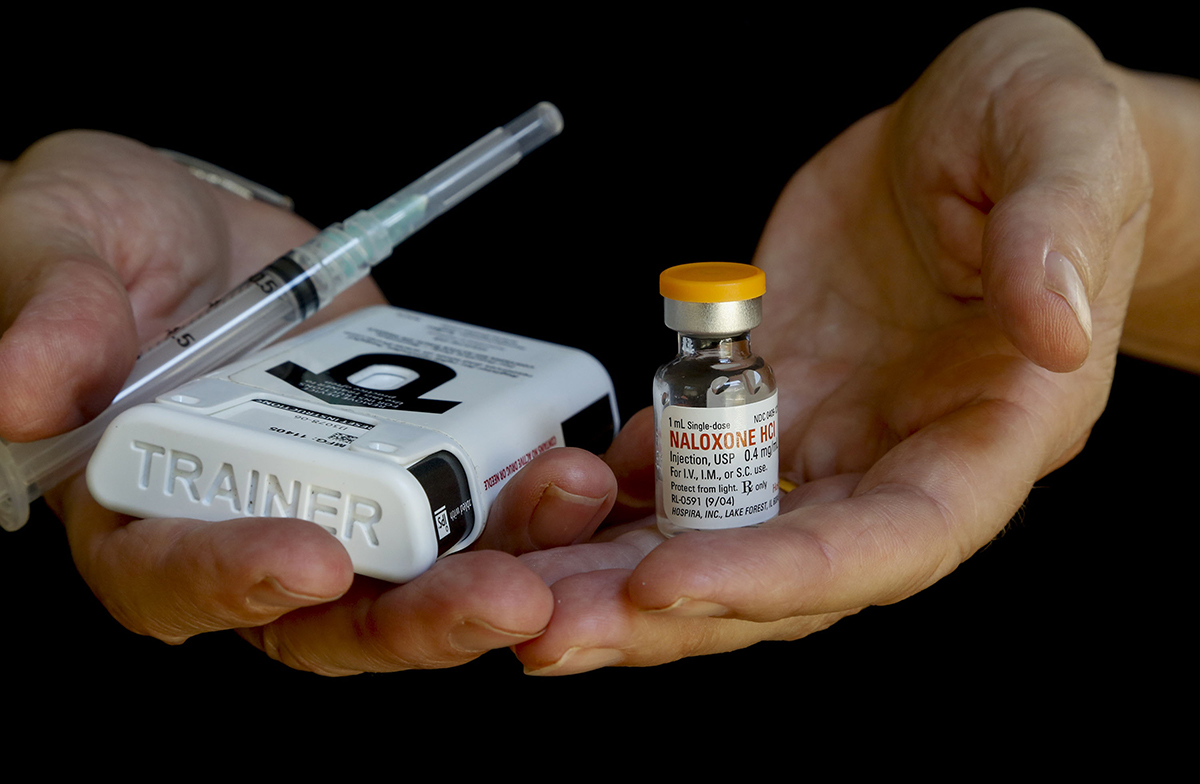

A vial of naloxone — known by the brand name Narcan — and an injector kit of the drug that is used as an antidote to overdoses. Credit: Courtesy of TNS

A group of nine Ohio State students is working to create an app to save lives from the opioid epidemic by identifying and notifying users of drug batches that have been contaminated with highly lethal chemicals in the Columbus area.

The Supporting Ohioans throughout Addiction and Recovery Initiative has partnered with Columbus Public Health and the Columbus and Franklin County Addiction Plan to create and launch the Deadly Batch app, as well as other life-saving measures, according to a press release from the SOAR Initiative. The anonymous alert function is already available, and the rest of the app is planned to be finished by the end of September, Pranav Padmanabhan, a third-year in public health and geography and executive director of the SOAR Institute, said.

“Students are not immune from the effects of the opioid epidemic and the overdose crisis in Columbus,” Dennis Pales, a third-year in biology and public affairs and the director of community relations for the SOAR Initiative, said. “And we want more students to sign up for this alert system, especially as the risk of potent batches of drugs is increasing in Columbus.”

In 2019, 547 people died by drug overdose in Franklin County, and the county is on track to surpass that in 2020, with 168 having died in the year’s first quarter, according to the Columbus Department of Public Health website. This is up from 115 in the first quarter of 2019.

In 2020, there have been 3,235 emergency medical services runs and 2,952 suspected emergency room visits for overdoses in Franklin County and Columbus, according to the Columbus Department of Public Health website. Eighty-six of the EMS runs and 59 of the emergency room visits have come from the 43201 zip code, where many students live off campus.

The Deadly Batch app serves as an opportunity to unite technology and community to inform people about the drugs they are using, Padmanabhan said.

People are able to submit feedback on the app to create an anonymous communication stream among drug users, their loved ones and public health officials in a way that was not possible before due to “structural barriers,” Padmanabhan said.

Typically, people are hesitant to report overdoses due to fear of criminal consequences, Anne Trinh, senior program manager for the Addiction Innovation Fund at the Ohio State College of Public Health, said in an email. She said the legacy of the war on drugs — a government initiative started in the 1970s to decrease drug use by imposing harsher sanctions on drug users and dealers — the stigmatization of people with addiction and the overprescription of opioids in the 1990s has created a culture of mistrust of the criminal justice system among drug users.

Thousands of non-violent people are in jail for drug use, Dennis Cauchon, president of Harm Reduction Ohio, an organization that works to reduce the harms that come with drug policy such as overdose deaths, mass incarcerations and stigmatization, said.

According to a 2018 study conducted by the Kirwan Institute at Ohio State, approximately 2,600 Ohioans are in prison with drug possession as their most serious offense. There were nearly 50,000 Ohioans in prison at the time of the study, which has them at more than 130 percent of capacity.

“We imagine that it’s okay to treat people who use unapproved drugs this way, but it’s not,” Cauchon said. “That’s what the drug war is, it’s a civil war against unpopular people using unpopular substances.”

Cauchon said the war on drugs is also a cause of overdose deaths.

“It’s the inevitable result of not allowing open and regulated markets,” Couchan said. “It’s the same thing that happened with alcohol prohibition. When you make a substance illegal, then [drug users are] going to get hurt and killed.”

Trinh said Ohio is working to change the laws and destigmatize drug usage and addiction and that the Deadly Batch app will play a large role in that. The app uses the science of addiction to lay the groundwork for a shift in public health policy.

The American Medicine of Addiction Medicine defines addiction as a treatable, chronic medical disease that involves complex interactions between the brain, genetics and an individual’s environment and life experiences, and people who suffer from addiction use substances and engage in behaviors that become compulsive and persist despite their negative consequences.

“It’s not a moral failing, it’s not a choice. It affects your brain so it makes it harder for you to make decisions the way people who don’t use drugs make decisions,” Trinh said.

Trinh said apps like the Deadly Batch app are a part of a cultural shift in the science of public health.

“Giving affected populations more voice and representation is a way to ensure that our institutions don’t make any assumptions about what’s right or helpful when it comes to alleviating the impacts of the opioid and drug overdose crisis in Ohio,” Trinh said.

The app also provides access to harm reduction and treatment resources, Padmanabhan said.

Harm reduction resources include organizations such as Harm Reduction Ohio, which offers a statewide online ordering of naloxone — also known by the brand name Narcan — a life-saving overdose reversal nasal spray that wipes out opioid receptors in the event of an overdose, and local syringe programs, such as Safe Point, that allow users to obtain sterile needles to avoid infectious disease, Cauchon said.

Padmanabhan said the partnership with Columbus Public Health, worth $48,000, is beneficial to all parties combating the opioid epidemic.

“Since we’re a third party, we’re a nonprofit, we can build more trust in the community, and we have avenues that we can build relationships with them that don’t involve some sort of administrative or police presence, which is a big concern among the population that we’re trying to reach,” Padmanabhan said.

Padmanabhan and Pales are both members of Buckeyes for Harm Reduction, a student organization that aims to provide support for those impacted by the opioid epidemic and advocate for harm reduction, according to the organization’s mission statement.

Padmanabhan said he had the opportunity to volunteer at Columbus’ needle exchange and became passionate on the issue after seeing its effect on the community. Pales shared a similar path, but he said some of his motivation stems from watching close family members struggle with other addictions.

“It’s easy to feel helpless, like there’s not a lot you can do about it,” Pales said. “You know the disease is so innate that there’s no treatment, there’s no cure, there’s just something that makes you feel powerless.”

But Pales said that is not the case.

Overdoses are preventable through things such as fentanyl test strips and naloxone, Pales said.

Fentanyl is a strong opioid used to treat severe pain, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Padmanabhan said common recreational drugs used frequently by college-aged people, such as cocaine, can be laced with it.

Cauchon said that it is a myth that marijuana can be laced with fentanyl.

Students can receive Narcan for free on campus, at the pharmacies at Doan Hall and the Ohio State East and James Cancer Hospitals, according to the Wexner Medical Center website. Narcan is also available for free through the mail from the Franklin County Department of Public Health and the Columbus Department of Public Health.

Fentanyl test strips are currently available from Columbus Public Health and local smoke shop Waterbeds ’n’ Stuff. In February, the Undergraduate Student Government passed a resolution that recommended the university provide fentanyl test strips in the Student Wellness Center with instructions on how to use them and advertisements on how to access them.

Although the app is not yet available, people can send and receive anonymous alerts about batches of drugs by texting “SOAR” to 614-768-7627.