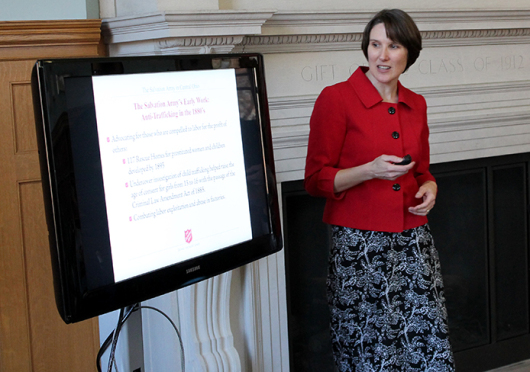

Michelle Hannan, director of professional and community services for the Salvation Army of Central Ohio, speaks to a crowd of OSU students and faculty about human trafficking Feb. 10 at Thompson Library. Credit: AJ King / Lantern photographer

President Abraham Lincoln abolished slavery in the 1860s, but it wasn’t until about 140 years later that the federal government criminalized another form of slavery, human trafficking.

Human trafficking was the topic of discussion at the first of four lectures in a series called “Tuesdays @ Thompson,” hosted at Thompson Library.

Tuesday’s speaker was Michelle Hannan, the director of professional and community services for the Salvation Army of Central Ohio.

“What has happened with human trafficking, with the absence of the law saying it’s OK to own someone and benefit from their labor, other ways of keeping people enslaved have developed,” Hannan said in her presentation speech. “The good news about the year 2000 was the Trafficking Victims Protection Act passed, and it gave us a federal criminal definition of (human trafficking).”

Hannan added that the act is centered on three main goals: Prevention, protection and prosecution.

“When it first passed in 2000, there was a real emphasis on overseas because the goal was to prevent trafficking overseas,” Hannan said. “And that’s all true, but since 2000, slowly through the first decade, the U.S. finally started to grasp that it’s not just an issue happening overseas, it’s not just about trapping people in the U.S. either. That in fact, American citizens are being trapped here stateside. And honestly, I think it took us a little while to open our eyes to that because it’s a pretty ugly reality.”

The issue can hit closer to home for Ohio State students as well. In her presentation, Hannan provided vignettes illustrating different cases of human trafficking in Central Ohio.

Hannan shared a story about a woman with cognitive disabilities and her child being held captive in the home of her traffickers in Ashland, Ohio, a city approximately 80 miles northeast of Columbus. They were allegedly forced to perform manual labor and were subjected to rape and extreme brutality, Hannan said.

“This case is an ugly example of the brutality human traffickers use because they were treated like dogs in a lot of ways,” she said. “They were forced to wear collars and forced to eat food from a bowl on the ground. These techniques are used to break them down, so they won’t get help.”

In another instance, a 15-year-old girl from a troubled home in Delaware County, which is to the north of Franklin County, ran away to escape abuse, Hannan said. She was “befriended” by a trafficker who pretended to love and care for her, but who then allegedly forced her into prostitution for his profit, Hannan added.

“Once she is intensely bonded to him, he starts selling her for sex in Central Ohio,” Hannan said. “Here we have a young person whose vulnerability is that it’s not safe at home.”

On another occasion, David Nelms of Columbus allegedly forced opiate-addicted women into sex trafficking, catering to paying customers at upscale hotels in Franklin and Delaware counties, Hannan said. She said Nelms used victims’ drug addictions to compel their obedience by withholding drugs until they complied with his demands.

“If you know a lot about opiate withdrawal, if you’re addicted to opiates and you suddenly don’t have them, your body’s response to that is to feel like you’re going to die,” Hannan said. “It’s the best control technique ever invented.”

Many of the victims of human trafficking are afraid to seek help, Hannan added.

“Because there is inherent criminal activity in what people are forced to do, the traffickers use that to scare them into not getting help,” she said.

In her presentation, Hannan also said that the Salvation Army provides numerous resources designed to help victims of human trafficking.

“We play a part in continual care. We coordinate the 24-hour human trafficking hotline on behalf of the whole Central Ohio area,” she said. “Within that continual care, we are the primary victim advocate for law enforcement, so our person is there with them to immediately start to figure out their needs and assist them.”

Hannan said the Central Ohio Salvation Army has been conducting street outreach in order to protect those impacted by human trafficking in Columbus and other cities.

“It starts to build connections and relationships and say, ‘Hey! Here’s our hotline card, here’s a bag of healthier products, snacks and if you need anything let us know,’” she said.

For some students attending the event, the proximity of human trafficking was shocking.

“l didn’t realize human trafficking was going on here,” said Meghan Esarove, a second-year in health sciences. “I always thought it was just stuff that happened in the movies. It’s definitely important to spread awareness.”