Nine hundred and one days after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, U.S. General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, message in hand.

A stand-alone photo in the June 20, 1994 edition of The Lantern of a boy and his grandmother at a Juneteenth celebration in Columbus. Credit: Lantern archives

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free,” Granger read. Behind him were U.S. troops to enforce the words written into law nearly two-and-a-half years earlier.

June 19, 1865 marked the difference between abolition in theory and in reality. Despite Lincoln’s 1863 executive order and Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender in April 1865, news of the end of slavery did not reach slaves in Texas until Granger’s announcement. Hasan Kwame Jeffries, an associate professor in the Department of History at Ohio State who specializes in African American history, said Texas’ location on the western frontier of the Confederacy meant it was away from most of the Civil War battles — and the Union.

“It was a place where enslavers retreated, moving from South Carolina and Georgia and going to Texas with their enslaved folk in order to keep their interest in their ‘property,’” Jeffries said. “Texas was a little bit of an outpost.”

Now, 155 years later, Juneteenth comes amid weeks of nationwide demonstrations following the deaths of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and other Black Americans who have died due to police and racial violence. It is in this context that Jeffries said that the Texas holiday started in 1866 has an opportunity to demand national attention.

“It’s an affirmation of Black humanity and Black dignity, and at the same time, it’s a recognition of the way in which African Americans have struggled for a literal emancipation, a struggle to gain a literal freedom, but then also a struggle to gain those basic rights of freedom,” Jeffries said.

Jeffries said although cities in Ohio have celebrated the holiday, he has never heard of an official Juneteenth celebration at the university. He said one reason could be that the holiday occurs in the summer, when students are away from campus.

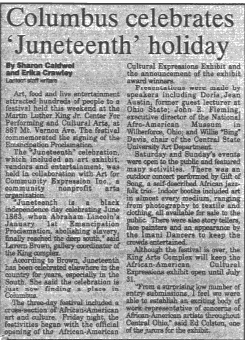

An article from June 21, 1993 in which a source says Juneteenth celebrates June 19, 1863 instead of 1865. It is the only article in the archives that covered a Juneteenth celebration. Credit: Lantern archives

But another reason, he said, could be the university’s demographics. Of the university’s 58,491 students on the Columbus campus, 3,744 students — 6.4 percent — were Black, according to the spring 2020 15th-day enrollment report.

“You gotta have Black people at Ohio State in order to have a celebration,” Jeffries said.

In the Lantern archives, which date back to January 1881, there are three mentions of “Juneteenth.” The earliest is a June 21, 1993 article about a celebration of the holiday in Columbus, in which Lavern Brown, then the gallery coordinator for the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Performing and Cultural Arts, incorrectly called the holiday a “black independence day celebrating June 1863” instead of June 1865.

The second reference to Juneteenth is a stand-alone photo of a boy with his grandmother at a Juneteenth event in Columbus in the June 20, 1994 edition of the newspaper. The last reference is in an article from June 24, 2003 about children dying due to gun violence in Columbus, two of whom were shot during Juneteenth celebrations that year.

The day more commonly celebrated as a holiday, Jeffries said, is Emancipation Day on Jan. 1 — the day Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. In fact, he said the village of Gallipolis, Ohio, has been celebrating the holiday since 1863, making it one of the oldest continuous Emancipation Day celebrations in the nation.

There are 41 mentions of “Emancipation Proclamation” in the Lantern archives in commemorative articles, letters to the editor, commencement speeches and literary reviews.

An article from the Feb. 12, 1987 edition of The Lantern about an Ohio State professor’s commemoration of Emancipation Day. Credit: Lantern archives

Jeffries said a major reason why Emancipation Day is more recognized than Juneteenth is that Emancipation Day signaled to the country — and the world — the end of slavery, while Juneteenth was of significance primarily to Texas. He said Juneteenth’s popularity ebbs and flows with national attention toward Black Americans; it began to spread, for example, with the Black Power movement during the late ’60s and early ’70s and has since found itself reaching Black communities across the country through social media.

But another reason Jeffries said Emancipation Day prevails over Juneteenth is the difference in what each day actually commemorates. He said in history, it is usually white voices that are centered and amplified.

“[Juneteenth] has to do with the people who were liberated,” Jeffries said. “The Emancipation Proclamation has to do with the person who signed the document.”

The Office of Diversity and Inclusion is hosting a virtual Juneteenth celebration Friday with the National Museum of African American History and Culture, with links to pre-recorded presentations, music performances, recipes and activities on its website.