This is part one of a two-part series on mental health and college students. Part two, which focuses on resources available to Ohio State students struggling with thoughts of suicide, can be read here.

When Kayla Higginbotham walked by the Buckeye Campaign Against Suicide table at the involvement fair her freshman year, she had no idea that four years later, she would be helping her peers cope with the issues of mental health and suicide.

“I saw ‘suicide’ written really big, and I know my initial reaction was to be like, ‘Eh? I don’t know about this,’” said Higginbotham, a fourth-year in psychology and women’s studies and the president of Buckeye Campaign Against Suicide. “I definitely think there’s a huge stigma attached to suicide and talking about that, especially on a college campus.”

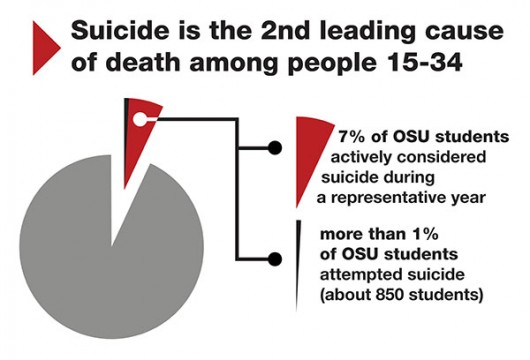

Despite the tendency of young adults to shy away from conversations regarding these issues, suicide is the second leading cause of death for persons aged 15-34 years. But Dr. John Campo, chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health at Ohio State, said he sees this as preventable.

“Suicide from our perspective is absolutely preventable, and I don’t think there is any way to approach it without what I would call a ‘zero tolerance mindset.’ How many suicides a year is acceptable? From my perspective, it should be zero,” Campo said.

In 2013, there were 41,149 suicides in the United States, which equates to about 113 suicides each day, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Suicide Facts at a Glance 2015.

This problem hits close to home for some at OSU, as many college students experience large amounts of stress, which can be harmful to their mental health.

Within a representative year at OSU, “one in three students reported prolonged periods of depression” and “one in four students had suicidal thoughts or feelings,” Matthew Fullen, program manager of the OSU Suicide Prevention Program, said in an email.

Furthermore, about 7 percent of OSU students actively considered suicide. More than 1 percent attempted suicide — approximately 850 attempts, Fullen said.

Higgenbotham said simply talking about the subject could help those who are at risk of suicide get the care they need.

“The more I started talking about it, the more I realized that the more you talk about it the easier it becomes to talk about it,” she said. “Now I talk about it so much that it’s such a normal thing for me to talk about … I kind of try to engage a lot of my friends in conversations about it just to kind of show them that suicide is not that scary of a topic to talk about.”

Campo agreed that talking about suicide and mental health can be an effective way to show support and offer assistance.

“The important thing for all of us to know about suicide is that people who struggle with suicidal impulses, that that impulse, it can kind of come over (them) like a wave,” Campo said.

He added that it is helpful to understand how much of an impact access to resources can have on suicidal individuals during these overwhelming periods.

“The wave kind of crests and recedes, and a lot of times the most important thing is to have somebody who is compassionate and caring who can help that individual cope when they are at that time of maximum distress and then getting them to the good services that they deserve,” Campo said.

Mental health concerns for college students

There are a number of stresses on students that could lead to mental health issues.

“Students within university settings are under a huge amount of stress,” Campo said. “And it is sometimes academic stress, oftentimes it is relational stress.”

Campo said the stress of being an adolescent often has to do with balancing becoming your own person while staying “connected to the people that you love and who love you.”

Furthermore, the tendency of students to worry about invading each other’s privacy during the transitional life stage of college might dissuade them from asking each other about their mental well-being, Campo said.

“I think that one thing that I want to emphasize that I know young people struggle with is this whole issue of privacy and confidentiality,” he said. “What I would say to young people is I think they are often worried that, ‘Gee, my friend will be offended if I express my concern’ … I think that this is something that folks need to just confront, and sometimes there is a time for having some courage and this is what friends do. Friends have courage, and they have the courage to reach out and take risks, and that is what we need to do sometimes when somebody is really struggling.”

Higginbotham said serving as an active and empathetic listener is something that she learned her junior year, when she helped connect a friend who was having suicidal thoughts to campus resources.

“I was able to get him into (Counseling and Consultation Service) and after, you know, a couple months of that, he was feeling a million times better,” she said. “I was just really thankful that he was able to get help.”

College students versus nonstudents

Though college students are presumably under a great deal of stress, statistically they are not worse off than people of the same age range who are not enrolled in college.

“The absolute risk of suicide is greater for those young people who don’t attend university,” Campo said.

Although data from the CDC fact sheet showed similar percentages of full-time college students and other adults 18-22 years old having suicidal thoughts, there was a disparity when it came to actual attempts.

Full-time college students were less likely to attempt suicide compared to their nonstudent 18-22 year old counterparts. Full-time college students were also less likely to receive medical attention as a result of an attempted suicide compared to their nonstudent peers, according to the CDC fact sheet.

Campo said there are a variety of “underlying vulnerabilities” that contribute to an individual’s ultimate decision to complete suicide. He added that although stress can impact an individual’s mental health, other risk factors include pre-existing mental illnesses and addictions.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, more than 90 percent of people who complete suicide have been diagnosed with a mental illness. Additionally, substance abuse and addiction have been associated with increased risk of suicide, according to the NAMI Suicide Fact Sheet.

“Oftentimes what you see is if you look at completed suicides, more often than not, the individual who has completed suicide has been using alcohol or some other drug, which may lower inhibitions, which may make people more likely to act impulsively and in ways that they otherwise would not if they weren’t using a substance,” Campo said. “Suicide is a multidetermined, multifaceted problem, so all of these different things are important and related.”

Access to care

Campo said one of the biggest aspects of suicide recently studied by the Wexner Medical Center has been the impact access to care has on the suicide rates observed in young people.

In a study conducted by several researchers from the Wexner Medical Center published in JAMA pediatrics in March, Campo and Cynthia Fontanella, the lead author of the study, found that the youth suicide rate in rural areas was nearly double that of urban areas from 1996 to 2010. Campo said one of the reasons for this difference between rural and urban areas has to do with access to care.

“If you look at regions that have 24/7 crisis assessment services available, regions that have better access not just to mental health services but to primary care services in general, that better access to care does seem to be associated with reductions in the suicide rate,” he said. “So one of the issues is how do we improve services? … How do we make sure that those folks actually get the good care that they deserve?”

Campo said steps have been taken at OSU to provide access to services, and he added that he hopes further collaboration will occur between medical center resources and those offered by the university on campus.

“We have been working very closely with the counseling center here at Ohio State to bridge that transition. To make sure that folks connect to the good services that are available in our counseling center,” he said. “What I would like to see on our campus is really an integrated system of care for students, both undergraduate and graduate students, and faculty who struggle with emotional behavior or addiction-related problems … So what we see our role is, is being able to provide those higher levels of care in collaboration with our colleagues on campus.”

Higginbotham stressed the importance of having a support system when reaching out for care.

“A lot of times people have a hard time getting help on their own. Sometimes they just need someone go with them or just support them through it,” she said.

More information about suicide-related services is available at suicideprevention.osu.edu. The Franklin County Suicide Prevention Coalition hotline is 614-221-5445.

This series was made possible by the generosity of The Lantern and Ohio State alumna Patty Miller.