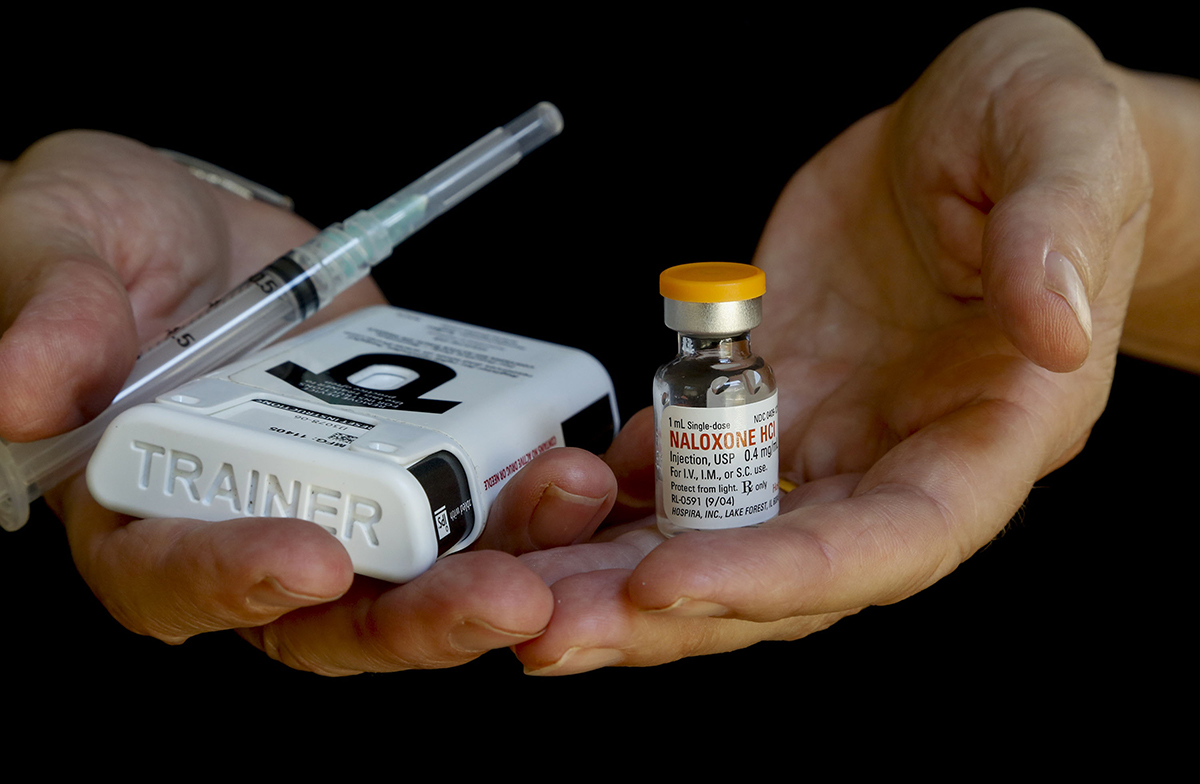

A vial of naloxone — known by the brand name Narcan — and an injector kit of the drug that is used as an antidote to overdoses. Credit: Mark Boster/Los Angeles Times via TNS

Ohioans who live in areas with low access to treatment for opioid-related overdoses are less likely to maintain sobriety, an Ohio State research study suggests.

Researchers at the Wexner Medical Center at Ohio State and the Colleges of Public Health, Social Work, and Arts and Sciences found the likelihood of a person staying in treatment for opioid use drops by as much as 50 percent when a provider is more than a mile away, according to the study published May 12.

An area or neighborhood is considered an opioid treatment desert when there is low access to treatment for opioid-related overdoses, presenting a barrier to those who seek treatment, Ayaz Hyder, lead author of the study and assistant professor in the College of Public Health, said.

“The main finding was that opioid treatment deserts exist across the county, across the city of Columbus,” Hyder said. “They’re not necessarily focused in any one specific area, and that makes sense when we think about how this epidemic has evolved.”

Researchers mapped treatment deserts using emergency medical services data from 2013 through 2017, Gretchen Hammond, co-author of the study and community lecturer in the College of Social Work, said.

They tracked 6,629 EMS runs in which paramedics administered the overdose drug naloxone to adult patients. They then compared the locations of these runs to the distance and time it took to travel to the nearest treatment provider who offered medication-assisted treatment services, according to the study.

The study found the median travel time by car was two minutes, compared to 17 minutes by public transportation, Hammond said.

“What we’ve created is a way to sit and say, ‘Why don’t you look at data on a map?’” Hammond said. “And based upon this calculation of a treatment desert, you could make a better decision where to put maybe your next treatment center, or your next location, or your next access point.”

Hyder said COVID-19 exacerbated the opioid epidemic. The study viewed its effect on Black and white people across different demographics and socio-economic backgrounds.

Black individuals who had an opioid-related overdose tended to live close to treatment providers that offered medicated-assisted treatment, while white individuals lived farther, Hyder said. However, he also said Black individuals who seek treatment face discrimination, stigma and racism — barriers to treatment that white individuals don’t face.

“Even though white individuals may live farther away, they may actually have a different set of resources that allow them the capacity to seek treatment,” Hyder said

Hyder said the Columbus & Franklin County Addiction Action Plan can use these findings to identify and fill the gaps in access to treatment.

In 2019, there were 4,028 unintentional drug overdose deaths in Ohio, according to the Ohio Department of Health. The drug fentanyl –– an opioid –– was involved in 76 percent of overdose deaths, often in combination with other drugs.

Of the overdose deaths in 2019, 29.4 percent of individuals who died were Black, while 66.2 percent were white.

In Franklin county, there were 798 total deaths due to overdose in 2020.

Hammond said the research team has already advised treatment providers on opioid treatment deserts within Franklin county. The team is partnering with health care, public health and community organizations to translate overdose data into actionable items that will combat the opioid epidemic.

“I’d love to see this expand to other counties, because again, the ability to make a decision where you have not just one type of data in front of you, but lots of data sets that help you get a more comprehensive picture of what might be going on, ultimately will result in you making a more informed decision,” Hammond said.

![Ohioans might have to pay to access police video footage after Gov. Mike DeWine signed House Bill 315 into law Jan. 3. Credit: Andrew J. Tobias via TNS [Ohio flags fly at the Statehouse in Columbus. Not every citizen constitutional amendment in Ohio turns out as planned. The 1992 term-limits amendment is a good example, writes Bob Paulson in his column today. Credit: Andrew J. Tobias via TNS]](https://www.thelantern.com/files/2025/01/20241219-AMX-US-NEWS-LAWMAKERS-PASS-SEXTORTION-CRACKDOWN-PROPOSE-1-PLD-384x253.jpg)