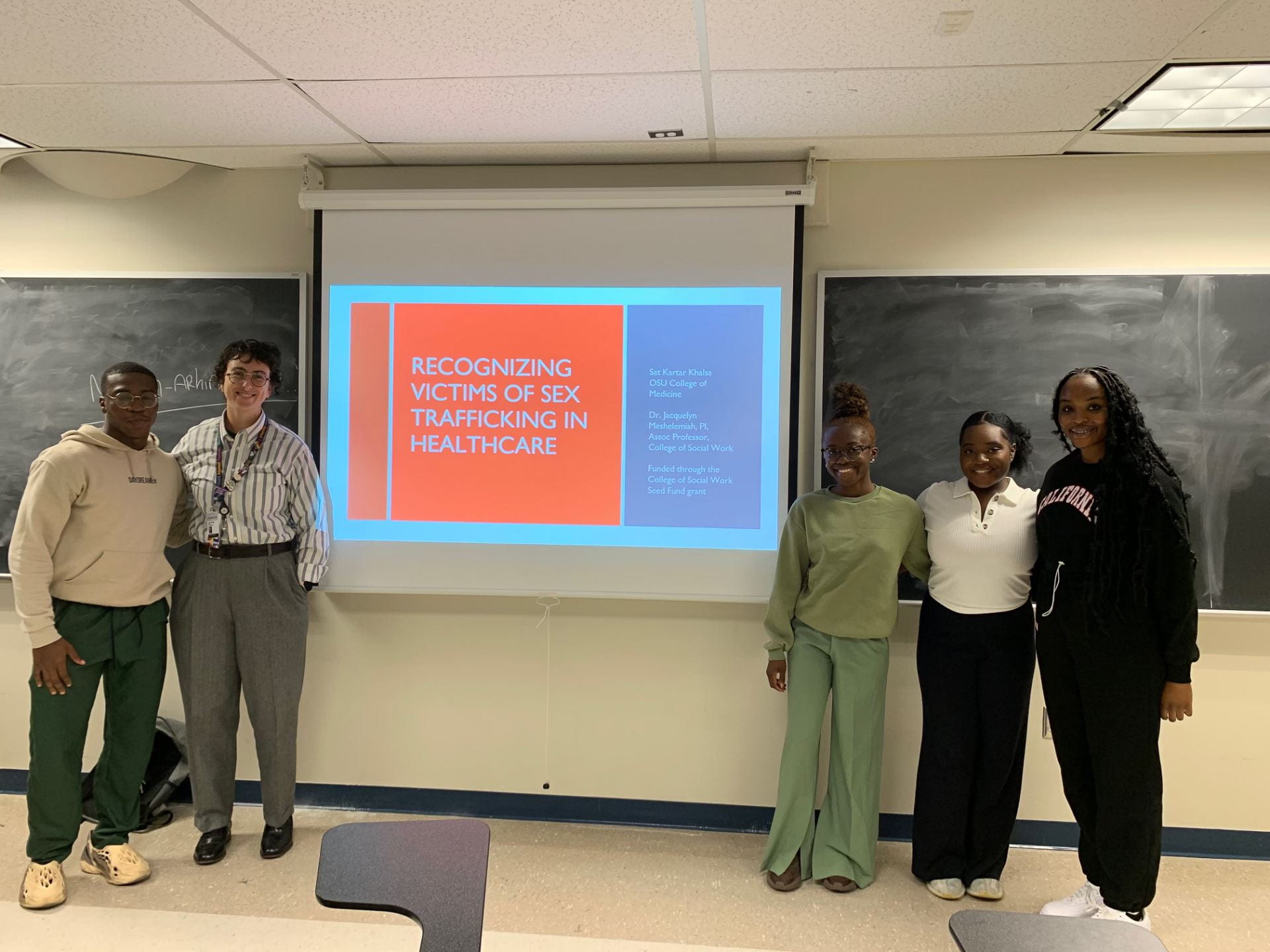

With the goal of raising awareness to sex trafficking for medical students, In Safe Hands is a student organization that addresses stigmas and myths about sex trafficking victims for future medical students. Credit: Amani Bayo | Lantern Reporter

Medical students must prepare to care for all kinds of patients, but Isaiah Boateng, founder of the student organization In Safe Hands, noticed a gap in the curriculum.

Boateng, a third-year in biomedical science, said he created the organization to help future medical students understand the stigmas surrounding victims of human trafficking and how to care for them in medical settings.

According to UNICEF, many cultures look down upon participation in the sex industry, whether it is forced or not. In the U.S. most states “treat child sex trafficking victims as criminals,” according to its website, and survivors of sex trafficking may experience shame and isolation.

As a future medical student, Boateng said he wondered how stigmas could creep into health care.

“Human trafficking can happen to anybody — doesn’t matter what you look like — so it’s important to know what human trafficking is, more than what we see on TV and what we hear in the news,” Boateng said.

The National Human Trafficking Hotline — which records reports of human trafficking — collected 51,667 “substantive” phone calls, texts, emails, online tips or webchat reports of trafficking nationwide in 2020, according to its most recent report. For Ohio, the hotline recorded 1,087 reports in 2020.

Boateng said health care providers are often unaware of how to identify and offer the best help for victims of human trafficking, but providers are in a position to provide medical care and access to support.

Boateng said educating prospective medical students on how to identify victims by characteristics, such as physical injuries, can aid in overall prevention.

“You can’t see what you don’t know,” Boateng said. “Changing minds is very much the first start.”

Boateng said the organization meets biweekly to connect with current medical students who can share their experiences in hospitals and discuss ways to improve victim identification.

“I think first and foremost to educate students who are health-oriented and hope to move into a health care-related field or career in the future,” Boateng said. “I think, if we just increase their knowledge, they’re gonna have a higher likelihood of recognizing human trafficking.”

Sat Kartar Khalsa, a fourth-year medical student who uses they/them pronouns, shared their experiences at an Oct. 6 In Safe Hands meeting to address stigmas and myths about human trafficking victims in health care.

Khalsa said they spoke to 50 female victims of sex trafficking from Columbus to see how they were treated in clinical spaces and to determine how health care providers may indirectly contribute to the stigma surrounding sex trafficking.

“There’s not a ton of research about their experiences in the health care system,” Khalsa said. “I figured that they were bad, but I didn’t know how bad.”

Khalsa said victims often seek medical attention in the emergency department for injuries often related to drug use, which causes doctors to dismiss them as addicts.

“It’s not required that you get trained to identify, screen and treat sex trafficking victims, and so a lot of them just don’t know,” Khalsa said. “I want to provide the information so that folks who do care have the resources to do something with that information.”

Khalsa said the best aid doctors provide for victims who enter the emergency department is to supply them with sufficient, judgment-free care and be as upfront as possible about their choices.

“A lot of victims don’t actually know that they’re trafficked because they think they’re doing all this of their own will,” Khalsa said. “The main thing you want to do is provide these women agency over their bodies and their lives.”

Khalsa said by starting to address sex trafficking and changing the moral perspective, there is a potential to destigmatize other social issues that are also barriers in health care.

“Everything about sex trafficking is also destigmatizing so many other things,” Khalsa said. “It’s bringing attention to racism or biases, to sexism and the patriarchy, to sticking around mental health, substance use, everything.”

Naa Dromo Korley, a third-year in medical anthropology and community outreach chair for In Safe Hands, said the organization plans to play a more active role in victim recovery by partnering with The Freeman House — a Columbus house for human trafficking survivors to live independently in sobriety.

“It’s one thing to hear about it, but it’s also another thing to go out and actually see what’s going on,” Korley said. “Being hands-on and being able to help survivors, I think it’s very powerful.”

In Safe Hands is run completely by Black students, and Korley said the organization also acknowledges the racial disparities in human trafficking that often go unnoticed and block out victims from marginalized communities.

“Black people in general don’t get a lot of spotlight in things, so just being able to stand on the gap here at a predominately white institution is just a very strong statement,” Korely said.

Boateng said by discussing the realities of victims in clinical spaces, students can establish better equipped spaces in aid and prevention.

“If we start with the students on campus moving to the direction of health care, if they’re a little bit more knowledgeable about the realities of human trafficking, they’re a little bit more inclined or prepared to step in,” Boateng said.