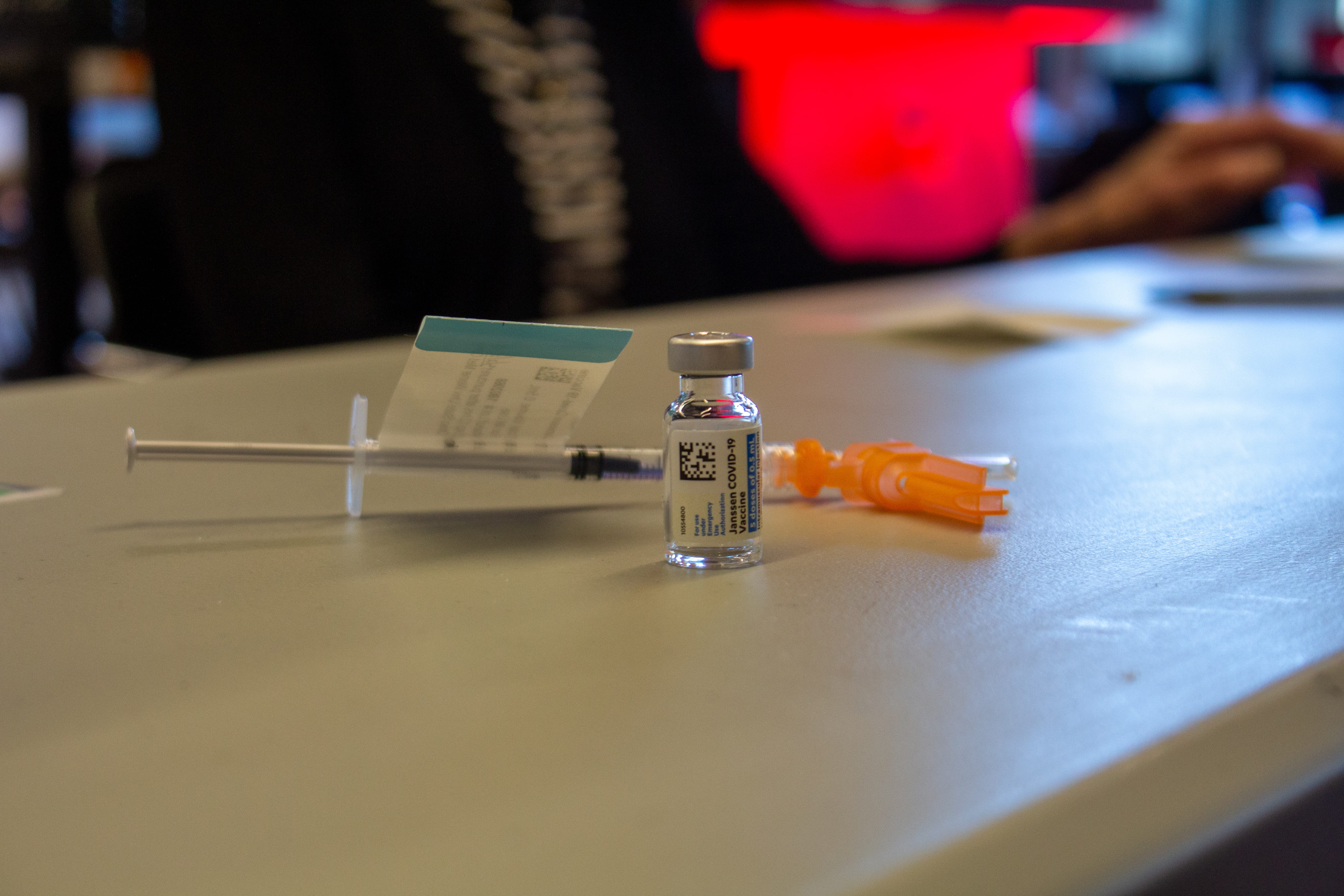

A new study from Ohio State researchers found that the gap in vaccination rates between Black and white Americans may be due to unequal access rather than vaccine hesitancy. Credit: Owen Milnes | Lantern File Photo

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy has declined significantly among Black Americans since vaccines became publicly available in late 2020, according to a Jan. 21 study by Ohio State researchers.

Researchers charted the COVID-19 vaccine willingness of 1,200 American adults over a six-month period and found that vaccine hesitancy among Black participants dropped from 38 percent in December 2020 to 26 percent by June 2021, according to the study.

Conversely, vaccine hesitancy among white Americans remained stable over the same period, starting at 28 percent and ending at 27 percent, according to the study.

Tasleem Padamsee, assistant professor of health services management and policy and lead author of the study, said participants reconsidered their vaccination status due to a new understanding that the vaccine would help protect members of their community.

“Anybody who believes that the vaccine is going to protect themself or their community is more likely to get vaccinated, and that doesn’t differ by race. What does differ is whether people believe that or not,” Padamsee said. “Black participants over this time period came to believe more strongly that vaccines were necessary to protect themselves and their communities.”

The paper stated that Black Americans’ initial vaccine hesitancy stemmed from the medical community’s history of unethical and abusive treatment of Black patients.

Documented instances of institutional racism in medical research and development, such as in the case of the Tuskegee syphilis study and the nonconsensual use of cancer cells from Henrietta Lacks, have led to broad distrust of the health care system within the Black community.

Despite a shift in willingness to get the vaccine, vaccination rates of Black Americans have continued to lag behind those of white Americans. Fifty-four percent of Black Americans have received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose, compared with 60 percent of white Americans, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Kelly Garrett, interim director of the School of Communication and co-author of the paper, said insufficient access to vaccines may be the more significant factor in this disparity.

In addition to physical barriers such as fewer vaccination sites in predominantly Black areas, Padamsee said the intersection of race and class could explain why Black Americans are encountering greater difficulty accessing the vaccine than white Americans.

“We know that African Americans are more highly concentrated in the kinds of jobs where they have a hard time taking a day off because they will lose pay,” Padamsee said. “Service industries, retail industries, manual labor industries, where one day’s work really does equate to one day’s pay. So if you don’t show up on a particular day, you don’t get paid for that particular day.”

Garrett said access is not just about messaging, but about an on-the-ground effort to break down these physical and historical barriers.

Padamsee said this on-the-ground effort is ultimately contingent on health care workers being given the necessary resources to identify and address specific barriers to care in their individual communities.

“We need to put a lot of energy and time and money into allowing the agencies and organizations who know how to do this to go into these communities, talk to people and find the access barriers,” Padamsee said.