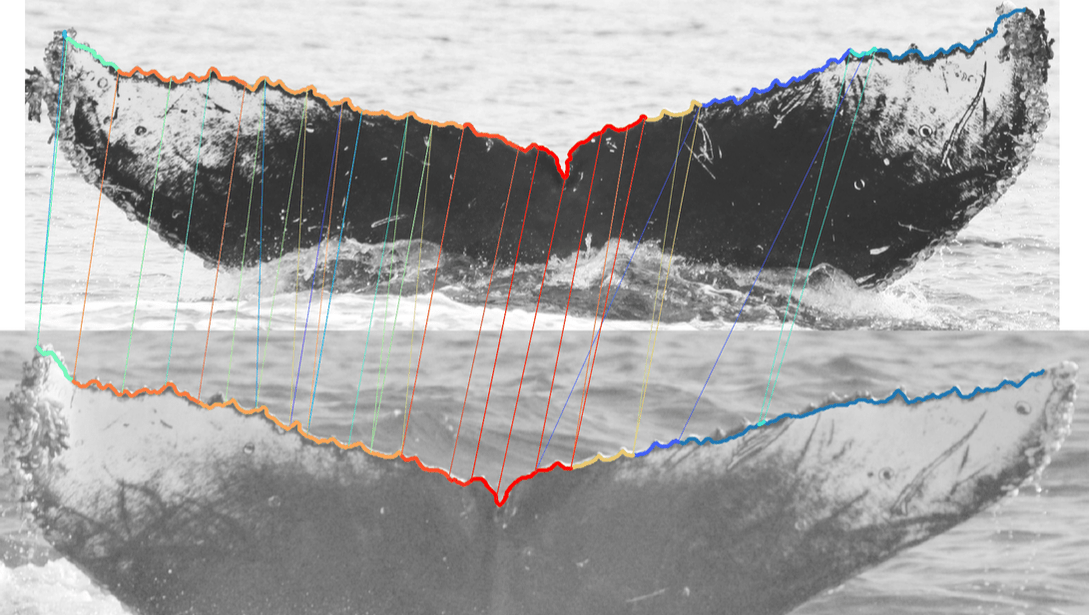

Software framework WildBook utilizes AI and machine learning to differentiate individual animals based on unique characteristics, such as the curvature of a whale’s fluke. Credit: Courtesy of WildMe

What began as a friendly wager between colleagues, mixed with engineers’ competitive nature, has since established one of the premier technological advancements in the environmental conservation space.

In the late 2000s, now Ohio State professor Tanya Berger-Wolf found herself wondering how biologists differentiated one zebra from another, a crucial step in estimating a species’ population and identifying population trends. It was then that Berger-Wolf encountered the popular mark-recapture method, which involves corralling, tagging and releasing an animal, then returning to that location at a later time to count each marked animal.

When she encountered this lengthy and tedious process, Berger-Wolf found herself thinking of ways to make it more efficient.

“My colleagues were like, ‘Tanya, you’re so impatient. Do you think you can do it better?’ and I was like, ‘You want to bet?’” Berger-Wolf said.

In 2010, Berger-Wolf — then a professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago — and a Ph.D. student developed a method of identifying individual zebras with just two clicks of a mouse using machine learning and photographs, Berger-Wolf said.

The program identified zebras by analyzing the animals’ stripes, which are distinct to each animal, just as a fingerprint is for humans, Berger-Wolf said. She said the program assesses user-submitted photos of zebras to determine whether the photographed animal’s stripe pattern already exists in the database; if not, a new identification is given to that zebra and it is added to the database.

Over the next few years, with the collaboration of biologist Dan Rubenstein and computer vision researcher Chuck Stewart, the software program was further developed to enhance accuracy and include additional species, Berger-Wolf said.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the country in Portland, Oregon, conservationist Jason Holmberg was developing a similar program that could be used to identify individual whale sharks, Berger-Wolf said.

Also an avid scuba diver, Holmberg had been aware of the widely used mark-recapture method of identifying animals. Because of the method’s time-intensive nature, Holmberg wondered if animals could be more efficiently tracked by digitally “tagging” them via photograph.

Little did either scientist know, Holmberg’s theory was practically the same one Berger-Wolf was expanding upon, Holmberg said in an informational video.

“The problem with mark-recapture is that it’s really difficult to do and takes a lot of time, years and years of research, in fact, and it often involves hurting an animal with a tag,” Holmberg said. “Yet, it’s essential that scientists measure animal populations because thousands of animal species are in rapid decline.”

With identical goals and similar concepts, Berger-Wolf said she and Holmberg were able to combine the best features of their teams’ projects and establish the current versions of the nonprofit Wild Me and software framework WildBook. The framework uses algorithms to identify individual animals through photographs based on various unique characteristics, such as the curvature of a whale’s fluke or the spots of a leopard, Berger-Wolf said.

The Wildbook database is open-source, meaning anyone with a camera can contribute to the data by providing photos of the animals. The database now consists of more than 6 million photos of over 70 different species, ranging from creatures as small as Hawaiian snails to those as large as orca whales, Berger-Wolf said.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature — also known as the IUCN, and is in charge of categorizing threatened species — has over 20,000 species described as “data deficient,” meaning there is not enough data to identify population size and trends to be able to correctly categorize them, Berger-Wolf said.

If a species isn’t officially categorized by the IUCN as threatened, vulnerable or endangered in some way, Berger-Wolf said those animals won’t receive the regulations and protections they may need. This, she said, is where Wildbook comes in.

“The species commission in 2016 met and reassessed the status of whale sharks, and thanks to data from Wildbook, it changed from ‘vulnerable’ to ‘endangered’ and the population trend from ‘stable’ to ‘decreasing,’ not because the species is doing worse, but because the data is much better,” Berger-Wolf said.

Thanks to Wildbook, Berger-Wolf said the IUCN should have enough data on killer whale populations to remove them from the “data deficient” list and officially categorize them the next time the commission meets, which the IUCN webpage states is to be announced. This categorization will allow for the animals to receive the protections they need, Berger-Wolf said.

“I’m not a biologist who will go out in the field and be able to do something directly to protect the species, but what we can do as data scientists, we can help in ways that provide a view into these populations,” Berger-Wolf said.

With thousands of species currently in rapid decline and many on the verge of extinction, Holmberg said it is crucial to have sufficient data so these species can receive necessary protections.

In fact, most scientists believe Earth is currently in the midst of the sixth mass extinction event, and biodiversity is being lost at an unprecedented rate and scale, Berger-Wolf said.

“I’m hopeful that we’ll be able to help numerous animal species who are on the brink of being lost, and that they will survive and even thrive and that one day my daughter will swim with that same whale shark I did 20 years ago,” Holmberg said in an informational video.

More information on Wild Me and Wildbook can be found on Wild Me’s website.