Following Ohio State’s mandated lockdown in March of last year, the Meat Lab located in the Animal Science Building, kept their doors open, but saw changes in the lab and had to conform to the new guidelines. Credit: Mackenzie Shanklin | Photo Editor

When Ohio State’s campus shut down last March, the meat lab — the university’s slaughter facility which provides meat for public sale — adapted to sudden changes in the lab, saw a shift in workload and battled to keep workers around to help.

Whirlwind timeline

After the start of the COVID-19 pandemic at Ohio State, meat lab employees were originally told it’d be “business as usual,” Ronald Cramer, meat lab manager, said.

To stay open, the lab had to prepare for an expected surge in demand, Cramer said. Workers prepared extra cuts and filled more freezers. The lab operated for several weeks after the university shut down. Then the inevitable happened.

“We were [told] on a Wednesday that we had to be shut down by Friday,” Ethan Scheffler, assistant technician at the meat lab, said. “You can’t just close the doors on a meat market.”

Cramer said the lab’s closing put several students out of a job.

“All those kids, of course, they don’t have a job and the means for the extra cash, so they all went home,” Cramer said.

With freezers stocked to the ceiling with fresh product, managers had to request an extension to stay open so managers could monitor freezers a few times a week, Cramer said.

Only a few months later in May, the meat lab was allowed to reopen — but with limited staff. Only three student employees were around to help during the summer, Scheffler said.

Changes in the lab

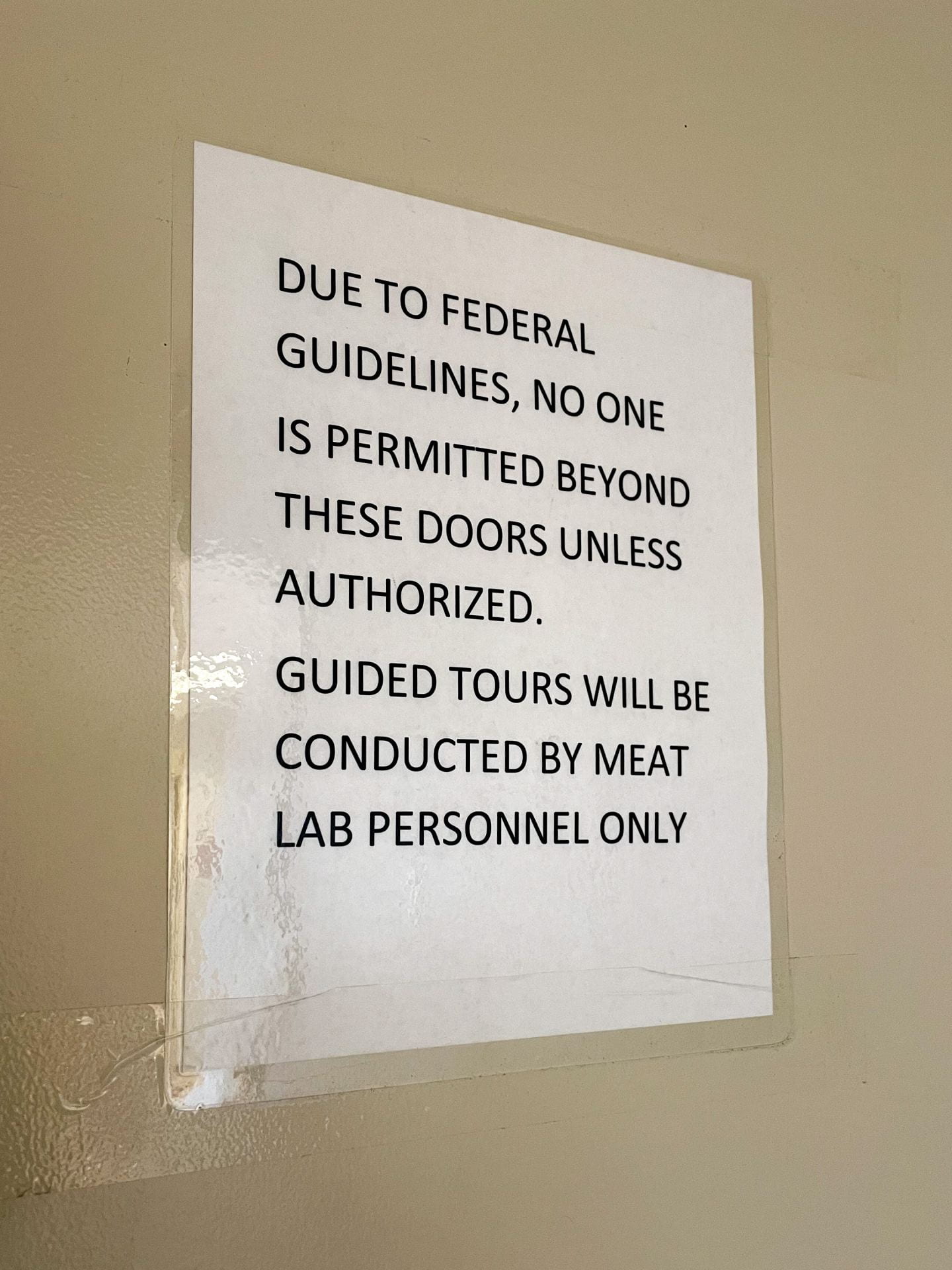

Scheffler said the lab implemented social distancing, mask wearing and no-contact customer pickup in order to follow COVID-19 safety guidelines set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“The social distance thing was probably one of the biggest problems for us,” Scheffler said.

Space limitations and the hands-on nature of the job created a constant battle to maintain social distancing. The easiest guideline to follow, Scheffler said, was cleaning protocols — due to strict sanitization requirements set by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for butchering facilities, staff were already used to thoroughly sanitizing every nook and cranny.

Shift in workload

Beyond changes in the lab’s daily operations, Scheffler said there were major fluctuations in business from wholesale, retail and personal sales.

With fewer extension programs, youth agriculture activities, facility tours and classes participating in the lab, fewer animals were needed, Cramer said. With no need to have animals ready for these demonstrations, the lab cut down.

“We’ve dropped our harvest schedule down to a minimum,” Scheffler said.

When Ohio ceased in-person dining at restaurants, the meat lab faced revenue loss, Scheffler said. Depending on the time of year, the meat lab typically provides products for up to five restaurants. Without the business from these restaurants, the lab had to cut back production.

While the lab faced major downsizing in their production for restaurants, extension programs and more, the opportunity arose to increase business through other avenues. In the midst of a meat shortage, the meat lab didn’t fail to provide.

Personal orders flooded in. The nearly 800 pounds of ground beef prepared in anticipation of a shortage was bought out in a matter of weeks, Cramer said. Professors, students and community members rushed to place orders from the lab, forcing the lab to restrict items per order to prevent shortages.

Beyond personal orders, Cramer said the lab saw an increase in orders in the fall for staple items at campus dining locations such as Sloopy’s and Woody’s. One location needed more than three times the amount of beef patties it usually does.

Overall, Scheffler said the meat lab tried to regain a sense of normalcy through doing what it does best.

“We’re not large scale, we’re not small scale, we’re not medium scale. We have to hit everything in between,” Scheffler said. “Teach, do research, and work with the university to make a product.”

Finding and keeping workers

Behind the battle to stay afloat in the rush of orders was a small team of managers and student workers. Where a typical semester would see between eight to 12 student employees, only four returned to work in the fall.

Students usually hear about working for the lab through classes or flyers in the hall, but COVID-19 limited that exposure as fewer people were on campus, Cramer said.

“We don’t have contact with the kids like we used to,” Cramer said. “They just don’t either come on campus or are only here one day a week for a lab.”

The employees who did stick around saw increased hours, yet enough flexibility in their schedules to accommodate this change, Cramer said. With many virtual classes, student employees were able to attend class from the building and start working right after.

With a team of just six, it seemed impossible to function with any less.

However, both student workers and managers were kept away due to exposure to COVID-19. Brittany Wiseman, a fourth-year in meat sciences and a meat lab student employee, said she missed weeks of work on two separate occasions because she had to quarantine.

“They just told me not to worry about it because my job would be there when I came back, so it wasn’t a big deal, which made it really nice especially when you’re in quarantine and you’re freaking out,” Wiseman said.

Both Cramer and Scheffler said it’s important their employees’ mental and physical needs are met before any work is done.

Scheffler said through occasional taste testing, Buckeye Donut Friday’s and a lot of joking, the meat lab team makes work enjoyable for everyone. Although the task of butchering and processing animals may seem like a nightmare to some, it serves as a relaxing hobby for others.

“It’s a lot of fun. My bosses are ornery,” said Wiseman. “If anybody’s willing to do what I do, it’s a good time.”