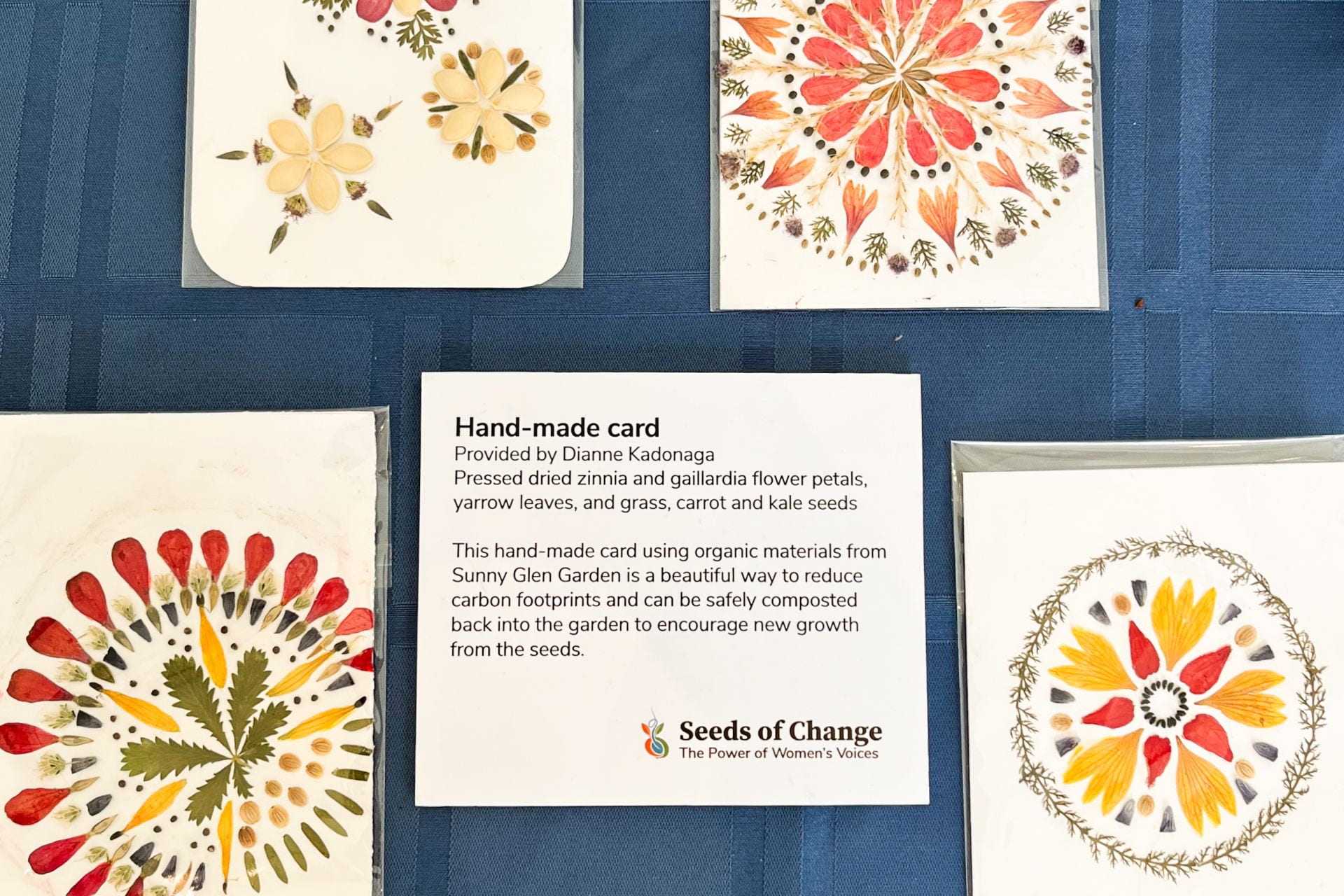

Cards made from pressed flower petals, courtesy of Sunny Glen Garden owner Dianne Kadonaga. Credit: Lauren Spirk | Lantern Reporter

An installation at Ohio State’s own Thompson Library demonstrates how farming takes on a different meaning for BIPOC individuals.

Opened on Jan. 4 and set to close on Sept. 8, “Regenerative Champions” features photographs and written materials that tell the unsung stories of Columbus’ BIPOC — Black, Indigenous and people of color — farmers, according to the University Libraries’ website. As its name suggests, the project also highlights BIPOC farmers who actively engage in regenerative agriculture.

According to the Natural Resources Defense Council’s website, regenerative agriculture is a movement that combats climate change by “farming and ranching in a style that nourishes people and the earth, with specific practices varying from grower to grower and from region to region.” Some common regenerative agriculture practices include limiting soil disturbance and protecting local pollinators, the website states.

Sherifat Alabi, a doctoral student in the Department of Agricultural Communication, Education, and Leadership, is the chief creative behind the “Regenerative Champions” project.

Last year, Alabi asked her adviser Joy Rumble — an associate professor within the department — for guidance in writing the grant proposal that eventually secured funding for “Regenerative Champions.” Alabi said documenting the lived experiences of BIPOC farmers was her driving goal.

Rumble said she became an avid supporter of Alabi’s quest.

“It’s been awesome to really see her passion allow this to be successful and elevate [BIPOC] voices in a way that the farmers and the community can benefit,” Rumble said.

Through her research, Alabi found the No. 1 reason why BIPOC individuals get involved with farming is to tackle food insecurity. By drawing upon their communities’ personal needs, BIPOC farmers have developed a deep understanding of what nutritious agriculture means, Alabi said.

Rumble agreed. She said recognizing the individualized efforts of BIPOC farmers means empowering them to continue growing sustainable and shareable food items.

“We can’t overlook the importance of the work that these small-scale farmers are doing,” Rumble said. “While they may not be feeding the world in a global sense that many of our large-scale farmers are, they are feeding their communities and they’re making change in their communities.”

One of the farmers featured in “Regenerative Champions” is Aaron Hopkins, who founded South Side Family Farms in 2014. Though South Side Family Farms began as a community garden, it has since evolved to encompass two separate farm gardens and a seedling farm, its website states.

Aaron Hopkins, founder of South Side Family Farms, points to a rainwater-catching system at one of his properties. Credit: Lauren Spirk | Lantern Reporter

Beyond his efforts to reduce food insecurity in Columbus, Hopkins is also a minister at the Family Missionary Baptist Church and civic president of the Southside Community Action Network Civic Association.

“I’ve lived in this community for about 35 years,” Hopkins said. “And actually, on this block right here, I raised my family. I’ve got six children.”

When speaking about the challenges he or his neighbors have faced, Hopkins specifically mentioned gentrification and its displacing effects. Due to Columbus’ history of redlining, BIPOC communities have been ousted from receiving proper access to resources, Hopkins said.

In February 2023, a traveling exhibit titled “Undesign the Redline” explored Columbus’ complex history with redlining, or the process of denying loans and investment services to neighborhoods that largely house people of color.

One of redlining’s enduring consequences is a lack of fresh food options within certain areas, Hopkins said.

Through South Side Family Farms’ numerous locations, Hopkins distributes fresh produce to Columbus residents of all ages. He said these residents are encouraged to give back by tending to various gardens, making food deliveries around town and completing modest construction projects.

“Where we’re standing right now, this is considered food apartheid,” Hopkins said. “We’ve got a lot of corner stores that carry beer and wine and lottery and snacks, but no grocery store where we have access to all the fresh fruits, vegetables and meats.”

Another community farmer showcased in the “Regenerative Champions” project is Dianne Kadonaga, whose “Sunny Glen Garden” likewise promotes regenerative agriculture.

Kadonaga said keeping forest gardens — which integrate trees and shrubs into food production, thereby mimicking a woodland habitat — is one way to combat the environmental damage that occurs from having manicured and chemically fertilized lawns.

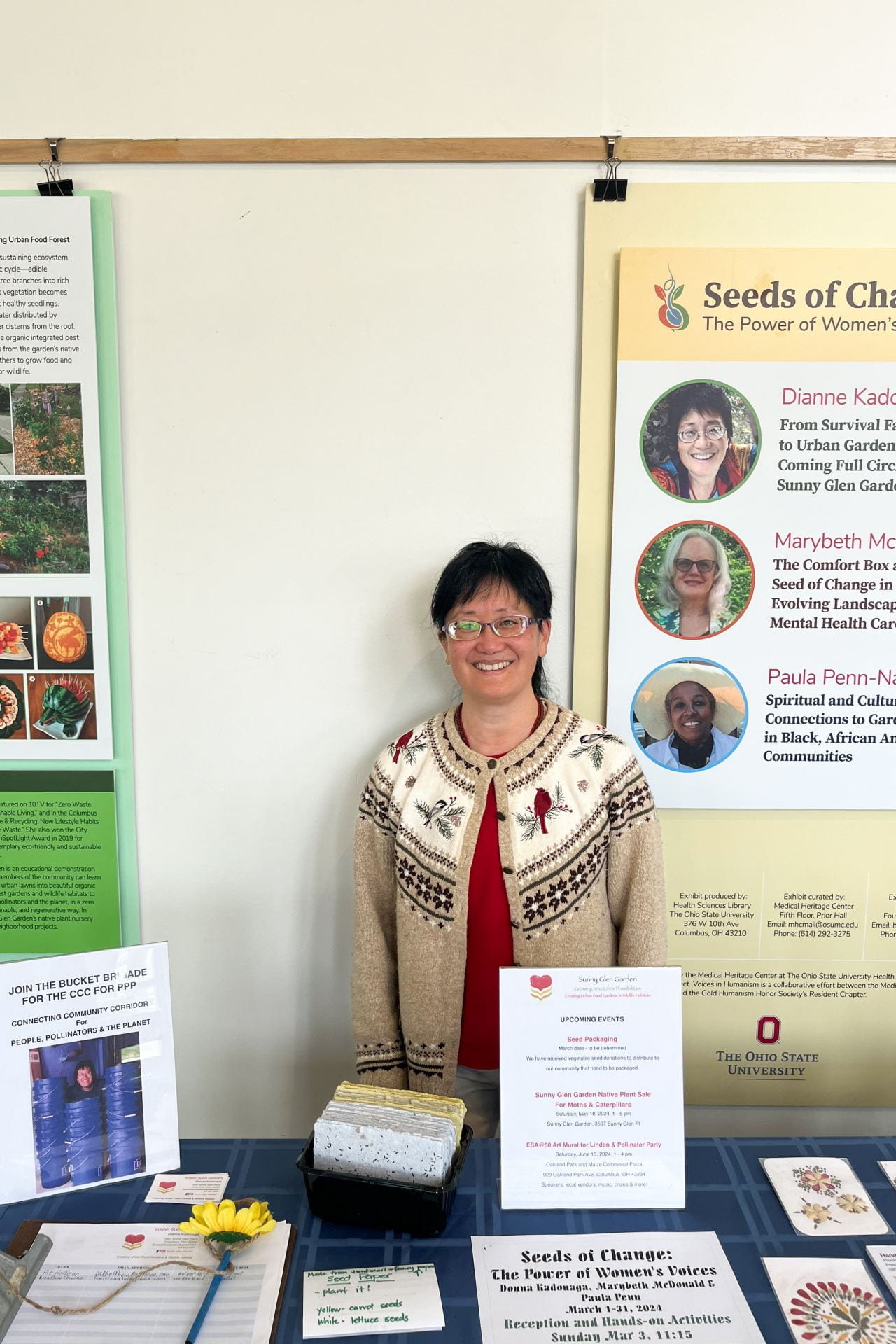

Sunny Glen Garden owner Dianne Kadonaga at a Seeds for Change event on Sunday. Credit: Lauren Spirk | Lantern Reporter

“What I’ve been trying to tell people is to consider having a forest garden instead of an annual vegetable garden,” Kadonaga said. “They usually have more pests, more diseases and usually require more resources because they’re not adapted to our climate.”

Many of the forest gardening strategies Kadonaga employs are drawn from Native and Indigenous cultures. For example, she said a practice called the “Three Sisters Guild” involves planting corn, beans and squash together to encourage the simultaneous growth of all three crops.

“If you’re growing corn, you grow beans and the beans will naturally stalk up your corn,” Kadonaga said. “The beans will provide nitrogen that your corn and your squash will need, and then the squash will provide shade cover that prevents any weeds from coming out.”

One of the major challenges that Kadonaga faces is being a bridge for the gap between BIPOC farmers and other farmers, she said.

Kadonaga recalled a time when she had attended an herb class with friends, during which they sat together as the only BIPOC in the room. Class participants were asked to split up and sit with other people, but when Kadonaga sat next to her new classmate, she could feel a sense of discomfort. Unfortunately, they never made an effort to mingle with her, she said.

“I’m always having to be the one to initiate the conversations,” Kadonaga said.

This type of interaction is only a small microcosm of the cultural barriers within agricultural environments at large, Kadonaga said. While such instances can be frustrating, she said they drive her to continue farming in a socially inclusive manner.

“We can create these edible forests that provide food security, increase the biodiversity, make us more resilient to climate change and help us build community,” Kadonaga said.

More information about Hopkins, Kadonaga and additional BIPOC farmers is available via the “Regenerative Champions” installation in the Thompson Library. The installation’s display hours are 9 a.m. to 9 p.m.