Beyond the box:

How formerly incarcerated Buckeyes navigate college

When Amber Michael was released from her three-and-a-half-year stint at the Ohio Reformatory for Women, she had few possessions to her name.

No driver’s license, no birth certificate, no phone, no way to verify her identity. Just a $65 check she couldn’t cash, a ride to the Greyhound station and a three-year parole sentence.

Michael, now a graduate student in the College of Social Work at Ohio State, was 20 years old and in the “full swing of addiction” in July 1998 when she pled guilty to the aggravated robbery of a grocery store with a codefendant firing shots at police in a 90-mph chase.

Although she accepted full responsibility for the crime, there’s one thing Michael said she cannot accept: the fact that her conviction has followed her like a shadow even 20 years after her release from prison.

“I did not know that the decision I was making, that I would carry it with me for the rest of my life,” she said. “I wasn’t capable of understanding that.”

About 70 million Americans — or 1 in 3 adults — have been involved in the criminal justice system through an arrest or conviction, according to a 2016 report from the U.S. Department of Education.

Of those individuals, about 600,000 reenter society each year, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Many, like Michael, are required to indicate their past criminal record — or “check the box” — when asked a series of questions on applications or conditions upon acceptance to employment, housing and higher education, including Ohio State.

It’s not clear how many admitted Ohio State students have checked the box in past years, but only 20 out of 217 students who checked the box were denied enrollment to the university for the 2019-2020 school year, the most recent data available.

The university’s intention in requiring students to disclose their criminal or disciplinary background is to provide “a safe living, learning and working environment” for the Ohio State community, according to a university enrollment services website.

Maeve Walsh reported this story in her position as The Lantern’s John R. Oller Special Projects Editor. Oller’s generous endowment, like others, supports The Lantern’s mission to independent, investigative reporting. Consider supporting our work by donating here.

Although checking the box does not automatically bar enrollment, critics of the requirement, including Tiyi Morris, associate professor of African American and African Studies at Ohio State, argue that the box deters people with a past conviction or disciplinary offense from applying to the university.

Morris, who teaches joint classes of incarcerated and non-incarcerated students in the university’s Inside-Out Program, said some people refuse to apply to Ohio State out of fear of being denied, or because the requirement to explain one’s situation as a condition upon enrollment may be too traumatic.

“It simply is an additional barrier right after you’ve been released; it inhibits people’s ability to fully, really integrate into society, and education has been shown proven to be a significant factor in reducing recidivism,” Morris said.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, nearly two-thirds of people with a felony conviction stopped a college application once they were asked about their involvement with the criminal justice system, a study by the State University of New York found.

In 2017, Ohio State and several other universities eliminated the criminal history question from their applications — which was first asked by the university in the ’90s — amid encouragement from the U.S. Department of Education and a growing “Ban the Box” movement.

“[Students] literally will go through the entire application process and not know that that question is asked at any point prior to them receiving admission to the university,” a representative from university admissions said. “And that was intentional, for the very reason of kind of mitigating the chilling effect.”

However, as part of the acceptance fee process, Ohio State requires accepted students to answer a community enrollment question — indicating whether the student has a prior or pending disciplinary action or felony conviction — as a condition for enrollment to the university, according to the university enrollment services website.

Ivan Kostovski | Infographics Editor

Beth Wiser, executive director of undergraduate admissions, said unlike competitive admissions at Ohio State, there is no limit to how many students the university can grant enrollment. Each case is reviewed individually while taking into account the unique experiences and circumstances of each student, Wiser said.

“It really is designed to be a process that we’re looking for reasons to say, ‘Yes, we admitted these students; we want them to be Ohio State students.’ So we’re going in with that particular philosophy,” Wiser said.

Others say this requirement harms marginalized populations’ access to higher education, while making campus no safer than universities who do not require a disclosure of criminal history. Those who are granted enrollment by the committee still encounter challenges outside of the realm of education, including access to employment and housing.

Deanna Mascia, now a graduate student in the College of Social Work, said she can’t help but feel anxious when it’s time to “check the box” on various applications or questionnaires.

“It’s also like a 50/50 throw-up — if you’re going to get judged or if you’re going to get a second chance,” Mascia said.

Prior to enrolling at Ohio State, Mascia played soccer at Ohio Dominican University, a private Catholic college in Columbus. Although Mascia said she drank “intermittently” in the first few semesters of college, it wasn’t until her soccer coach dismissed her from the team when she came out as gay that her “active addiction” began to develop.

“I don’t want to say it was the cause of [my addiction] because I did have the tendency, but it definitely, it definitely kick started the inevitable,” Mascia said.

Shortly after being kicked off the team, Mascia was pulled over by a police officer in 2013 and convicted of driving under the influence. She was 19 years old; it was her sophomore year in college. Eventually, she failed out of Ohio Dominican, she said.

Her jail time was deferred on the condition that Mascia adhere to a few guidelines and sanctions — including what she calls “drunk camp,” a three-day hotel stay where she and other participants were instructed on how to not drink and drive, she said.

“I didn’t do all the things they (the judge) asked, but they never found out,” she said. “I even drank and smoked weed at that place.”

Still grappling with addiction three years after the DUI, Mascia applied as a part-time student to Ohio State in 2016, which was put on a brief hold when she entered a program at Columbus Springs, a mental health and addiction treatment center in Dublin, Ohio, during the 2016-17 school year. Mascia said she’s been sober since 2017.

Although Mascia said she was accustomed to disclosing her prior criminal record, the “nerve-racking feeling” of being denied persisted when she applied to Ohio State.

“It feels like you’re bringing up something from your past that you’re trying to get over that you just can’t,” Mascia said

Beth Wiser, executive director of undergraduate admissions, said unlike competitive admissions at Ohio State, there is no limit to how many students the university can grant enrollment. Each case is reviewed individually while taking into account the unique experiences and circumstances of each student, Wiser said.

“It really is designed to be a process that we’re looking for reasons to say, ‘Yes, we admitted these students; we want them to be Ohio State students.’ So we’re going in with that particular philosophy,” Wiser said.

Others say this requirement harms marginalized populations’ access to higher education, while making campus no safer than universities who do not require a disclosure of criminal history. Those who are granted enrollment by the committee still encounter challenges outside of the realm of education, including access to employment and housing.

Deanna Mascia, now a graduate student in the College of Social Work, said she can’t help but feel anxious when it’s time to “check the box” on various applications or questionnaires.

“It’s also like a 50/50 throw-up — if you’re going to get judged or if you’re going to get a second chance,” Mascia said.

Prior to enrolling at Ohio State, Mascia played soccer at Ohio Dominican University, a private Catholic college in Columbus. Although Mascia said she drank “intermittently” in the first few semesters of college, it wasn’t until her soccer coach dismissed her from the team when she came out as gay that her “active addiction” began to develop.

“I don’t want to say it was the cause of [my addiction] because I did have the tendency, but it definitely, it definitely kick started the inevitable,” Mascia said.

Shortly after being kicked off the team, Mascia was pulled over by a police officer in 2013 and convicted of driving under the influence. She was 19 years old; it was her sophomore year in college. Eventually, she failed out of Ohio Dominican, she said.

Her jail time was deferred on the condition that Mascia adhere to a few guidelines and sanctions — including what she calls “drunk camp,” a three-day hotel stay where she and other participants were instructed on how to not drink and drive, she said.

“I didn’t do all the things they (the judge) asked, but they never found out,” she said. “I even drank and smoked weed at that place.”

Still grappling with addiction three years after the DUI, Mascia applied as a part-time student to Ohio State in 2016, which was put on a brief hold when she entered a program at Columbus Springs, a mental health and addiction treatment center in Dublin, Ohio, during the 2016-17 school year. Mascia said she’s been sober since 2017.

Although Mascia said she was accustomed to disclosing her prior criminal record, the “nerve-racking feeling” of being denied persisted when she applied to Ohio State.

“It feels like you’re bringing up something from your past that you’re trying to get over that you just can’t,” Mascia said

Deanna Mascia, now a graduate student in the College of Social Work, was convicted of driving under the influence in 2013 when she was 19 years old. Mascia, who has been sober since 2017, said disclosing her criminal background as a condition upon enrollment to Ohio State was a “nerve-racking” process — she wasn’t sure whether she would be judged for her past or be given a second chance.

Mackenzie Shanklin | Photo Editor

If a student answers “yes” to the community enrollment question, their enrollment to Ohio State is put on hold, and they are required to write a personal statement describing the offense in full, any rehabilitative efforts the student has undertaken and what they learned from the experience.

“We really want admitted students to be reflective of their experience as both the criminal as well as educational, disciplinary, and it allows students to really share voice about their experience and what they took away from it,” a representative from university admissions said. “It is endemic to higher education.”

The University Community Enrollment Review Committee, composed of representatives from various Ohio State offices and departments, then reviews the documentation to determine whether the student will be able to enroll at the university, according to the committee’s website.

The committee also consults with past schools where a student may have received a disciplinary action and if applicable, any individuals who may be assisting a student with the transition from their past criminal or disciplinary action, Wiser said.

“Every case is looked at individually,” Wiser said. “That’s why we make those contacts and take the time to talk to the other schools so that we’re not predetermining any outcome for a student.”

The entire review process takes about four to six weeks once the student’s documentation is submitted, according to the committee’s website. The majority vote determines the student’s outcome, and students are notified of the committee’s decision via email, the committee representative said. Students are not permitted to appeal the decision.

During the 2019-2020 school year, a total of 217 admitted Ohio State students answered affirmatively to the community enrollment question, according to the committee’s annual summary report.

However, 95 of those responses were deemed “error responses,” which occurs when a student either accidentally checks yes to the question or mistakes their high school gym suspension as rising to the level of criminality or disciplinary action requested by the committee.

The 95 error responses, along with 72 other responses, were first reviewed and cleared — or granted enrollment — by a separate entity, the Academic Relations Competitive Admissions and Access and Diversity committee, which serves as a precursor to the committee in order to review files that don’t rise to the level of the committee’s purview, university spokesperson Ben Johnson said in an email.

“These are primarily academic offenses like detentions, suspensions and other infractions,” Johnson said. “ARCAAD may also review misdemeanor offenses that are not associated with a felony.”

After accounting for the files reviewed by ARCAAD, the committee was left with a total of 50 files to review for the 2019-2020 school year. Of those 50 files, the committee cleared 30, which included 23 felony convictions and seven disciplinary actions, according to the committee’s annual report.

A total of 20 files were not cleared by the committee — in other words, denied enrollment to the university. Among those, two were felony convictions and 18 were disciplinary actions.

The Lantern was unable to access committee enrollment data from previous years, since the university’s elimination of the box from the application in 2017, and other amendments to the committee’s policies, don’t allow for data points that can be compared over time, Johnson said.

Although Michael’s files were ultimately cleared, granting her enrollment to the university when she applied in 2017, she said checking the box makes her question her place at Ohio State, and whether her colleagues and classmates perceive her as an equal.

“Twenty years later, I’m a mother, I’m a grandmother, I’m a college graduate twice. I work in the community, I volunteer, do all kinds of things,” Michael said. “And people still want me to say what I did, what happened as a result of that, how I was punished and what I learned from that punishment, including this institution.”

The “scarlet” box

After Michael was released from the Ohio Reformatory for Women, Ohio State was not the only institution that required her to disclose her status as a convicted felon. The box, Michael said, is like “this scarlet letter.”

“The higher up the ladder that I tried to climb, the more I ran into that box,” she said.

Michael said she struggled to find housing that would accept her with her background, and to this day, she is unable to sign for an apartment or house under her name because of the nature of the crime.

The only apartment complex that accepted Michael’s housing application in 2000 was 31 Chittenden Ave., a three-story brick building with white columns in the front that sits just a few steps east of High Street.

Amber Michael stands in front of her old apartment complex located at 31 Chittenden Ave.

Christian Harsa | Asst. Photo Editor

“I couldn’t get an apartment to save my life,” Michael said. “I stayed in a gross little slum when I first came home from prison that had roaches and rats.”

Finances were also an issue out of prison, Michael said. Despite earning $21 a month working as a literacy tutor at the Ohio Reformatory for Women for other incarcerated individuals — constituting her as one of the “higher paid inmates” — she hardly had enough money to afford basic necessities upon release.

Finding gainful employment often required Michael to disclose her criminal background, and when interviewing for her first job out of prison, she was met with an apprehensive facial expression — which she calls “the look” — from the man reviewing the section on her application where she disclosed the felony conviction.

Ultimately, Michael said she didn’t get the job.

“I avoided any job situation where I might have to contend with that. I stayed in jobs that I knew did not care, they didn’t care,” Michael said. “They just needed me there, you know, unattractive jobs, food service, manual labor cleaning, those kinds of things, because nobody wants to do those jobs.”

Mascia, who had to check the box on job applications, for her driver’s license and for her master’s program, compared the anxiety behind answering affirmatively to the community enrollment question to the uncertainty associated with disclosing her sexuality on applications.

“There’s a box that you fill out when you apply places, like if you identify as (part of the) LGBT community, and I still don’t want to do that because I faced a lot of backlash when I came out for years,” Mascia said.

Another concern that Mascia and other proponents of the Ban the Box movement have is the fact that marginalized populations are more likely to suffer from disclosing one’s criminal history as a condition upon enrollment to the university.

Mary Thomas, an associate professor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies at Ohio State who teaches joint classes of incarcerated and non-incarcerated students in the Inside-Out Program, said that children with disabilities and those in the LGBTQ+ community — like Mascia — are more likely to be disciplined in school or by police, and thus are more likely to be denied enrollment to the university.

“Kids who are queer and engage in sexual activity underage are much more likely to be policed or arrested or suspended for same-sex practices, too, so queer kids are over-represented,” Thomas said.

The box also has racial implications, Thomas said, as Black people are disproportionately apprehended, arrested and convicted by law enforcement in the U.S.

Black people made up 44.8 percent of the incarcerated population within the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction in 2019, according to ODRC’s annual report, despite accounting for only 13 percent of the state’s total population, according to the U.S. Census.

Not only are Black people disproportionately arrested or convicted with a crime, but Mascia said her privilege as a white woman also contributed to the treatment she received from members of law enforcement during the time of her arrest. She never felt afraid at any point during the encounter — something she said would likely not be the case for a person of color.

“I was driving a three-ton weapon at innocent people who’d never never asked for someone to put their life in danger on the road,” Mascia said. “And the officer was pretty polite.”

Wiser said she recognizes there are “a lot of different chilling effects” for historically underserved and disenfranchised populations when it comes to access to higher education, and Ohio State will continue to adapt its policies to adhere to the university’s values.

“Ohio State continues to evolve in understanding and taking a look at our policies to ensure that we can carry out that mission knowing that education has a lot of redemptive qualities to it, and to be able to help make Ohio State possible for students,” Wiser said.

Johnson said the university is committed to creating an environment and adopting policies that are not only open and equitable, but also anti-racist.

“We’ve seen an increase in this really important conversation about the balance between public safety, and the very real need to ensure equity and fair treatment and justice,” Johnson said. “And we want not just to be part of that conversation, but to be a leader in that conversation.

The Ohio Prison Education Exchange Project, an organization created by Morris and Thomas in 2020, seeks to increase incarcerated students’ access to higher education and eliminate some of the damaging effects of the box. OPEEP also offers an Inside-Out program at the university, where classes are held inside a prison, composed of both students incarcerated and those who are not.

Michael enrolled in one of the Inside-Out classes at Ohio State while in undergrad, and she said it was a transforming experience as a formerly incarcerated person.

“I was probably closer to the inside students than I was to the outside because you just have a different — we have a similar understanding,” she said.

Morris and Thomas said the support of their program’s efforts by Ohio State administrative offices has been “remarkable,” and one of their ultimate goals is to provide incarcerated students with opportunities they may never have perceived to be possible.

“For many students, that again boosts their self esteem and their confidence and lets them know that they are able to access and participate fully in the higher education experience,” Morris said. “And that that is a viable option for them upon their release.”

The UCERC Committee and Review Process

Once the U.S. Department of Education delivered recommendations regarding universities’ requirement to disclose criminal background, Ohio State and other Big 10 universities began to eliminate the box from the application process.

Among the recommendations provided by the U.S. Department of Education included the fact that “colleges and universities that admit students with a criminal justice history have no greater crime than those that do not,” according to the department’s 2016 report.

Thomas said the argument made by the university that the community enrollment question serves to promote the safety of the campus community is simply to maintain a false semblance of safety at the university.

“Here we have another committee, right, that has this facade of fairness, but in practice, it’s very cloaked in mystery,” Thomas said.

Proponents of Ban the Box argue that a lack of transparency characterizes the committee’s review process, as the names of individuals that sit on the committee is not public information, and reasons why a student is or is not permitted enrollment to Ohio State are not provided.

The offices and departments represented by members of the committee are, however, provided on its website, including the following:

- Office of Student Conduct

- Office of Legal Affairs

- Office of Institutional Equity

- Counseling and Consultation Services

- University Housing

- Department of Public Safety

- Undergraduate Admissions

- The Graduate School

A committee representative said that committee members have conversations surrounding implicit bias and other training programs that allow them to take into consideration a student’s holistic experiences. Members of the committee are chosen based on what they can bring to the table to support students, he said.

“We focus on the unique skill sets that each member brings to understanding students first and foremost, and where students are in their cognitive development, and why that’s important to factor in,” the representative said.

Among the departments involved in the committee, Wiser said Counseling and Consultation Services is particularly important in offering a lens into behaviors influenced by trauma or other circumstances in a student’s life at the time of the crime.

“Those that are so focused on fairness and equity issues, and things that go beyond just academic success of a student, you know, their voices are key in the decision making process,” Wiser said.

The requirement for students to disclose any rehabilitative measures they’ve taken and how the experience has changed them may create problems for students who are not provided advice or “are struggling on their own to figure out the system,” Thomas said.

Those students may be at a disadvantage when it comes to advocating for themselves on the disclosure form — and often may force the student to convey remorse for a situation characterized by their own mental health problems or injustice perpetrated by an authority figure, Thomas said.

“You have to perform this regret in order for them to even recognize you as redeemable,” Thomas said. “And I think that also just completely abstracts an individual from the sorts of gross injustices in our society.”

Michael said that when she crafted a statement regarding rehabilitative measures and how she has grown from the experience, she essentially gave the committee the ability to determine her value as a human.

“We might take it to look over you, as a human being on these three paragraphs that we assign to you and decide whether or not you’re worthy or unworthy, because that’s what it boils down to, for me. It boils down to worth,” Michael said.

Despite guidance from the U.S. Department of Education, Wiser said it takes time before the university can see changes in patterns of success or safety once major policy changes are initiated.

“We want to make sure change obviously happens a policy at a time, but not wanting to lose sight that there are additional issues that we continue to try to address every day as Ohio State to make sure that we’re not putting barriers in front of students who are ready and prepared for the educational opportunities that Ohio State provides,” Wiser said.

Some proponents of Ban the Box think convicted felons and those with prior disciplinary actions are a scapegoat, and the university’s concern with maintaining safety is directed toward the wrong people.

Thomas said that students on campus — particularly in relation to sexual violence on campus — are much more likely to be the victim of crime by someone they know, not a convicted felon released from prison years ago.

“This idea that we can’t let people convicted of felonies in because they may hurt our white girls, when in fact, you’re at much greater risk — all white women, and all women actually, are at much greater risk — of any kind of assault by people they know,” she said.

Thomas said the notion of public safety is rooted in a desire to protect white students, which comes at the expense of suppressing the opportunities, available to formerly incarcerated people, who represent historically marginalized groups.

“When I see that word, like ‘public safety’ or ‘your safety,’ it’s really white people’s safety,” Thomas said. “It’s the suburban white students’ safety the university prioritizes.”

From what Michael has seen in her experience, she said the majority of crime that happens on Ohio State’s campus is perpetrated by people who don’t live on campus and don’t even attend the university.

Yet, perpetrators of crime on campus, especially those committing sexual violence, are not subject to the committee’s scrutiny, Michael said.

“I can spot her (a female student’s) abuser one million miles away, and I guarantee you he did not get sat down by UCERC, I guarantee it,” she said. “You know, he’ll probably be president one day.”

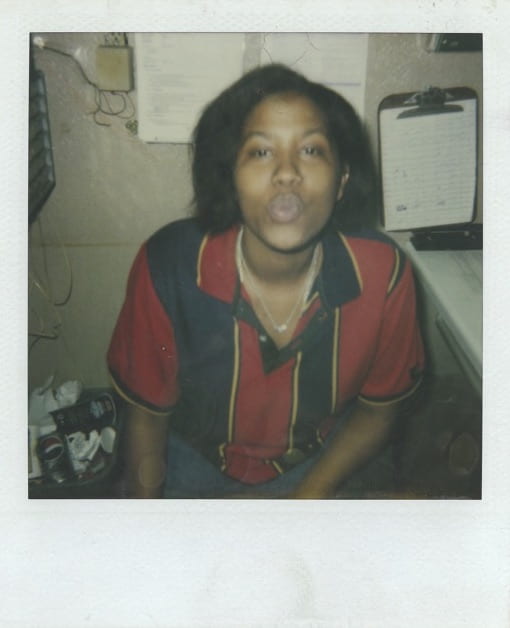

Photo Caption: Amber Michael, left, stands with her mother while incarcerated at the Ohio Reformatory for Women in Marysville, Ohio. Michael, now a graduate student in the College of Social Work, a mother of two and a grandmother, said her past conviction has followed her for the entirety of her life. Courtesy of Amber Michael

Now, as a mother of two and a grandmother, Michael has been sober for nine years, and she said it’s strange to reminisce on her time in prison.

“I don’t know that girl anymore,” she said. “It’s odd to try and reach back for it.”

Web Design by

Jack Long | Managing Editor for Digital Content

Support The Lantern

The Lantern is the award-winning, independent student voice of Ohio State. Please consider supporting the future of journalism by donating to The Lantern.