The front page of The Lantern Oct. 11, 1918. Despite campus closing Friday, Ohio State played its football game against Denison Saturday. Credit: The Lantern Archives

In the fall of 1918, influenza was making a deadly comeback in the U.S.

Four years and three months into the world’s first industrial war, America saw its deadliest month in October caused not by the machine guns, landmines or constant shelling, but by a virus. The flu spread rapidly, devastating entire military camps, sweeping through cities, and killing the young and healthy disproportionately. More than 20 million people died during World War I, but the virus would kill even more — about 30 million more — in hospital beds around the world.

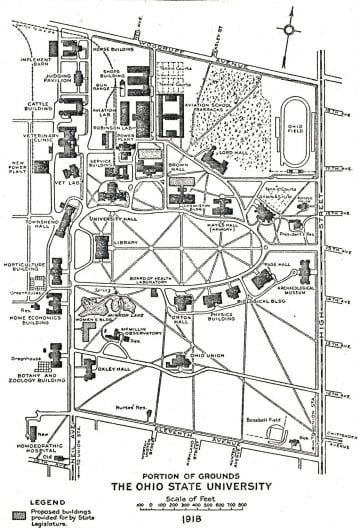

Before Ohio health officials ordered all public places, including universities and schools, to close down Oct. 11, 1918, the few murmurs of influenza at Ohio State were hopeful and ignorant.

A Lantern article a few days before reads, “Today’s good news from the surgeon general’s office informs us that Spanish influenza is losing its ‘grip.’ Comforting, indeed.”

Four days later, Ohio State administrators closed campus at 6 p.m. and all non-military students were sent home and told to check their local newspapers for when they could come back, according to Lantern archives.

“The situation in the University as to influenza is not alarming. The disease is, however, spreading throughout the state,” John J. Adams, acting university president, wrote at the time.

The Lantern published a letter from Dr. Emery Hayhurst, a department of public health and sanitation official, that pleaded with students to take every precaution against the disease.

“The disease is acquired through the nose and mouth and is spread chiefly by the secretions which come from these orifices. Hence to stop the spread it is necessary to stop the exchange of these secretions,” Hayhurst wrote.

Hayhurst advised against kissing and touching, using the same drinking cups or eating utensils, and to stay 5 feet away from others.

Although campus closed Friday, Saturday’s football game against Denison went forward with permission from the university’s Director of Student Health Dr. H. Shindle Wingert.

In a statement in The Lantern, Wingert said if the game’s spectators were “distributed throughout the stands as much as possible and at the same time being in the fresh air,” he could see no reason “why the game should be prohibited.”

Students and staff were told to use antiseptic sprays and gargle saltwater to stop them from getting sick. Wingert wrote in the university’s 1919 annual report that he hoped these preventative measures would let the university escape the epidemic that was “raging” in other parts of the country.

But on Sunday, Oct. 13, 1918, “the influenza epidemic invaded the student body,” Wingert wrote in his report.

The first cases on campus occurred among those in the Students’ Army Training Corps. The corps was organized in the summer of 1918 and taught military and aeronautics courses to male students.

The beginning of the training corps aligned almost perfectly with influenza coming to campus.

The Students’ Army Training Corps hospital where military students with influenza were treated on Ohio State’s campus. Credit: Ohio State Archives

In the annual report, University President William Oxley Thompson wrote that the onset of the influenza outbreak and the start of the training corps “proved a most unfortunate circumstance.”

Little attention was given to preparing the 20-bed hospital at the army barracks with the equipment and supplies it needed to take care of sick students. Wingert wrote that when the flu had reached the campus in full force, the hospital was completely overwhelmed for days.

Although the death rate was low, “the sick list was large and the interruption was serious,” Thompson wrote.

About 400 men became sick and shipments to the university of uniforms, bedding and equipment were delayed, according to the annual report.

Globalization is a friend to the flu

The war context is important to understand how the flu epidemic spread across the globe, Jim Harris, an Ohio State lecturer and historian studying infectious diseases and public health in the early 20th century, said.

Harris said the first cases of influenza were reported in March 1918 at Camp Funston in Fort Riley, Kansas. An army cook was hospitalized with a high fever and in a matter of days, the virus spread to more than 500 soldiers. By the end of March more than 1,000 soldiers at the camp had been hospitalized with the flu and 38 soldiers died after developing pneumonia.

The war amplified the spread and lethality of the flu.

Harris said the flu spread rapidly to the coasts and then to Europe as troops were moved from one military installation to another.

Factories making materials for the war effort couldn’t shut down, making them hotspots for the disease to spread among workers, he said.

Hospital systems were strained because most skilled doctors and nurses were overseas treating wounded soldiers, Harris said, “which just likely exacerbated the number of people who were infected, which in turn exacerbates the enormity of the death toll.”

“Globalization is wonderful. There are lots of great things of globalization,” Harris said. “But it also means that diseases can spread more rapidly and abruptly and you need to be more careful to contain them.”

The flu and the rise of public health

In 1918, cities restricted public gatherings, closed public spaces and either recommended or mandated that people wear face masks, Harris said.

During the 1918 influenza outbreak, street car passengers in Seattle, Washington were required to wear face masks. Credit: The Library of Congress

The response to the flu is not dissimilar to how states have responded to COVID-19.

Gov. Mike DeWine closed non-essential businesses and restaurant dining rooms. He and Director of the Ohio Department of Health Dr. Amy Acton have recommended people cover their mouths and noses when in public and to stay at least 6 feet away from others.

There are similarities between the response to COVID-19 and other diseases, Amy Fairchild, a public health historian and the dean of the college of public health, said. Fairchild is also the chair of the safe campus and scientific advisory subgroup for the post-pandemic operations task force, which is charged with returning operations back to campus once COVID-19 “has been deemed contained,” according to a university press release.

“It’s a predictable, historically recurrent story that we — not just as a nation, but as a globe — we can get alarmed at particular moments in time at the outset of epidemics,” Fairchild said.

Being alarmed means a response will be aggressive to try and control the spread or effects of a disease and public health funding increases, Fairchild said. However, when the disease begins to wane, so does funding.

“What it really speaks to is almost two centuries now of chronic inattention to public health, except at moments of agitation and alarm about particular outbreaks,” she said.

A lesson learned from the response to the 1918 flu epidemic is that social distancing works, Fairchild said. The communities that instituted social distancing policies early and sustained them over the course of the epidemic had lower death rates. The economies of these communities also recovered faster.

“There is no such thing as a cheap pandemic. It’s going to be economically devastating,” Fairchild said. “But you can choose to control the social and political and economic chaos. You’re going to have more chaos, more devastation when you have people dropping dead in the streets because government’s not doing anything.”

A return to campus

About 1,500 Ohioans died after contracting the flu, according to the Ohio History Connection’s website. Ohio was largely saved from the devastation of the flu by being located closer to the center of the country. The cities and states hardest hit by the disease were on the coasts.

Students returned to campus Nov. 12, 1918, one day after an armistice ended World War I on the eleventh day of the eleventh month at the eleventh hour. According to the annual report, few cases of the flu were reported in the 1919 spring semester.

That year’s Makio — the student yearbook — recorded the names of the dead alongside those who died during the war. At least 17 alumni and three spouses of three faculty members died from the flu and 41 alumni and students died because of their direct involvement in World War I, many of whom died from the flu.

“None of the war classes have lived through as many changes as the Class of Nineteen,” the Makio reads. “Strange were the days, our Alma Mater: when you were dark for the coal sent to the ships, or for the epidemic of the flu, when day by day the fellows we knew were saying gay goodbyes, when our girls were marrying from the very classroom, or returning changed and mute, what time another blue star changed to gold: strange days and great, Alma Mater, our Mother of Honor! Now stand up everybody, for the greater days of peace and the more beautiful Ohio that shall be: all together once more, the yell Ohio!”