A delicate balance:

Despite steps toward affordability, college costs remain a challenge for low-income students at Ohio State

by Emma Scott Moran

This story was produced in Emma Scott Moran’s role as Patricia B. Miller Special Projects Reporter.

Between taking 13 credit hours, working as president of Pride OSU and holding a dining services position, Renae Cloutier keeps busy.

Cloutier, a third-year in math education, manages a delicate balance of school, work and extracurriculars to keep her finances afloat. Coming from a low-income background, Cloutier said keeping up with these responsibilities and making ends meet can be difficult.

“I didn’t have time to do the work that I had to do, but I couldn’t change anything about that, ’cause I need the money to eat,” Cloutier said.

(Left) Renae Cloutier, a third-year in math education, said she was lucky to have a second source of income outside of Ohio State when campus closed due to COVID-19. Credit: Courtesy of Renae Cloutier

(Right) Owen Watkins and his family write Ohio with sparklers on a trip to Buffalo. Credit: Courtesy of Owen Watkins

Before spring break, Cloutier split her time between a student assistant job at campus dining location Curl Market and a consultant position at insurance company Equitable, working about 25 hours a week total.

According to a fall 2019 Ohio State statistical summary, more than 13,000 students earn money working campus jobs, and for some, these earnings are necessary for them — and even their families — to get by.

“Some students on this campus work nearly full-time jobs and then send a chunk of their money back home to their families,” Vincent Roscigno, a sociology professor at Ohio State, said. “They’re not just paying for college. They’re also helping their families, which is an amazing burden for any 18-year-old.”

For low-income students who depend on regular weekly shifts, campus closures in response to the coronavirus are taking an especially hard toll. For Cloutier, Curl Market was included in those campus closures.

“I just lost the source of 90 percent of my income,” Cloutier said. “I had no idea what I was gonna do, ’cause I wouldn’t have enough money to pay rent, buy groceries — and all the stuff on campus is all shut down, so there’s just nothing for me.”

Left scrambling for solutions amid a pandemic, Cloutier said she feels lucky to have her job at the insurance company as an alternate source of income, as some do not have a contingency plan.

“Now that I’ve lost my main job, my second job has increased my hours, which is good, but a lot of people don’t have that,” Cloutier said. “And while everything was still developing, I didn’t know if I was going to be able to work enough hours at my second job to be able to support myself.”

Cloutier is one of thousands of students at Ohio State who could be classified as low-income, meaning someone whose family’s taxable income for the previous year did not exceed 1.5 times a poverty level amount set by the U.S. Department of Education, according to the department’s website.

Just how many students fit into this classification is not clear, but there are more than 9,300 students who receive a Federal Pell Grant — a form of aid that does not need to be repaid and is usually given to undergraduate students who demonstrate exceptional financial need.

Though COVID-19 has created a new crisis, being a low-income student at Ohio State has always been challenging.

Ohio State offers many resources to help these students, such as financial aid programs, reduced textbook and course fee costs and support finding scholarships, but juggling responsibilities and expenses, as well as accessing support systems, can still be a challenge.

Nontuition expenses, which can include necessities such as housing, food, books and child care, are generally not covered by financial aid and can push students over the edge of their budget.

Aside from the financial stress of a low-income status, other social issues, such as race and gender, can contribute to these students’ college experiences.

The university works hard to ease the strain for low-income students by taking a comprehensive approach, establishing numerous programs and initiatives to attract, support, retain and graduate students from underrepresented populations, university spokesperson Ben Johnson said in an email.

“Ohio State is committed to access, affordability and excellence, and [University President Michael V. Drake] has made increased college affordability one of the cornerstones of his time as president,” Johnson said.

Despite these measures, attending Ohio State can be expensive or out of reach for low-income students and requires a careful mix of student aid, job earnings and grit to counter the mental and financial costs.

Ohio State’s Columbus campus tuition, which includes instructional and general fees, varies depending on the academic year a student enrolls. For the 2019-20 academic year, in-state first-years’ and transfer students’ tuition is $11,084 per year, while out-of-state first-years and transfers paid an estimated $32,061 per year, according to Ohio State’s undergraduate admissions website.

For students in the 2019-20 cohort, standard housing rates ranged from $3,371 to $4,329 per semester, according to Ohio State’s housing website, and students are required to live in university housing for their first two years.

Dining plans ranged from $1,976 to $2,025 per semester for the 2019-20 cohort of Columbus campus students, according to Ohio State’s dining services website.

In total, attending Ohio State could cost up to $23,792 for in-state students and $44,769 for out-of-state students — not including the other expenses such as food and books — and some say the university could be doing more to help with the cost.

Lack of Affordability

There is room for growth in terms of affordability at Ohio State, Eleanor Peters, assistant director of policy research at the Institute for Higher Education Policy, said.

“Ohio State University has some work to do on improving affordability and really making sure that they are targeting their need-based financial aid toward students with the most financial need and that those financial aid programs are addressing students’ tuition and their nontuition costs,” Peters said.

In the 2019-20 academic year, 61 percent of the institutional aid Ohio State awarded to students was need-based. However, according to Peters’ research with her colleagues — “Inequities Persist: Access and Completion Gaps at Public Flagships in The Great Lakes Region” published on the institute’s website — this is not enough.

In her publication, Peters defines affordable universities as those that give 75 percent of their aid based on need.

This 75-percent criterion makes clear that a significant majority of institutional aid should be need-based given the challenges low-income students face, Peters said in an email. Despite the pressures institutions face to use merit-based aid to attract more well-off students, some institutions do prioritize access for low-income students by meeting this benchmark, Peters said.

As a public flagship university, Ohio State is one of the most well-funded and prominent institutions in the state and has an obligation to serve students of all backgrounds, Peters said.

“It’s really important that we ensure that all students, regardless of their background, have access to [public flagship universities] because they’re most likely to set them up for success, and also because the institutions are mission driven to do so,” she said. “We’ve seen that low-income students and students of color don’t necessarily have the same amount of access as their more affluent peers.”

Inaccessibility of resources

The structure of public institutions can make it harder for communities of color to ask for help, Carlos Gabriel Kelly, an English Ph.D. candidate and co-executive of the Latinx Space for Enrichment and Research — a program that aims to provide resources, mentorship and guidance to help students from Latinx and other historically underrepresented communities get to college and stay in college — said. Roscigno said simply not knowing who to ask is a factor in this issue.

“I think it’s hard for any student to figure out what to do if they’re in academic trouble or financial trouble on this campus because it’s such a big campus,” Roscigno said. “There are so many offices all over the place. I think it’s more intimidating for low-income and first-generation students to have to grapple with bureaucracy that’s so big.”

Race and gender are huge factors in how people experience low income, Gabriel Kelly, who specializes in Latinx and gender studies, said. Gabriel Kelly is a first-generation Mexican American and comes from a low-income background himself.

“Women of color — I don’t know firsthand — but I know my colleagues have told me they have very, very, at times, toxic experiences in regards to students paying attention to them, or them being respected for their knowledge, or their emotional and mental labor being honored or being respected. And so is it worth it financially? Perhaps. Is it worth it mentally? That’s another question,” Gabriel Kelly said.

When budgets tighten, food is often one of the first expenses students forego, Gabriel Kelly said. Food insecurity is one of the largest problems he sees among his peers, he said.

“When it comes to low income, sometimes you may have to make decisions between food or books, where something has to be sacrificed. I know many colleagues who have gone through this, or they had to make decisions whether they were gonna eat, or whether they were going to pay rent, or pay their phone bill — and the spectrum is big in that regard,” Gabriel Kelly said.

Cloutier said she faced this issue when she wasn’t paid for a month after winter break because of Ohio State’s biweekly payroll system.

“I was making literally no money for, like, a month. And so during that time I ended up going to my major’s food pantry,” Cloutier said. “I got food there, which was really helpful. But I still just didn’t eat a couple of meals, kind of like a one-meal-a-day thing. And then I got food from work too, which is why I’m working at Curl because you get a free meal every shift.”

Burden of nontuition expenses

Nontuition expenses can be incredibly taxing for low-income students, Peters said. When students don’t have the resources to cover costs such as housing, they’re forced to make “unacceptable” decisions about how to make ends meet, sometimes jeopardizing their ability to be successful, Peters said.

Ohio State maintains a policy that began in 2016 that “all unmarried, full-time students within two years of high school graduation must live on campus for their first two years,” according to its undergraduate admissions website.

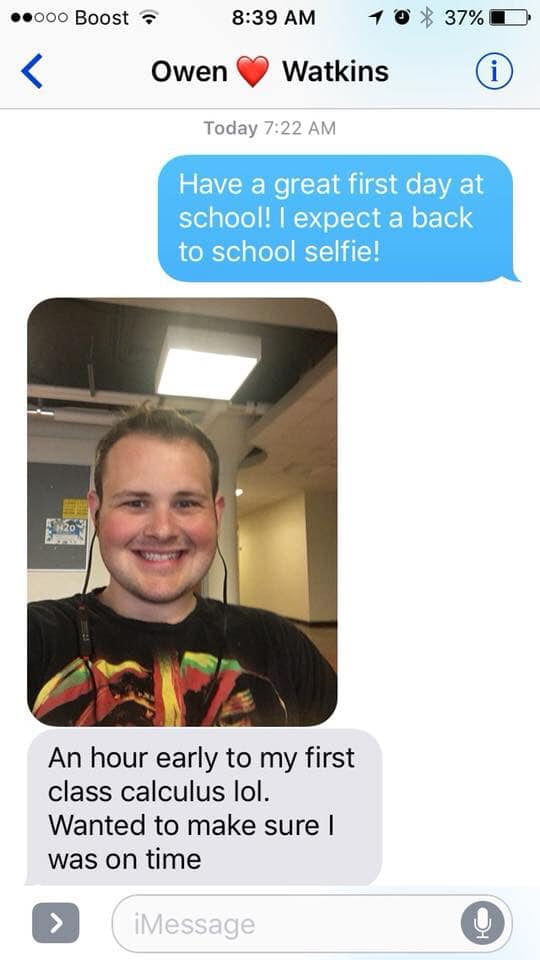

Owen Watkins, a third-year in chemical engineering and Pell Grant recipient, said absorbing the cost of housing and a dining plan was difficult during his first two years at Ohio State.

“I was spending about $20,000 a year when I was in OSU housing. When I was no longer in OSU housing, it dropped to, like, $10,000. That is so much more affordable for some son of a waitress,” Watkins said. “I feel like if [Ohio State was] really trying to give this whole inclusivity so that poor students can get that full college experience, then they would just drop how expensive it is to live on campus.”

Roscigno said there are well-researched benefits to living on campus, but that he feels torn on this debate. Though he said he understands housing is expensive, being on campus can be “the best thing that could happen” to students in their college experience and may increase the likelihood of graduating.

“I wouldn’t want our dorms full of more advantaged students who can take part in extracurricular activities and clubs on campus and stuff like that, and on the other hand, have all of our low-income, first-generation students off campus, not engaged in campus life,” Roscigno said.

Cloutier said that despite living on campus, she still felt limited in the extracurriculars she could participate in as a first-year because of her rigorous work and school schedule.

“I was in, like, three other clubs for at least the first semester or so before I had to start working. And once I started having to work, like, 20 hours a week, I can’t be in more things than one ’cause I just don’t have time. Either I’m in class or I’m working after class,” Cloutier said.

Cloutier said that although she understands the reasoning behind first-years being required to live on campus, she thinks second-years should be exempt from this requirement.

As president of Pride OSU, a student organization that provides a safe and open community for LGBTQ students, Cloutier said she has noticed a discrepancy in the cost of gender-inclusive housing. Transgender students are much more likely to not get support from their parents or have the money to pay for gender-inclusive housing in the first place, Cloutier said.

“You want them to find a community, you want them to be engaged in campus and that’s great and I support that, but two years is just so much money that I couldn’t afford and I just had no choice in it,” she said. “There is no inexpensive gender-inclusive housing. All of them are the top prices for dorms.”

According to previous Lantern reporting, gender-inclusive housing is only available at the highest housing rate.

Despite these challenges, the university has made efforts toward more affordability initiatives over the course of Drake’s tenure, including offering scholarships, reducing costs and creating support networks.

Scholarships, grants and financial aid programs

A major step toward improved affordability came with the fall 2018 launch of the Buckeye Opportunity Program, which covers the full cost of tuition and mandatory fees for all Pell-eligible Ohio residents enrolled at the Columbus campus, including transfer students, Shanna Jaggars, assistant vice provost of research and program assessment in the Office of Student Academic Success, said in an email.

According to Ohio State’s website, starting spring 2019, the university committed up to $3 million a year in additional financial aid to meet this goal. The award closes any tuition gap remaining after Pell Grants, Ohio College Opportunity Grants and other grants and scholarships are awarded, Jaggars said.

The maximum Pell Grant amount can change year to year, with the 2020-21 academic year having a $6,345 maximum award, according to the Federal Student Aid website. How much a student receives depends on their expected family contribution, the cost of attendance at their institution, their position as a full-time or part-time student and whether they attend school for a full academic year or less, according to the website.

Scholarships, such as the Young Scholars Program scholarship, the Stadium Scholarship Program and the Land Grant Opportunity Scholarship, are also valuable resources for low-income students, Jaggars said. In 2017-18, the LGOS was expanded from covering tuition and fees to including the total cost of attendance, as well as including two incoming freshmen from every Ohio county, amounting to 176 scholarships each year, Jaggars said.

According to Ohio State’s 2020 financial plan, the President’s Affordability Grant program, which has budgeted $25 million to support more than 15,000 low- and moderate-income students from Ohio, will also be expanded this year.

According to the plan, in fiscal year 2020, the university will invest more than $40 million into the Buckeye Opportunity Program, President’s Affordability Grants and the LGOS.

Watkins said he was able to navigate the process of obtaining financial aid with the support of the university, which found and compiled a list of grants and loans for which he was eligible after he submitted the Free Application for Federal Student Aid.

“OSU found them for me. I didn’t have to go looking around because I didn’t know those existed,” Watkins said. “They found me scholarships, gave me grant money, reduced my tuition cost for being an in-state student, and they’re giving me a good degree in one of the best engineering schools in the state. I definitely appreciate all that. But there are definitely places where they could look to improve.”

Reducing cost of materials and course fees

The university has also reduced the cost of textbooks by offering grants to support faculty in adopting low- or no-cost materials in their courses, thus saving students money, Jaggars said. Textbook costs vary depending on the courses a student is taking, but even a single textbook can cost $300 in some cases.

The program, which launched in 2015, is projected to save students a total of $8.5 million by the end of the 2019-20 academic year, Jaggars said.

In summer 2019, the university piloted a bulk-discounting program in which faculty can assign a heavily discounted commercial digital textbook to their students, Jaggars said. The pilot covered 21 courses, saving students about $288,000 total, while the expanded fall 2020 and spring 2021 pilots will cover 92 courses, saving students an estimated $2 million.

Ohio State also began providing every incoming undergraduate student with an iPad starting fall 2018, allowing equity in technology access for all students, including lower-income, through the Digital Flagship program, Jaggars said.

In spring 2019, Ohio State removed 70 percent of all course fees — previously used for educational costs such as laboratory sessions and specialized materials — impacting thousands of students across a broad spectrum of studies, according to an August 2018 university press release.

However, this reduction does not affect lab-heavy courses, such as biology, chemistry or physics, nor third-party costs, such as first-aid training.

Admissions and financial planning

Although Peters said Ohio State can improve in terms of affordability she also said Ohio State provides an accessible post-secondary education in many ways.

The university upholds an equitable admissions policy by not accepting early decision applications, nor considering students’ demonstrated interest, usually indicated through campus visits, in the admissions process. Both of these policies can disadvantage students who may not have the same access or know-how as more affluent peers, Peters said.

Admitted low-income students can be reimbursed for travel costs related to campus visits, Jaggars said.

Students are also supported through the Ohio State Tuition Guarantee, launched in 2017, which allows families to more easily plan the financing of a four-year education, Jaggars said.

“The guarantee ensures that in-state tuition and mandatory fees are frozen for four years for each entering freshman cohort,” Jaggars said. “This provides students and families with the consistency and predictability needed to fully assess all affordability options.”

The spring 2018 launch of Drake’s Time and Change strategic plan also took steps toward removing financial barriers faced by low-income students while attending or planning to attend Ohio State, according to the plan’s website.

The plan aims to enroll more talented low- and moderate-income students; improve affordability, first-year retention and four-year graduation rates; and reduce student debt, according to the plan’s website.

The university intends to accomplish this through outreach programs targeting low- and moderate-income prospective students, analytical identification of students at risk of dropping out and an improved students-to-academic advisers ratio, particularly for underrepresented populations, according to the plan’s website.

Ohio State also strives to improve support programs by using information gathered from the Second-year Transformational Experience Program, designing a new financial aid policy for low- and moderate-income students and crafting more scholarships for high-talent, high-need students, according to the plan’s website.

Finding a support system

Roscigno said some of the best resources on campus are found in the peer mentorship programs and social organizations, where students can find peers who relate to their experiences.

Clubs like Buckeyes First, which supports first-generation Ohio State students, give students a place to share their experiences, find support in an accepting environment and have a voice on campus, Roscigno said.

“There is a general reluctance for people to have to approach a stranger and say, ‘Help. I’m in trouble.’ It’s a hard thing to do, and first-generation, low-income students are very proud,” Roscigno said. “They worked amazingly hard to get here in the first place and they want to fit in.”

Students facing food insecurity, an issue that burdens many low-income students, can take advantage of the food pantries created by the student-run Buckeye Food Alliance. According to its website, BFA’s pantries are available to anyone with a BuckID and are located in Suite 150 of Lincoln Tower and at Saint Stephen’s Episcopal Church, located at the corner of West Woodruff Avenue and North High Street.

Students facing food insecurity can take advantage of the food pantries created by the Buckeye Food Alliance. Credit: Paige Reynolds | Lantern Reporter

The path toward an inclusive, accessible and affordable school will take efforts from several areas in the university, Roscigno said.

“I think it’s going to take a combination of university policy but also on-the-ground networking and inclusion to make it easier,” Roscigno said. “I think there are good actors in this university who really want to hear what the needs are of first-gen and low-income students, and they’re trying to figure it out. But this is a big machine, this university.”

Roscigno said some of these “good actors” are in the Office of Student Success, First Year Experience program and Office of Diversity and Inclusion, where staff members are constantly trying to figure out how to improve the support systems provided for students.

“We have mechanisms that are trying to make sure they’re successful once they get here,” Roscigno said. “It’s not perfect by any stretch of the imagination, but I think the energy at different points in the university from the very top, our president, to different centers and offices at the university are constantly in conversation trying to figure out how to make it better.”

But sometimes, these mechanisms don’t account for unforseeable factors.

“Pulling the rug”

Cloutier said there are times when her academics have suffered at the expense of making enough money to support herself. The weeks leading up to breaks are challenging, as they are often exam-heavy, and she said she simultaneously makes up for lost hours by doubling up on shifts.

“It gets kind of tight sometimes, especially around breaks when I’m missing a bunch of shifts because then I really have to either dip into my savings or really stretch myself out and not be able to buy things sometimes,” Cloutier said. “If you’re going to cut out a week’s worth of work, you have to give me some way to make that up, you know?”

The expensive and arduous process of moving out during breaks can be difficult to endure, especially for an out-of-state student, like Cloutier. At times, Cloutier was unable to relocate in such a short time frame and forced to find other living accomodations, she said.

“I ended up just kind of being homeless for a lot of the breaks while I was in dorms. I’m lucky that I had friends who were a year or two older than me who lived off campus that were fine with me crashing at their place for a week,” Cloutier said. “But I can’t imagine what it would be like if you were out of state and you don’t have friends who live off campus ’cause you just have nowhere to go.”

The weeks leading up to a new semester can also be stressful for low-income students. Peters said she has seen confusion among students regarding eligibility requirements for different types of aid, as small changes in one’s financial situation make impactful, sudden adjustments to their financial aid packages.

“We heard from students that this pulls the rug right out from underneath them if they’re counting on a certain amount of financial aid to carry them through a year or a semester and they realize right before the semester starts that that aid isn’t going to actually come through,” Peters said. “One student who we spoke with, his expected family contribution changed by $1 between his junior and senior year. That $1 change actually meant that he lost out on approximately $6,000 in financial aid.”

Renae Cloutier, a third-year in math education, works to balance two jobs, extracurriculars and school to make sure ends meet. Over 13,000 Ohio State students work on campus and for some, it is a necessity in order to get by. Credit: Courtesy of Renae Cloutier

When the scales tip

Cloutier is currently facing a different financial aid challenge than what Peters describes, though just as impactful. Her largest scholarship, the National Buckeye Scholarship for non-Ohio residents, lasts only for eight semesters.

Having switched majors from physics to math education a year and a half into college, she will not graduate within that time frame.

Without the additional $13,500 in aid lowering her $20,000 out-of-state fee, Cloutier said she cannot afford to keep attending Ohio State.

“I have mixed feelings because I really do like it here. I have really good friends. I love the people I live with and I liked my classes and all that kind of stuff. And it kind of sucks to know that I made a decision when I was 18 that costs me thousands of dollars and there’s nothing I can do about it,” Cloutier said.

Next semester, Cloutier will enroll and begin completing her degree at Temple University in her home state of Pennsylvania, where tuition costs will be lower.

“I’m not sad about going to Temple, but I am sad about having to leave and being 18 and not knowing what was going to happen,” Cloutier said. “I literally could not afford to have switched my major. I can’t afford it. I have to switch schools because I switched my major.”