Sometimes ice cream and Netflix might not be enough to cure a bad mood — a new study suggests that people tend to search social networking sites such as Facebook to instead find people who are worse off in order to boost their own egos.

The study was conducted by Ohio State communication professor Silvia Knobloch-Westerwick and recent doctoral graduate in communication Benjamin Johnson. It was published online in the journal Computers in Human Behavior and is slated to be published in print in December.

“We were interested in how people might use social media to manage their moods,” Johnson said over Skype.

Johnson is now an assistant professor of media psychology at VU University Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

Johnson said they looked at a total of 168 OSU students, and the study was conducted over the course of several weeks.

Knobloch-Westerwick said the study came in two parts. In the first part of the study, participants were randomly assigned to either a negative or a positive mood.

“We had participants first take an alleged emotion recognition test,” Knobloch-Westerwick said, “which really served to place them into different emotional states.”

Depending on the assigned emotional state, participants would either get positive or negative feedback, even though the test did not actually gauge their ability to recognize emotions, Knobloch-Westerwick said.

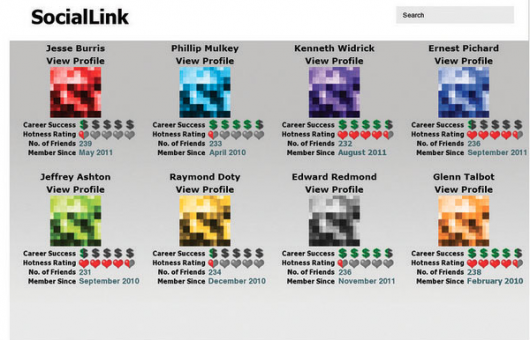

Johnson said in the second part of the study, participants were shown a mock social networking site.

The site, set up similarly to Facebook, featured eight profiles with generic, blurred profile pictures. Each profile was then rated on a scale of one dollar sign to five for “success” level, and on a scale of one heart to five for “hotness” level.

The participants were given two minutes to browse the profiles, which had only generic status updates unrelated to their “success” or “hotness” rating.

“And then we tracked their behavior,” Johnson said. “So we saw if they were more interested in particular kinds of upward comparisons or downward comparisons based on which (profiles) they looked at and for how long.”

Johnson said an upward comparison occurred when a participant spent time looking at a profile of a person “better off,” and a downward comparison occurred when looking at a profile of a person “worse off.”

“People generally preferred the profiles of successful people, but that also depended on their current mood state,” Knobloch-Westerwick said.

Participants in the negative mood category were more interested in downward comparisons, Johnson said.

According to the study, participants in a bad mood spent more time visiting the profiles of people who were rated unattractive and had low career success.

“We believe that that’s because they used that to make themselves look better by comparison,” Johnson said. “People look to other people in their social environment to regulate their own sense of self, their sense of well-being, and their emotion.”

Some students have validated the results of the study with their social media habits while others perhaps bring the findings into question.

Jessica Brock, a fourth-year in respiratory therapy, said she usually checks Facebook to boost her mood when she’s feeling blue. She said looking at unattractive people’s profiles sometimes helps her feel better about herself.

“I actually have contacts on social media for that sole purpose,” Brock said.

She said looking at said posts make her feel more down while more uplifting posts make her happy.

Alex Myers, a third-year in anthropology, said while he doesn’t seek out social media to change his mood, sometimes the social media he consumes ends up doing so.

“I check more current events, 80 percent of the news is negative so … when I look at things from Canton, Ohio, where I am from there is a lot of crime going on,” he said. “I kind of reflect on that, so my mood is negatively affected. I don’t think I use it to actively influence my mood though.”

Myers also said he’s never really noticed feeling better when in a down mood after looking at an unattractive person’s profile or an unfortunate status update.

Still, Knobloch-Westerwick said she’s convinced otherwise.

“People try to boost their egos,” Knobloch-Westerwick said. “Everyone does it.”

Jeremy Savitz contributed to this story.