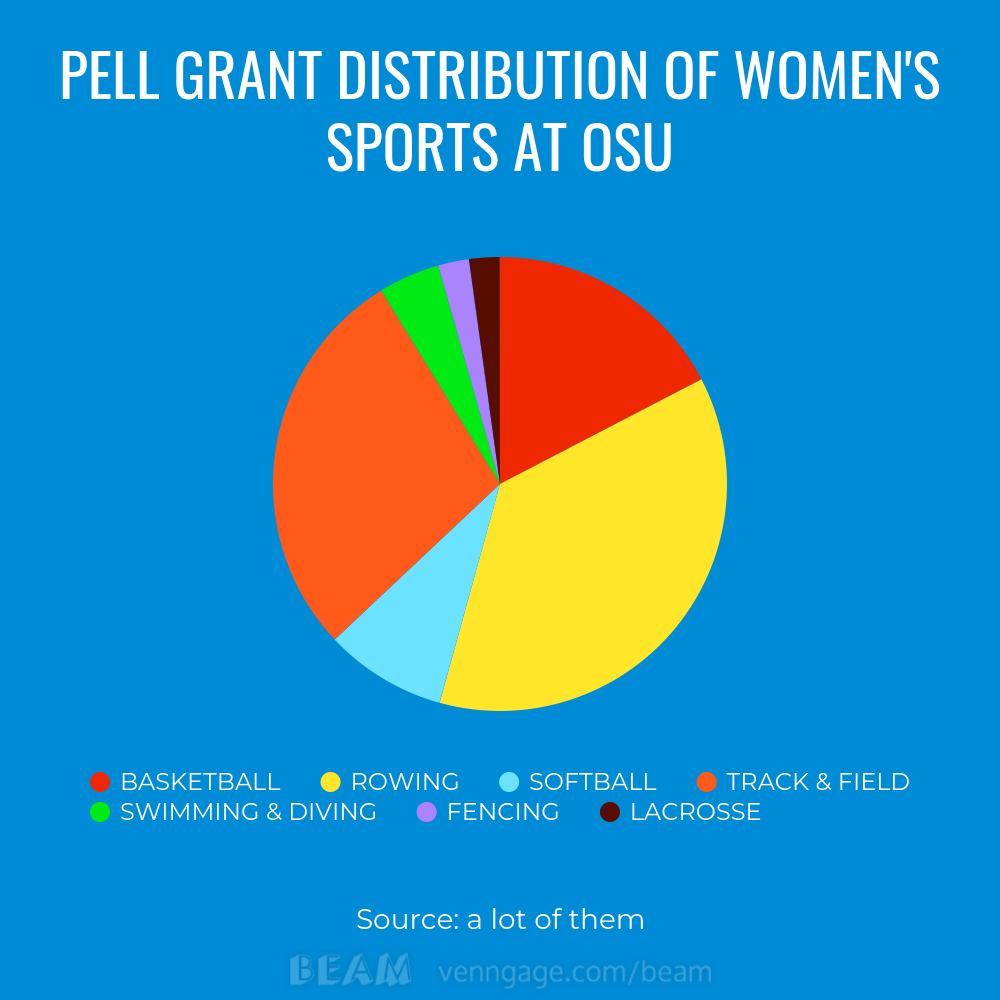

Female student athletes make up 45.6 percent of total student-athletes at Ohio State. However, they’re only receiving 28 percent of the Pell Grants allocated to student-athletes at Ohio State.

There are 14 women’s Division I sports at Ohio State, but Pell Grant recipients only come from seven of those sports. The most notable is Ohio State’s rowing team which received $86,206 in grants among 17 team members.

Of the nearly half-million dollars in Pell Grants awarded to Ohio State male athletes this year, almost half went to football players. Nearly one in four players on the men’s basketball team were Pell grant recipients and of the 16 women’s basketball players, more than half of the team received Pell Grants.

Field hockey, men and women’s golf, women’s gymnastics, women’s ice hockey, men’s and women’s tennis and women’s volleyball all had no Pell Grant recipients in the 2016 school year.

Male and female members of the cross country and track and field teams earned a combined $134,894 in grants, distributed among 34 participants.

Student-athletes and poverty

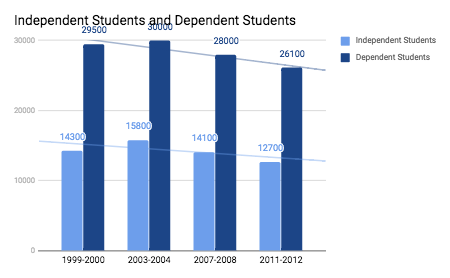

Over the last two decades, an analysis of Pell Grant recipients shows two striking trends. One is that the average Pell recipient is making less money than before. The other is that more Pell recipients are overwhelmingly from a minority background.

During the 2015-16 school year, 73 percent of dependent Pell Grant recipients had an average household income of less than $40,000. Thirty-eight percent had household incomes less than $20,000.

According to the Department of Education, the average Pell Grant recipients’ family income has been on the decline. During the 1999-2000 academic year, the average Pell Grant recipient had an annual family income of $29,500. By 2011-12, the average annual income has decreased by $3,400 to $26,100.

For a four-person household, that income was only $3,000 above the federal poverty line.

In addition to that trend in grant recipients, there are stark contrasts in the race breakdown.

The proportion of African-American students receiving the Pell Grant has increased by 22 percent from 1999 to 2012. Mixed-race students increased by 20.6 percent. In comparison, Hispanic students only increased by 5.4 percent.

This stark increase in African-American students receiving Pell Grants is consistent with increasing African-American athlete populations on Ohio State’s campus.

According to a Lantern analysis, the undergraduate African-American male population in 2016 was 1200 students, or just 2.6 percent. However, black men are overrepresented in athletics.

The football team is 53 percent African-American, men’s basketball is 76.9 percent, track and field is 25.6 percent and baseball is 5.2 percent. In 2016, almost one in 10 of the black males on campus were athletes.

Ramogi Huma, the executive director of the National College Players Association, believes the NCAA is not doing enough to lift student-athletes out of poverty.

Huma played Division I football at UCLA and started his organization while he was a student-athlete.

“We believe strongly that any player that qualifies should receive a Pell Grant . There’s a litmus test for that and there’s some players on some sports [teams] that don’t have full scholarships, many players are on partial scholarship,” Huma said.

Huma believes that the NCAA has a pattern of disenfranchising black athletes, with universities prioritizing wins over academics when so few of these men are becoming professional athletes.

“Only 2 percent step foot in the NFL and the NBA,” Huma said. “The vast majority, their most valuable time in their lives is in college, is in those four years economically but they’re not able to capitalize on that.”

Statistically, Pell Grants are not keeping up with rising tuition costs.

“You’ve seen a huge decrease in the buying power of Pell, so to speak, over the last decade,” Garcia said. “Now, a typical four year university, I think the Pell Grant covers less than 30 percent of tuition and fees and room and board.”

Some experts say that an increasing number of student-athletes points to a fundamental problem with the way NCAA sports are set up. Many prominent figures in the sports world have been critical of the lack of resources for student-athletes that come from poverty.

“In turn, these players are qualifying for tax payer’s dollars, the Pell Grants,” Huma said. “When you talk about where the Pell Grants go and why, they’re a very good resource for students that need financial assistance to get through college. But when it comes to big-time college football and basketball, Pell Grant money shouldn’t be necessary at all.”

Huma started his organization in 1995 after a teammate on the UCLA football team was suspended for accepting groceries that we’re left on his doorstep. Huma became an advocate for student-athletes while still playing football for UCLA and has continued his work throughout his life.

“It’s not just Ohio State. It’s the majority of Division I schools, and it brings up a whole other issue,” Huma said. “For us, our advocacy, we stand against any injustice for players of all sports, all races.”

Huma, and other critics of the NCAA, believe full-ride scholarships aren’t cutting it, especially for athletes participating in revenue sports such as football and basketball. This has been a hot topic in the media as of late, stirring up controversy among figures in the sports world.

Recently, the AP reported that NCAA President Mark Emmert said that college sports are “not in crisis” and that paying athletes is not the right answer.

“We’ve got these very serious issues which require serious change and they erode people’s belief in the integrity of all college sports,” Emmert said. “That’s a very serious problem and that’s got to be addressed and we’re doing that right now and… next year we’re going to have really meaningful change that makes this circumstance, if not completely go away, dramatically better than the problems that exist today.”

Hall said that sometimes the Pell Grant doesn’t even go to the student-athletes.

“Some of the student-athletes, just in my experience, weren’t even able to really use it for themselves as much as it was this is a money we can get per quarter or per semester that we can just send home,” Hall said. “You have the student-athletes that didn’t have to send it back home, but we needed it for clothing or additional food or whatever it was that was necessary at the time obviously from a day-to-day living standpoint.”

The vast majority of athletes who play their sport at the collegiate level will never make it to the professional leagues. The NCAA estimates that less than 2 percent of all college football players will ever play in the NFL. Hall was one of the few who made it.

After playing for Ohio State, Hall went on to play several seasons in the NFL and the United Football League. During that time, he also helped start the Driven Foundation with former teammate Antonio Smith, an organization that uses the pair’s personal experiences to mentor and serve at-risk communities.

In the years since Hall donned scarlet and gray on the field, he said college athletes today have more at stake, with greater pressure to perform. They realize they’re more than just athletes. They realize they need more from their education. They realize the pressure to take care of their bodies, as well as their families back home.

“With access to information and with these student athletes having gone through it, positioning themselves and educating themselves on how to defend and fight back against the likes of the NCAA and whatever it may be,” Hall said. “There’s going to be a lot of lawsuits, a lot of fighting until the rules start to change until the value of the student athlete is increased.”

Hall said the misconceptions surrounding student-athletes, that their full-ride scholarship makes them spoiled or that there’s no way an athlete of that caliber could be struggling, makes it hard for people to see the real problems facing these athletes. Athletes, he said, are seen as dollar signs and players on a field.

“Right now, it’s almost watered down to just your worth as paying for this education,” Hall said, “but the value that they’re generating for our university is much, much greater than the value of just that education.”

To help student athletes succeed, Hall said there needs to be a top priority on setting them up to be successful after they graduate. Hall said the answer might not be paying student athletes, but will more likely come in the shape of more aid for current students and helping them financially after they leave school.

“The one thing that’s different with the United States right now is you have to evolve with the times,” Hall said. “And if you don’t evolve with the times, you will get left behind.”